Summary

Trade and tariffs have been a dominant theme in 2025, and 2026 could bring more of the same as the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) is renegotiated. In this piece, the Beutel Goodman Fixed Income team looks at the importance of this deal for Canada and how negotiations could play out in the months ahead.

By Beutel Goodman Fixed Income Team

The trade relationship between Canada and the United States has a long and fruitful history. So long in fact, that it predates Canadian Confederation and stretches back to the aftermath of the American Revolution and the signing of the Jay Treaty in 1794. Since then, trade between the two neighbours has been upended by different periods of protectionism, most notably after the American Civil War (1861–1865), but the countries have largely embraced free trade since around 1935.

This stance was codified with the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994 and its successor, the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) in 2020. USMCA covers important cross-border spheres such as autos, digital trade, labour and the environment, and is scheduled for renewal in 2026, which could have far-reaching consequences for the Canada-U.S. trade relationship.

Strong Ties on Trade

Earlier this year, the U.S. administration announced tariffs on its international partners, and since then, trade has become a dominant theme. That’s particularly the case in Canada where the economy is so deeply intertwined with the United States. In 2024, the U.S. was the destination for 76% of Canada’s goods exports, with approximately 17% of U.S. goods exports moving in the opposite direction (source: Statistics Canada).

An export economy blessed with an abundance of natural resources, Canada’s main exports to the U.S. include energy (29%); metals and minerals (9.1%) such as steel, aluminum, copper; consumer goods (12%) such as pharmaceuticals and food; industrial inputs including machinery and chemical products (12.4%); as well as lumber & forestry products (6.8%). In addition, autos account for 13% of Canadian exports and are a vital part of Ontario’s economy (source: Statistics Canada). The auto industry is also a prime example of the how integrated supply chains have become since the signing of NAFTA in the 1990s — according to the Canadian Vehicle Manufacturer’s Association, autos produced in Canada contain around 50% U.S. parts. In fact, roughly 59% of U.S. goods imports from Canada are classified as intermediate inputs (source: Office of the Chief Economist, Global Affairs Canada).

This integration in supply chains and economies is also evident by the composition of U.S. exports into Canada. Canada’s imports from the U.S. are largely comprised of manufactured goods that are often made with Canadian raw materials, including autos and auto parts (22%); consumer goods (15%), industrial products including machinery and chemical products (22%), and materials made from forestry products (6.2%) (source: Statistics Canada).

Tariff Talk

The Canada-U.S. relationship has been strained this year, with baseline 35% tariffs (enacted through the IEEPA: International Emergency Economic Powers Act) and targeted sector tariffs (enacted through Section 232 of the U.S. Trade Expansion Act of 1962) on imports of steel, aluminum and copper (50%); autos and trucks (25%); softwood lumber (45%); and select furniture (25%).

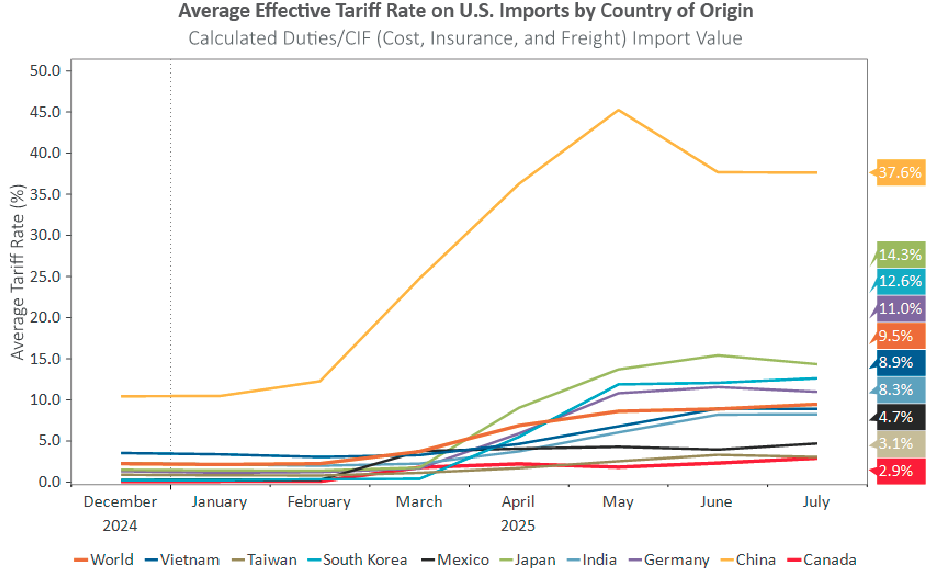

However, in reality, our average effective tariff rate is much lower, at approximately 5%. In fact, Canada has the lowest effective tariff rate for any trading partner of the United States (see Exhibit 1). This is largely down to the provisions of the USMCA which offer tariff exemptions on compliant goods. Even with newly threatened tariffs, the effective tariff rate is expected to rise to only about 6% in the coming months.

USMCA-compliance has risen markedly in the past year as businesses filled in the necessary country-of-origin paperwork. According to the Bank of Canada’s assumptions in its October Monetary Policy Report, 100% of Canadian energy exports and 95% of other exports are USMCA compliant.

Exhibit 1. Average Effective Tariff Rates on U.S. Imports by Country of Origin. As of July 2025, Canada has the lowest Tariff Rate on U.S. exports at 2.9%. The total world average is shown, along with the top exporters to the U.S. (Vietnam, Taiwan, South Korea, Mexico, Japan, India, Germany and China). All regions have tariff rates well above the rate on Canada, with China having the highest average tariff rate of 37.6%.

As of July 2025

Source: Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd., United States International Trade Commission (USITC)

Provincial and Sector Breakdowns

Another important factor to consider is the contrasting regional economies of Canada’s provinces — Alberta is the energy heartland of the country, British Columbia is most associated with the lumber trade and in Ontario, the auto industry is king.

Since the introduction of tariffs by the U.S. government this year, Ontario and Quebec appear to have been the hardest hit as they both have the highest percentage of exports exposed to tariffs as a percentage of GDP, as well as the highest average effective tariff rates (source: Statistics Canada). Quebec is also likely to be the most at risk from new sectoral tariffs that came into effect on November 1, largely due to new levies on heavy trucks. Meanwhile, BC, which was expected to be more insulated against the effects of tariffs, is now more exposed due to the U.S. Trade Expansion Act’s new Section 232 tariffs on softwood lumber.

Economic Headwinds

Although compliance with the USMCA has lowered Canada’s overall average effective tariff rate, the new trade environment has also coincided with a notable slowdown in economic activity. Exports into the U.S. have declined sharply since 2024, with the steel, aluminum and forestry sectors hit hardest.

However, as highlighted in the Bank of Canada’s latest Business Outlook Survey, it is not the tariff rates themselves but rather uncertainty over future U.S. trade policy that appears to be exerting the greatest pressure on the Canadian economy and labour market. Canadian businesses are responding in various ways, including seeking the cover offered by USMCA, as evidenced by higher compliance rates.

Maintaining the core provisions of USMCA will therefore remain a key objective for the Canadian government. That said, trade talks are unlikely to be straightforward — U.S. Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick recently remarked, “I think the president is absolutely going to renegotiate USMCA.”

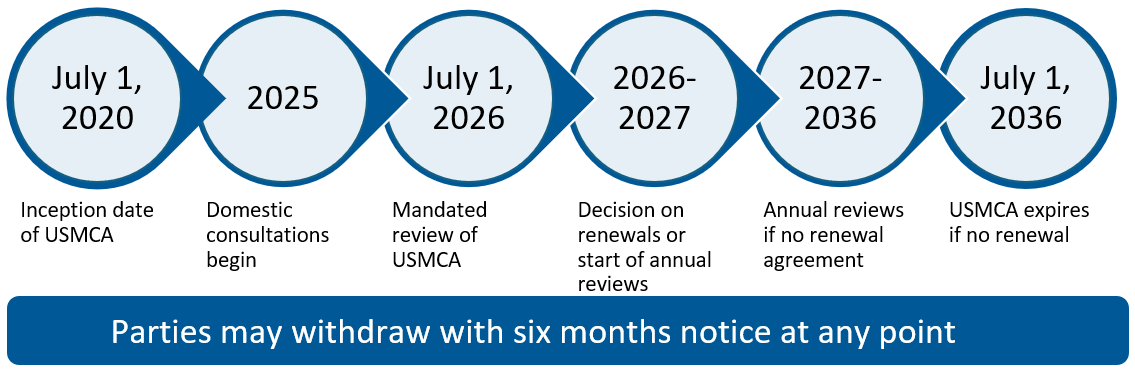

Looking at the existing agreement, there are three mechanisms in USMCA that could drive headline risk in the upcoming months, which are:

- Article 34.3: Amendments: Parties can amend the agreement at anytime at 60 days’ notice, possibly without a new congressional approval process if it doesn’t conflict with existing U.S. law.

- Article 34.6: Withdrawal: Any party can exit the agreement with six months’ notice, regardless of the review process. The agreement would continue between the remaining two parties.

- Article 34.7: Review and Term Extension: The USMCA requires a joint USMCA review every six years, beginning July 1, 2026. After each review, the U.S., Mexico, and Canada must decide whether to extend the agreement for another 16 years. If they cannot agree, annual reviews continue for up to 10 years (until 2036), at which point the USMCA would expire if no extension is reached.

Exhibit 2: Timeline of the USMCA Review Process. July 1, 2020: Inception date of USMCA; 2025: Domestic consultations begin; July 1, 2026: Mandated review of USMCA; 2026-2027: Decision on renewals or start of annual reviews; 2027-2036: Annual reviews if no renewal agreement; July 1, 2036 USMCA expires if no renewal; Parties may withdraw with six months’ notice at any point.

Renegotiation Scenarios

There is still much unknown as to how the review will progress. There is additional grey area as the USMCA text does not establish what parts of the agreement qualify as part of the review process (which would not require congressional approval) versus those that constitute a more substantive renegotiation (which requires congressional approval).

We therefore have identified three possible scenarios for how the renegotiation may play out.

Scenario 1: Straightforward Renewal of the Agreement (low disruption): If the 2026 review ends in a modest package and a 16-year extension, policy uncertainty should be reduced, which in turn supports capex and preserves economic integration, especially in autos/EVs and cross-border manufacturing.

Scenario 2: Contentious Renegotiation (high disruption): In this scenario, President Trump could issue threats of employing Article 34.6 Withdrawal and demand significant concessions, such as with autos rules, dairy, or government procurement. Talks could therefore drag, deferring investment and inviting brinkmanship. A contentious renegotiation could potentially result in further punitive tariffs on select industries (steel/aluminum, trucks, pharma, consumer goods) and destabilize integrated supply chains as tensions mount.

Scenario 3: Lingering Uncertainty (medium disruption): The deal keeps running but faces annual reviews and a 2036 expiry unless extended. Since renegotiation would require congressional approval, side deals are done in lieu of renegotiation and talks drag out in a proverbial “kick the can down the road” outcome. This would prolong the uncertainty that has already damaged the Canadian economy, resulting in slower business investment, delayed hiring, and precipitate a gradual unwinding of integrated supply chains.

In our assessment, Scenario 1 — Straightforward Renewal of the Agreement — appears highly unlikely. We also assign a low probability to Scenario 3 — Lingering Uncertainty — given the U.S. administration’s preference for securing trade deals rather than allowing prolonged ambiguity. This preference for certainty also aligns with Canada’s interest in greater policy clarity as the Build Canada budget initiatives move forward.

Instead, we expect negotiations to initially follow the pattern of Scenario 2 — Contentious Renegotiation — with hardline rhetoric and even threats of withdrawal dominating the discussion through the first half of 2026. Over time, we anticipate a period of turbulent trade talks culminating in a deal.

While we acknowledge the difficulty of forecasting U.S. trade policy — particularly amid this year’s tariff volatility — we believe the Canadian bond market is underpricing the risk that 2026 renegotiations will prove contentious for Canada in the first half of 2026. Our base case remains that there is potential for Canada’s effective tariff rate becoming more broad-based and rises to roughly 7–8%.

We also do not foresee the U.S. Supreme Court challenge of the IEEPA tariffs as having the potential to meaningfully improve our average effective rate, though it could lessen the uncertainty around the USMCA renegotiation.

Broad-based tariffs were enacted by the U.S. administration (such as those on Liberation Day) by citing the cross-border trade of fentanyl and trade deficits as national emergencies that needed to be addressed under the IEEPA. Using the IEEPA in this way is currently being challenged before the Supreme Court, because under the U.S. Constitution, only Congress has the power to introduce broad-based tariffs on countries or trading blocs. At this point, however, the IEEPA tariffs on Canadian imports are largely under the cover of USMCA, therefore a ruling either way would have limited impact on our average tariff rate.

In addition, if the courts rule against the president, the ruling would not challenge his authority to introduce targeted sector-level tariffs under section 232, therefore these industry specific duties could still increase. We would also likely see a push for congressional approval of broad-based tariffs, therefore USMCA renegotiations will still be a vital part of the trade relations.

Striking a Balance

In his first year as prime minister, Mark Carney will need to strike a careful balance in negotiating with the United States to help Canada’s economy navigate the threat of tariffs. On one hand, Canada must operate within the U.S. sphere of influence as Canada’s largest trading partner; on the other, Canada will need to guard against excessive dependence on that sphere, pursuing diversification of Canada’s economy both at home and abroad.

Operating within the U.S. sphere of influence

To strengthen Canada’s position within the U.S. economic sphere, the country may need to recalibrate some of its own trade policies. This includes addressing long-standing contentious trade policies such as supply management in dairy and poultry, while still defending key domestic industries where national interests warrant protection.

Canada has already shown flexibility by abolishing its digital services tax and lifting several counter-tariffs on U.S. goods. Moving forward, it will be important for the federal government to adopt policies that recognize the United States as Canada’s dominant trading and economic partner. This could mean stricter enforcement of rules of origin, tighter controls on steel and aluminum content and labour value thresholds or revisiting global de minimis rules for e-commerce.

At the same time, Canada can advance its own economic interests by reindustrializing in sectors that are important to U.S. supply chains. Many Canadian industries are raw material suppliers to the U.S.; with this in mind, moving up the value chain towards more intermediate or finished goods — particularly in agricultural products, critical minerals, forestry products and consumer products — could enhance our economic potential.

Despite the current U.S. administration’s protectionist stance, maintaining a strong and complementary trade relationship with Canada ultimately supports North American industrial and strategic goals, which is why an updated USMCA agreement is likely.

Diversifying Beyond the U.S. sphere of influence

While maintaining a strong partnership with the United States remains essential, Canada must also expand its global trade relationships and strengthen its domestic economy. Progress is already being made: in early November, the federal government announced new trade, economic, and defense partnerships with several Indo-Pacific nations, including South Korea, Chile, and Thailand.

Domestically, the introduction of Bill C-5, the One Canadian Economy Act, aims to accelerate infrastructure development and eliminate interprovincial trade barriers — steps that could enhance internal market efficiency and competitiveness. Meanwhile, the growing “Buy Canada” movement has helped offset some tariff-related challenges and provided new momentum for Canadian products in 2025.

It is important for Canada to reduce its reliance on U.S. trade over the long term, but we would like to reiterate that the USMCA remains crucial to Canada’s economic prospects. We are therefore closely watching developments In Washington and Ottawa as they can have far-reaching consequences for Canadian trade, the labour market and the overall growth outlook as we head into 2026.

Download PDF

Related Topics and Links of Interest:

©2025 Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd. Do not sell or modify this document without the prior written consent of Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd. This commentary represents the views of Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd. as at the date indicated. This document is not intended, and should not be relied upon, to provide legal, financial, accounting, tax, investment or other advice.

Certain portions of this report may contain forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements include statements that are predictive in nature, that depend upon or refer to future events or conditions, or that include words such as “expects”, “anticipates”, “intends”, “plans”, “believes”, “estimates” and other similar forward-looking expressions. In addition, any statement that may be made concerning future performance, strategies or prospects, and possible future action, is also forward-looking statement. Forward-looking statements are based on current expectations and forecasts about future events and are inherently subject to, among other things, risks, uncertainties and assumptions which could cause actual events, results, performance or prospects to be incorrect or to differ materially from those expressed in, or implied by, these forward-looking statements.

These risks, uncertainties and assumptions include, but are not limited to, general economic, political and market factors, domestic and international, interest and foreign exchange rates, equity and capital markets, business competition, technological change, changes in government regulations, unexpected judicial or regulatory proceedings, and catastrophic events. This list of important factors is not exhaustive. Please consider these and other factors carefully before making any investment decisions and avoid placing undue reliance on forward-looking statements Beutel Goodman has no specific intention of updating any forward-looking statements whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise.