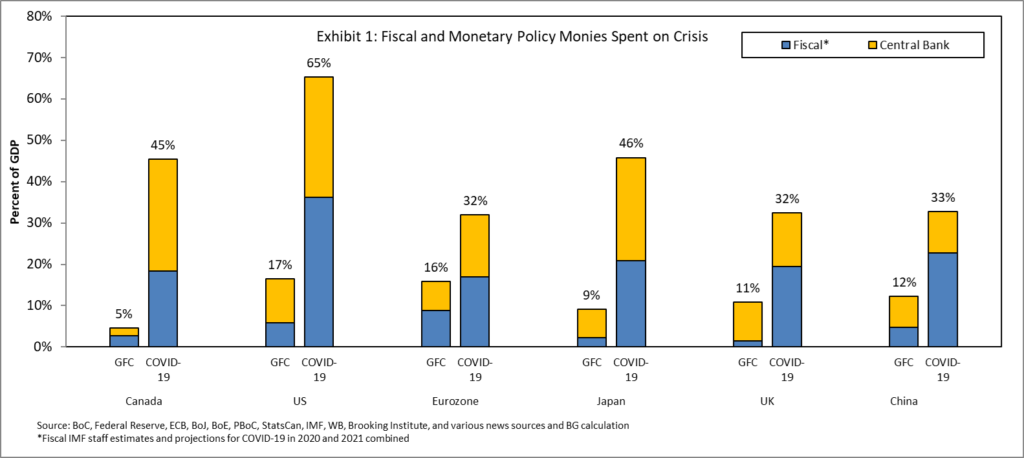

Global central banks and sovereign governments have spent record amounts of stimulus — in fact, it dwarfs what was spent during the entire GFC and is approaching WWII levels — to help the economy ride out the disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic (see Exhibit 1). The U.S. Congress is currently debating an additional stimulus package of US$1 trillion to US$3 trillion. Governments and central banks have seemingly embraced Mosler’s[1] Law, which states that no financial crisis is so deep that a sufficiently large fiscal adjustment cannot deal with it.

To begin with, we should clarify that we believe this stimulus was necessary and we are not arguing against it. Economies had been stopped in their tracks by shelter-in-place restrictions, and millions of unemployed and/or furloughed workers, as well as businesses that were shuttered, needed immediate support. In addition, the bond market was not functioning properly, which impeded funding flows.

We were well prepared as to how to position the fixed income portfolio, having learnt from previous crises. Adhering to the old adage of “don’t fight the Fed”, as soon as central banks started to announce their quantitative easing programs we increased our credit exposure and lengthened the duration of our credit, where possible. Central bank backstopping of the markets is a risk-on event.

However, we also believe it’s critical to understand the long-term effects from the significant amount of money that has been spent. Governments’ deficits are climbing and debt/GDP ratios are rising well above the 90% level. The International Monetary Fund predicts that public debt for advanced economies will exceed 130% of GDP in 2020-21 and the average overall fiscal deficit is expected to soar to 16.5% of GDP in 2020, 13 percentage points higher than the previous year[2].

As the economics adage taught us, there is no such thing as a free lunch. Economic professors Kenneth Rogoff and Carmen Reinhart wrote a research paper in 2010 titled “Growth in a Time of Debt”[3]. In the report, the authors argue that using data across all advanced countries, when debt/GDP is greater than 90%, growth is typically lower than countries with lower debt/GDP ratios. One caveat is that not all advanced countries are the same; for example the U.S., with its reserve currency, is very different than Greece or Italy.

Credit-rating downgrades are one consequence of running higher deficits and debt burdens. Canada lost one of its prized AAA credit ratings when Fitch Ratings downgraded its sovereign rating by one notch to AA+ from AAA. The other three major credit-rating agencies have reaffirmed Canada’s AAA rating, but the federal government will likely need to show a path to how it will reduce its debt/GDP ratio over time to safeguard Canada’s ratings.

With elevated debt levels and deficits, there is also concern that governments do not have enough capacity to spend during the next recession and that inflation may rise from the enormous extent of governments spending. Nevertheless, interest rates are likely to stay lower for longer as governments need to finance their budget deficits and monetary policy needs to remain stimulative.

All this stimulus raises the question of whether inflation will return. An increase in pent-up demand could very well lead to positive inflationary pressures down the road. “Good inflation”, which is defined as demand-driven inflation, drives up prices from increased demand for goods. “Bad inflation”, on the other hand, is defined by an increase in the cost of production. This is also a risk because although it would help by lowering real debt, it would be offset by the decrease in growth from reduced supply. “Bad inflation” may be possible as supply constraints and the reversal of globalization drive up prices.

However, we believe that the risk of higher inflation remains low in the near term. The output gap (the difference between potential GDP output and actual output) is currently wide and will likely remain so as it will take some time for employment to return to pre-pandemic levels. Furthermore, secular pressure from an ageing population and the push towards automation will likely continue to place downward pressure on inflation.

Despite stimulus, monetary policy cannot fix corporate solvency problems and there is some concern that the central bank backstop of the corporate bond market, and its venturing even into the high yield market, is creating moral hazard. There is legitimate concern of a new preponderance of zombie companies, which likely would have died a natural death during this crisis as they were over-levered or their business model/strategy did not work and are being kept alive by stimulus programs.

In addition, fiscal programs in the U.S. are expiring and we have yet to see the second wave that could put fiscal policy back into action to alleviate an already weakened economy. Eventually the global economy will recover, interest rates will rise and governments will face increasing and possibly punitive debt-servicing costs that could crowd out other spending requirements. This would unfold at a time when health care costs are expected to rise with an ageing population.

We are in unprecedented times. Although the amount of stimulus was warranted, like a sick patient in need of medication, the question one must ask now is, once the patient recovers, will they remain dependent on the cure? Only time will tell.

Notes

[1]Note: Warren Mosler is a U.S. economist and one of the leading proponents of Modern Monetary Theory

[2]World Economic Outlook Update, International Monetary Fund, June 2020.

[1]Rogoff, Kenneth and Reinhart, Carmen, “Growth in a Time of Debt”, Working Paper 15639, National Bureau of Economic Research, January 2010.

Related Topics and Links of Interest:

- Modern Monetary Theory: Voodoo Economics?

- The New Abnormal: Where is the L U V ?

- Wealth Inequality: The Gilded Age 2.0

- Beutel Goodman mutual fund profiles

©2020 Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd. Do not copy, distribute, sell or modify this document without the prior written consent of Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd. All opinions and estimates expressed in this document are as at June 4, 2020 and are subject to change without notice.

This document is not intended, and should not be relied upon, to provide legal, financial, accounting, tax, investment or other advice. This is not an invitation to purchase or trade any securities. Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd. does not endorse or recommend any securities referenced in this document.

Certain portions of this commentary may contain forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements include statements that are predictive in nature, that depend upon or refer to future events or conditions, or that include words such as “expects”, “anticipates”, “intends”, “plans”, “believes”, “estimates” and other similar forward-looking expressions. In addition, any statement that may be made concerning future performance, strategies or prospects, and possible future portfolio action, is also forward-looking statement. Forward-looking statements are based on current expectations and forecasts about future events and are inherently subject to, among other things, risks, uncertainties and assumptions which could cause actual events, results, performance or prospects to be incorrect or to differ materially from those expressed in, or implied by, these forward-looking statements.

These risks, uncertainties and assumptions include, but are not limited to, general economic, political and market factors, domestic and international, interest and foreign exchange rates, equity and capital markets, business competition, technological change, changes in government regulations, unexpected judicial or regulatory proceedings, and catastrophic events. This list of important factors is not exhaustive. Please consider these and other factors carefully before making any investment decisions and avoid placing undue reliance on forward-looking statements. Beutel Goodman has no specific intention of updating any forward-looking statements whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise.