Summary

In this piece, the Beutel Goodman Fixed Income team shares its perspective on the Fed’s most valuable asset, how it was built over time, and what it could mean for policy, the yield curve and the institution going forward.

By Beutel Goodman Fixed Income Team

Over the last four decades, the Federal Reserve (the Fed) has built something more durable than any single model, forecast or policy framework; they have built credibility. As the central bank of the United States, credibility is their most valuable asset, shaped over decades and tested through multiple crises, including the post-pandemic inflation scare. It is now once again back in the spotlight.

That credibility is not simply a ‘nice to have.’ It makes monetary policy work. When the Fed is trusted, its words do some of the work that its tools cannot. When it is doubted, every lever gets heavier, rate moves must be larger, balance sheet policy becomes more destabilizing, and market volatility becomes its own form of monetary policy tightening.

By statute, the Fed is directed to promote maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates. That third goal is often forgotten, treated as a footnote at best, but it is a useful bridge to the bond market. Moderate long-term rates are the byproduct of credibility, especially inflation credibility; investors will only accept lower long-term yields when they trust that purchasing power will be protected over time.

Independence Is the Foundation of Credibility

Credibility is not self-generated. The Fed’s credibility rests on independence: the ability to pursue its mandate without being pulled toward the short-term incentives of electoral cycles. Put simply, elected officials almost always prefer lower interest rates because they can boost growth and loosen financial conditions within a political term, especially heading into an election.

Independence gives central banks room to make tougher decisions that may be unpopular in the moment but are necessary to protect longer-run outcomes, particularly price stability. This is not just theory, and is not unique to the United States, it is a pattern observed across central banks globally. Decades of empirical work find that stronger central bank independence is associated with lower inflation and less inflation volatility. In many emerging markets, it is also associated with lower sovereign borrowing costs (Alesina and Summers, Cukierman et al., Klomp and de Haan, World Bank 2025).

The Federal Reserve, created in 1913, was designed to balance public accountability with insulation from day-to-day political pressure. The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) combines the Board of Governors with the presidents of the 12 regional Federal Reserve Banks, a structure meant to diffuse power and limit political influence. In its early decades, credibility was also anchored externally through the classical gold standard, when the dollar was defined as a fixed amount of gold.

Congress repeatedly reshaped the Fed in response to events, with the Great Depression driving reforms that strengthened the Board and clarified governance. In 1933, the U.S. abandoned the domestic gold standard as the deflationary panic made the gold constraint untenable. However, an official international dollar-to-gold link later persisted under the Bretton Woods system, but it was limited to foreign governments and foreign central banks. That distinction mattered as it created room for the U.S. to devalue the dollar against gold and pursue reflation. This eased financial conditions and supported credit creation, which helped lift the economy out of the worst of the Great Depression.

Governance evolved with these regime changes. The Banking Act of 1935 centralized power in the Board of Governors, strengthening decision-making and insulating policy from the executive while reducing the regional banks’ influence. Independence was reinforced in 1951 with the Treasury–Fed Accord, which separated debt management from monetary policy. This was widely treated as a foundational moment for the contemporary Fed, because the temptation to keep financing conditions artificially easy when public borrowing needs are large never disappears. The central bank’s restraint is easier to maintain when institutional boundaries are clear.

From Volcker to Powell: Chair Eras, Credibility and the Expanding Toolkit

In more modern times, the Fed’s credibility story is easiest to see through successive Chairs. The end of the Bretton Woods system in 1971, severed the final link between the dollar and gold, which meant that the burden of anchoring expectations shifted more decisively to the institutional credibility and independence of the Fed itself.

Inflation pressures had already been building since the mid 1960s, but the years after Bretton Woods collapsed, marked the most acute phase of The Great Inflation. That period was fueled by repeated energy price shocks, rising fiscal imbalances tied to major spending programs, a widening deficit associated with the Vietnam War, and persistent demand pressures. In combination, these forces produced the era’s signature mix of high inflation and weak growth, the infamous stagflation problem.

Arthur Burns, Fed Chair for most of the 1970s’ inflation run-up, is often associated with a credibility failure. As the Nixon administration tried to manage inflation with wage and price controls, the Fed under Burns maintained an accommodative stance, and inflation remained persistently high. Over Burns’s tenure, CPI inflation spiked sharply, reaching 11.1% in 1974, and stayed elevated into the late 1970s. Investors demanded more compensation for inflation risk, and nominal long-term yields rose.

It was not until Paul Volcker stepped in as Fed Chair that credibility began to rebuild. In October 1979, the Fed tightened aggressively to rein in inflation, with the federal funds rate nearing 20%. Inflation subsequently fell sharply from its early 1980 peak of 14.6% and by 1983 was running near 3% in CPI terms. The cost was severe; the U.S. experienced back-to-back recessions. This downturn was the signal markets needed. The Fed was willing to tolerate near-term economic pain to re-anchor expectations and rebuild central bank credibility.

The Alan Greenspan era, spanning the mid-1980s through 2007, is often described as the Great Moderation, a long stretch of lower inflation, less volatility and longer expansions. This period compounded trust: the institution’s reaction function felt more predictable. The long end of the curve remained relatively well anchored because the inflation regime appeared stable, before the period ultimately ended with the financial crisis.

The 2008-09 crisis response under Ben Bernanke permanently broadened the Fed’s toolkit. With policy rates at the zero lower bound, forward guidance became an explicit lever and balance sheet policy, or quantitative easing (QE), became mainstream as the Fed bought longer-term securities to push down yields and support the recovery.

Janet Yellen’s tenure and the first half of Jerome Powell’s reinforced continuity and gradualism, with a steady emphasis on maximum employment, helping preserve credibility. That steadiness set the stage for the pandemic response, when the Fed moved with speed and scale, using both rate cuts and the balance sheet purchases to stabilize markets and support the economy. After the pandemic, the task flipped. As inflation surged, with CPI up 9.1% year over year in June 2022, the Fed shifted to restoring price stability, raising rates by 525 basis points and beginning balance sheet run-off in June 2022.

Across these eras, the Fed’s tools expanded. But the constant was that markets rewarded credible, independent decisions. This can be seen through the U.S. Treasury yield curve which is the clearest real-time scorecard of the institution’s credibility.

The Yield Curve: The Bond Market’s Instrument Panel

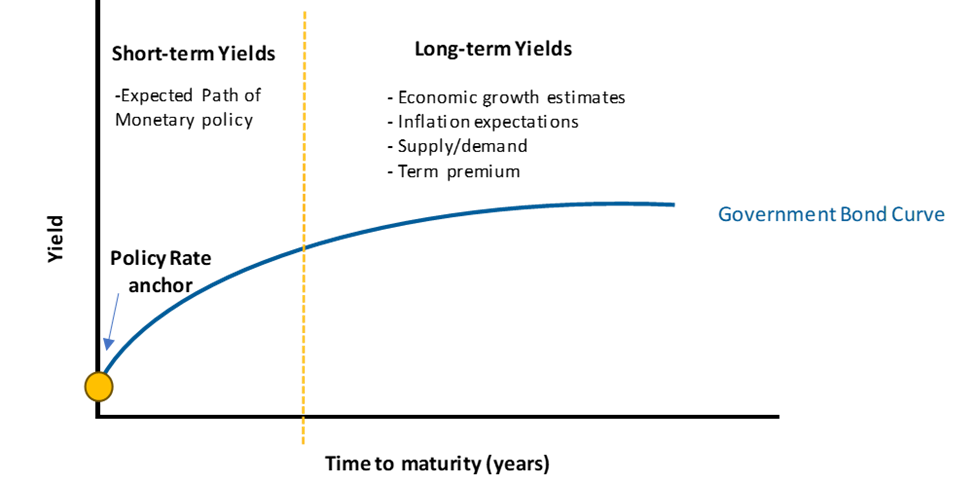

Yield curve data helps investors read the market’s real-time judgment on three things: (1) the current stance of policy, (2) expectations for the path of policy, and (3) the credibility of the inflation anchor. These forces show up in different parts of the yield curve.

- Very front end: anchored by the policy rate

- Short to mid term (1-5 years): market’s estimate of the Fed’s near-term path, and assessment of restrictiveness of policy is now

- Long term (10-30 years): market’s confidence in long-run growth, inflation, and the risk premium investors demand to hold duration (term premium + inflation risk premium)

- Curve shape: interaction of the short-to-long parts of the curve, a signal about whether policy is tight enough to balance growth and inflation

Exhibit 1. The Bond Market’s Instrument Panel. The following chart shows a stylized representation of a normal (upward sloping) yield curve. The front end is anchored at the policy rate. Short-term yields reflect the expected path of monetary policy and long-term yields reflect economic growth estimates, inflation expectations, supply/demand dynamics and the term premium.

Source: Beutel Goodman

This link between monetary policy and the yield curve is why credibility has such direct market consequences. When credibility is questioned, long rates can rise even as the Fed is cutting while investors demand a higher risk premium. That dynamic showed up in the mid-1970s under Arthur Burns. The effective federal funds rate fell materially through 1974 and 1975. Yet longer-term Treasury yields remained elevated, and the curve steepened as investors priced higher inflation risk and weakening confidence in the inflation anchor.

By contrast, when credibility is high, long-term rates can remain relatively moderate even when the Fed is tightening aggressively. During the post-pandemic hiking cycle, the curve inverted: the front end repriced sharply with policy expectations while longer-term yields moved less than the front end. This is consistent with a market that believed inflation would be contained over time and that the long run regime remained stable.

In this sense, the inversion was not a recession signal; instead, it was a credibility signal. While many were quick to criticize the Fed’s imperfect inflation response, it was the Fed’s credibility that anchored longer-term yields. This limited how restrictive financial conditions became, which allowed the economy to avoid a recession in 2023.

What’s Next for Fed Cred with Warsh at the Head?

Central bank credibility is always important, but the relevance of the independence debate has intensified recently. On January 30, 2026, the White House announced President Trump’s nomination of Kevin Warsh as the next Fed Chair. The nomination lands at a moment when the Fed is already under unusually bright political and legal scrutiny, including administrative pressure over the path of rates, DOJ subpoenas tied to the Fed’s Washington renovation project, and the ongoing Lisa Cook case at the Supreme Court.

The U.S. Administration’s nomination of Warsh is important because he is arguably the most traditional short-listed candidate from the market’s perspective. He served as a Fed governor from 2006 to 2011 and has generally been viewed as an inflation hawk, a posture that tends to reassure bond investors. At the same time, he has been a prominent critic of post-crisis monetary policy.

A central plank of Warsh’s narrative is that the economy may be entering a higher productivity regime, increasingly shaped by AI. He has long advocated shrinking the Fed’s balance sheet to reduce monetary dominance, arguing that heavy reliance on QE invites political and fiscal pressure. In his view, a smaller balance sheet restores a tighter, more rules-based approach focused on price stability.

However, a faster balance sheet run-off would, by definition, tighten financial conditions; therefore, cutting rates could be used to offset some of that tightening at the front end. His working premise is that a smaller Fed footprint and a productivity-driven AI disinflation tailwind could keep longer-term yields contained, even as policy eases. This would also lower the debt burden on the U.S. and thus exert further downward pressure on the term premium.

The risk is that multiple things need to go right. At a minimum, rates would need to fall without reigniting inflation, AI would need to deliver sustained productivity gains rather than a one-time boost to margins, and Warsh would need to build consensus within the FOMC while staying insulated from day-to-day political influence, a prerequisite for independence and credibility.

Warren Buffett once said, “It takes 20 years to build a reputation and five minutes to ruin it.” If credibility slips, the yield curve will show it first, via higher-term premia, higher inflation risk premia, and higher long end volatility. The feedback loop is painful. Higher long rates tighten financial conditions for everyone, raising government borrowing costs, lifting mortgage rates, widening credit spreads and increasing the discount rate applied across risk assets.

Credibility is the benefit of the doubt premium. Central banks will always be imperfect forecasters, and the goal is not perfection; the goal is maintaining control of expectations. When credibility is intact, policymakers can miss a data point or misread the timing of a turning point without sacrificing the long-run confidence that keeps inflation expectations well anchored and supports stable financial markets. That premium was rebuilt after The Great Inflation, proven under Volcker, and reinforced by subsequent Chairs who expanded tools that only work when the markets believe. In 2026, we expect that credibility to hold. The yield curve will be the first place to look for confirmation.

Download PDF

Related Topics and Links of Interest:

©2026 Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd. Do not sell or modify this document without the prior written consent of Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd. This commentary represents the views of Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd. as at the date indicated. This document is not intended, and should not be relied upon, to provide legal, financial, accounting, tax, investment or other advice.

Certain portions of this report may contain forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements include statements that are predictive in nature, that depend upon or refer to future events or conditions, or that include words such as “expects”, “anticipates”, “intends”, “plans”, “believes”, “estimates” and other similar forward-looking expressions. In addition, any statement that may be made concerning future performance, strategies or prospects, and possible future action, is also forward-looking statement. Forward-looking statements are based on current expectations and forecasts about future events and are inherently subject to, among other things, risks, uncertainties and assumptions which could cause actual events, results, performance or prospects to be incorrect or to differ materially from those expressed in, or implied by, these forward-looking statements.

These risks, uncertainties and assumptions include, but are not limited to, general economic, political and market factors, domestic and international, interest and foreign exchange rates, equity and capital markets, business competition, technological change, changes in government regulations, unexpected judicial or regulatory proceedings, and catastrophic events. This list of important factors is not exhaustive. Please consider these and other factors carefully before making any investment decisions and avoid placing undue reliance on forward-looking statements Beutel Goodman has no specific intention of updating any forward-looking statements whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise.