Summary

The relationship between Canada and the U.S. is often mutually beneficial, particularly when it comes to the health of their respective economies. In this piece, the Beutel Goodman Fixed Income team looks at how the economic performance of the two countries has recently diverged and what this could mean for bond investors.

By Beutel Goodman Fixed Income Team (as at June 6, 2024)

In the best of times, in the worst of times, in ages of wisdom, in ages of foolishness, Canada and the United States have forged deep historical, cultural and economic ties.

Sharing the world’s longest land border, the two countries have a strong trade relationship, and according to the Federal Government of Canada, approximately C$3.6 billion worth of goods and services crossed the Canadian/U.S. border daily in 2023. Despite the differences in size, the two economies and their respective financial markets have historically been linked, and both have a generally stable exchange rate, as well as highly correlated equity and bond markets.

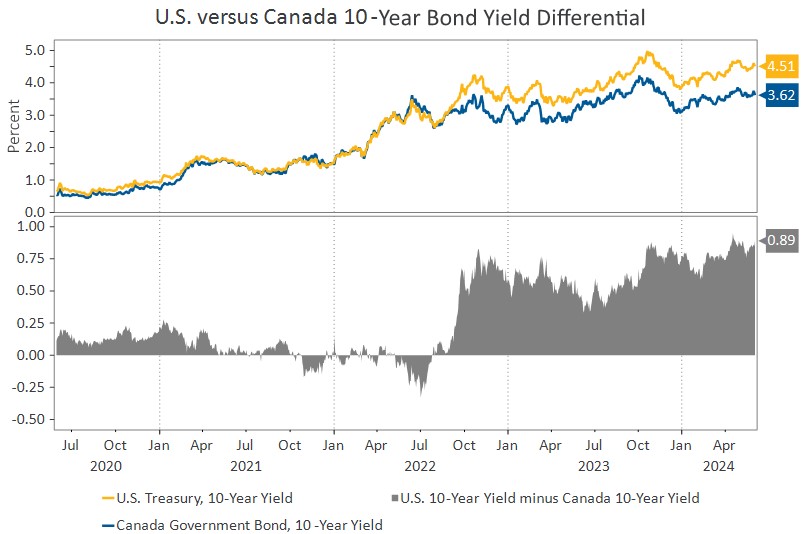

Recent periods have challenged this typically stable financial relationship, with the U.S. minus Canada 10-year government bond yield differential reaching historically wide levels. This commentary explores the current U.S.-Canada economic relationship and what it may mean for bond markets.

Post-Pandemic Convergence

In the post-pandemic era, the economic trajectory of the U.S. and Canada was initially largely in lockstep. At the beginning of the crisis, as economic uncertainty prevailed, both Canada and the U.S. were quick to provide fiscal and monetary stimulus for their faltering economies to both businesses and consumers.

Supply/demand imbalances then rose sharply as pandemic stimulus buoyed demand, while supply chain challenges and lockdowns meant that the supply side of the economy ground to a halt. This resulted in an increase in overall price levels, led by goods inflation, and then gradually, as the economy reopened, translated into elevated and sticky services inflation.

Responding to the heightened inflation, the U.S. Federal Reserve (the “Fed”) and the Bank of Canada (the “BoC”) were largely on the same page in terms of tightening monetary policy. Both central banks undertook quantitative tightening and aggressively and rapidly hiked interest rates — the Fed hiked rates to 5.25–5.50% and the BoC hiked to 5%.

A Fork in the Road

As the central banks embarked on their hiking cycles in mid-2022 and into 2023, the financial markets of the U.S. and Canada slowly began to diverge. This divergence accelerated in the second half of 2023 as additional rounds of fiscal stimulus in the U.S. drove economic resilience, particularly through fiscal programs such as the CHIPS and Science Act, as well as the Inflation Reduction Act, which were both signed in 2022. In contrast, Canadian growth, without major fiscal stimulus, began to fade.

The difference between 10-year Government of Canada bond yields and U.S. Treasuries reached 95 bps in April 2024 (the widest spread since 1982) and remains at 89 bps, as at May 31, 2024.

Exhibit 1: U.S. versus Canada Bond Spreads. This chart shows the U.S. Treasury 10-Year yield and the Canada Government Bond 10-Year yield from May 2020 to May 2024. During mid-2022, the difference in the 10-year yield of the two countries began to diverge and was at 89 bps, as at May 31, 2024.

Source: Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd., Macrobond Financial AB, U.S. Department of Treasury, as at May 31, 2024.

Another difference in bond market pricing between Canada and the U.S. can be found in corporate credit spreads. Though the index compositions vary somewhat, the difference between the Option Adjusted Spread (OAS) of the Bloomberg Canada Aggregate Baa Total Return Index and the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Baa Total Return Index is also at historically wide levels. In the U.S., spreads of the Bloomberg index are approaching the low levels last seen in 2021 and prior to the Global Financial Crisis, whereas spreads in Canada are still about 17 bps away from their tightest levels.

Economies Diverge

The differences in bond market valuations largely reflect the positive economic growth outlook, hotter inflation and stronger labour market backdrop for the U.S.

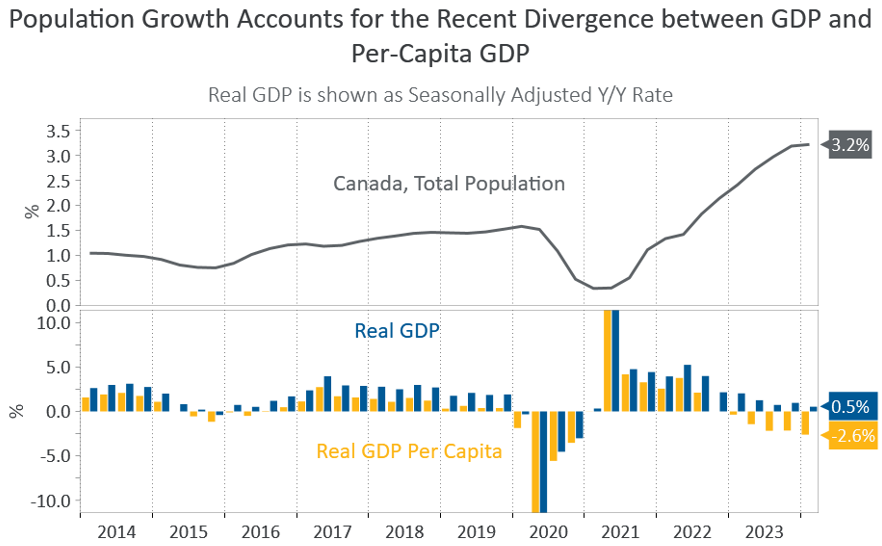

In fact, as we approach the mid point of 2024, Canada would have already experienced a technical recession (two successive quarters of economic decline) were it not for elevated immigration levels inflating its GDP (see Exhibit 2). In contrast, the U.S. has experienced robust year-over-year growth of 2.9% for Q1/2024, which, when divided by the total population, translates to per-capita growth of 2.4%.

Forward growth expectations also highlight this economic divergence, with Bloomberg News’ May Economic Forecast showing that the U.S. is expected to expand 1.4% faster than Canada in 2024.

Exhibit 2: Population Growth in Canada and GDP per Capita. The top pane in the chart below shows the year-over-year population growth for Canada for the last 10 years, with the population growth rate increasing sharply in the last two years. The bottom pane shows the year-over-year growth rate of seasonally adjusted Canadian Real GDP and Real GDP per capita for the last 10 years. During the past five quarters, Real GDP per capita has been negative on a year-over-year basis.

Sources: Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd, Statistics Canada, Macrobond, as at May 31, 2024.

Recently, the inflation backdrop has painted a slightly different picture in Canada compared to the U.S. In Canada, inflation has been tracking downwards for some time, with the Consumer Price Index (CPI) year-over-year reading for April 2024 at 2.7%, comfortably within the central bank’s 1–3% target range.

In the U.S., things are a little more complicated, as CPI tracked upwards in Q1/2024, sparking fears of reflation. In April 2024, year-over-year CPI sat at 3.4%, with core inflation in that same range. Canada is therefore within reach of the BoC’s 2% inflation target, whereas the U.S. is further off.

Another key indicator of economic activity is the labour market. The U.S. job market is in a much stronger position than Canada, benefitting from more positive consumer sentiment. The U.S. unemployment rate stood at 3.9% in April and has remained between 3.7% and 3.9% since August 2023. Unemployment claims have also been well contained and job growth has been fairly robust.

Canada’s unemployment rate has been trending higher since 2022, from a low of 4.9% in July 2022 to the latest reading of 6.1% for April 2024. However, it is important to note that this 1.2% increase in unemployment has not been on the back of job losses; rather, population growth has increased the size of the labour market (the denominator in the equation). This increase in the labour market has not been fully absorbed into jobs, raising the unemployment rate.

We estimate that in order to maintain the current unemployment rate, the Canadian labour market needs to add 50,000 jobs per month. Employment growth in the last 24 months has been well below the break-even rate, setting a high bar for employment growth in the coming months, making it likely that the unemployment rate may increase further.

The economic implications of an increasing unemployment rate due to labour market growth are less direct than outright job losses. However, it is likely that in time, this dynamic could put downward pressure on wages and could eventually lead to job cuts as companies rotate jobs to new entrants into the labour force who potentially command lower pay. The unemployment rate going up because of labour force growth would therefore likely have a more gradual effect on layoffs and discharges than if the unemployment rate went up for purely economic reasons.

In addition, there is the negative emotional impact of a higher unemployment rate. Companies may be sensitive to an increasing unemployment rate and may pre-emptively cut back on growth and hiring plans, which can then create a feedback loop of lower consumer spending leading to lower demand and a further weakening of the labour market.

Presently, it appears that financial markets are reacting to the economic reality that a recession is more likely in Canada than the U.S., where there is a greater chance of a soft landing. This is putting greater downward pressure on Canadian bond yields and upward pressure on Canadian credit spreads relative to the U.S. However, forecasting the extent of this divergence is difficult given the unique circumstances of the post-pandemic period.

Never Underestimate the Power of the Consumer

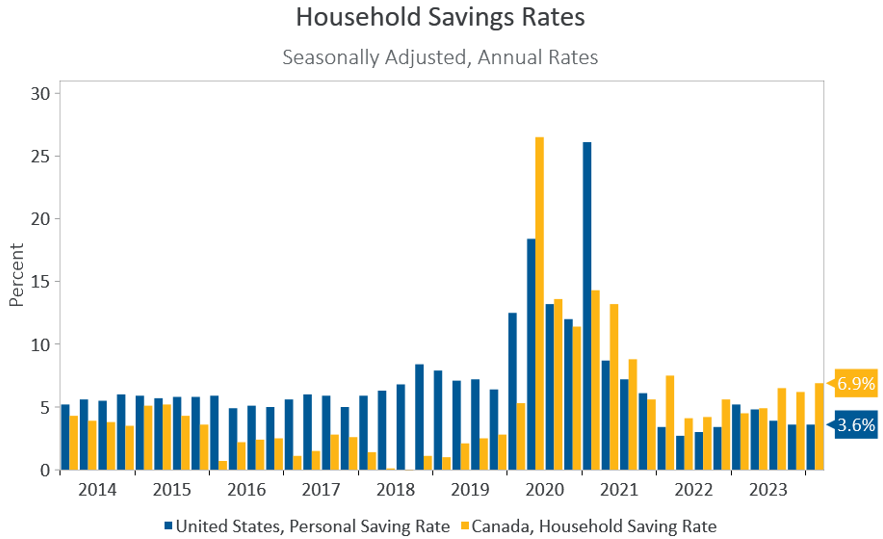

Are the differences between the Canadian and U.S. economies a symptom of Canada’s interest rate sensitivity or is Canada acting as a leading indicator for where the U.S. is headed? A key difference between the Canadian and U.S. economies currently is the strength and power of the U.S. consumer. Personal consumption expenditures in the U.S. account for nearly 70% of GDP. Consumers, boosted by low household debt levels, stimulus cheques and increasing wages, have driven much of the economic resilience in the U.S. since 2022.

The Canadian consumer, in contrast, tends to be much more conservative and has been less of a tailwind to economic growth. A comparison of saving rates is displayed in Exhibit 3 and shows that in the last year, the savings rate in the U.S. is low compared to historical periods and compared to Canada. Canadian consumers have also increased their savings rate.

Exhibit 3: Savings rates in the U.S. and Canada. This chart shows the household savings rates of the U.S. and Canada. The U.S. savings rate is currently lower than in Canada.

Sources: Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd., U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), Statistics Canada, as at May 31, 2024.

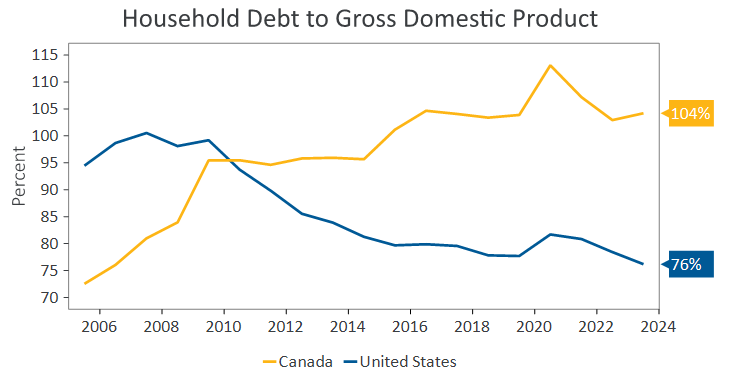

Exhibit 4 shows that household debt levels in the U.S. are at 76% of GDP after a period of significant deleveraging following the Global Financial Crisis. The Canadian consumer, by comparison, has a household debt to GDP of 104%. This is important because leverage pulls forward spending potential into the present, and therefore high leverage rates can impair the future spending potential of an economy.

Exhibit 4: Household Debt to GDP. This chart shows U.S. and Canadian household debt to GDP from 2005 to 2024. U.S. debt to GDP steadily declined after the Global Financial Crisis, whereas Canadian debt to GDP has increased.

Sources: Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd., International Monetary Fund, as at May 31, 2024.

The Mortgage Effect

Higher rates of leverage among Canadian consumers means they must spend more on debt servicing costs. At current higher levels of interest rates, these debt service payments divert money from the goods and services side of the economy. This is especially true with respect to the Canadian housing market, where debt levels are higher and the pass-through of higher interest rates to the consumer is faster than in the U.S.

The Canadian housing market is dominated by variable-rate mortgages and 5-year fixed rate mortgages that often have stiff prepayment penalties. Canadian homeowners are exposed relatively quickly to the pass-through of market interest rates, since their debt service cost changes each time their mortgage resets. The reset is immediate in the case of variable rate mortgage holders and is every five years in the case of 5-year fixed rate mortgage holders. Since mortgage rates have increased materially in Canada since 2022, this new higher rate means that homeowners have less disposable income to spend on other goods and services.

In the U.S., mortgages are skewed to 30-year fixed-rate mortgages with no prepayment penalties. This allows U.S. mortgage holders the option to lower their mortgage rate if rates dip below their current contracted rate or keep their existing contracted rate for a 30-year period. This makes U.S. homeowners much less sensitive to higher interest rates, so the impact of higher mortgage rates in lowering household discretionary spending activity is less pronounced.

In Canada, higher rates have already impacted variable-rate mortgage holders, from either higher monthly payments for those with adjustable payment variable rate mortgages, or in the form of lengthened amortization periods for those that have fixed payment variable rate mortgages. For holders of fixed-rate mortgages, however, the pain is yet to come; as of Q1/2024, 62% of outstanding mortgages were originated or renewed at lower rates pre-2022 and have still yet to be reset at higher rates. For mortgages up for renewal in 2025 and 2026, monthly mortgage payments are expected to increase by about 18–20%, drawing money away from other parts of the economy.

It is not all doom and gloom though, as there is also housing market appreciation in Canada. In addition, Canadian banks are well capitalized and do not expect to face significant drawdowns if the housing market does correct.

Stability in the Canadian housing market and economy at large is closely related to what happens in the labour market and whether the unemployment rate remains contained. The same can be said for the U.S., where the consumer is driving much of the growth in GDP. The continued health of the economy is closely tied to the stability of the job market in maintaining income levels and consumer demand.

Central Banks at a Crossroads

A key part of bond investing is estimating where the economy and interest rates may be years down the line. This means analyzing all the available data to identify trends as they are developing. For central banks, it is about weighing the costs and benefits of their policy actions – as Fed Chair Jerome Powell said during his March 20, 2024 press conference, “If we ease too much or too soon, we could see inflation come back, and if we ease too late, we could do unnecessary harm to employment and people’s working lives.”

The conditions (and data) in Canada led the BoC to reduce its key rate by 25 bps at its June meeting. South of the border, as long as unemployment remains low, the Fed can be patient and maintain rates at current levels while inflation remains a concern. Minutes from the Federal Open Market Committee gathering in early May this year stated that “it would take longer than previously anticipated for them [Fed officials] to gain greater confidence that inflation was moving sustainably toward 2%.” Fed officials have increasingly discussed the prospect of “higher for longer” interest rates in recent weeks.

This begs the question of whether eventual rate cuts will provide the necessary stimulus to buoy the economy and secure the coveted soft-landing.

Securities markets have already priced in rate cuts beginning in 2024, with the market expecting the BoC to cut to 3.25% in Canada and the Fed to cut to about 4% in the U.S. Given that the yield curve has already incorporated the expected path of easing, in a cutting cycle, long-term yields may not fall as much as expected.

In fact, because Canada has priced in a terminal rate 75 bps below the U.S. and the divergence between long-term yields of the two countries is so wide, it may be difficult for Canadian yields to rally materially, unless the U.S. yield curve follows suit.

This further implies that in Canada, mortgage rates may not fall in concert with policy rate easing. Therefore, a policy rate decrease may not provide the expected relief to an already indebted Canadian consumer.

In the U.S., even with rate cuts, consumers may begin to feel the pinch in the next 12 months as pandemic stimulus runs out. This will leave the consumer with two options: pull back spending or take on debt to finance consumption. Both would likely result in a slow down, the first through a decrease in aggregate demand and the second through a substitution effect of interest payments for consumption.

We are already seeing rising debt service costs in the U.S. leading to increasing consumer loan delinquencies. If these trends continue and U.S. consumer strength begins to wane, we may eventually see an increase in the savings rate, which would further impair spending.

As it stands, we believe that the full extent of the interest rate hikes in 2022–2023 has yet to be felt, and a recession in Canada might still occur later in 2024. In Canada, the performance of financial markets will take its cue from the U.S., as will the depth of any economic drawdown.

Continued resilience in the U.S. economy should benefit Canada and limit the extent of a downturn. The old adage, “When America sneezes, the rest of the world catches a cold”, is as true today as it ever was and no more so than in Canada. Should the U.S. avoid catching a cold altogether, this should ultimately benefit Canada.

Download PDF

Related Topics and Links of Interest:

©2024 Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd. Do not sell or modify this document without the prior written consent of Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd. This commentary represents the views of Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd. as at the date indicated.

This document is not intended, and should not be relied upon, to provide legal, financial, accounting, tax, investment or other advice.

Certain portions of this report may contain forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements include statements that are predictive in nature, that depend upon or refer to future events or conditions, or that include words such as “expects”, “anticipates”, “intends”, “plans”, “believes”, “estimates” and other similar forward-looking expressions. In addition, any statement that may be made concerning future performance, strategies or prospects, and possible future action, is also forward-looking statement. Forward-looking statements are based on current expectations and forecasts about future events and are inherently subject to, among other things, risks, uncertainties and assumptions which could cause actual events, results, performance or prospects to be incorrect or to differ materially from those expressed in, or implied by, these forward-looking statements.

These risks, uncertainties and assumptions include, but are not limited to, general economic, political and market factors, domestic and international, interest and foreign exchange rates, equity and capital markets, business competition, technological change, changes in government regulations, unexpected judicial or regulatory proceedings, and catastrophic events. This list of important factors is not exhaustive. Please consider these and other factors carefully before making any investment decisions and avoid placing undue reliance on forward-looking statements Beutel Goodman has no specific intention of updating any forward-looking statements whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise.