As we wind down 2021, markets are processing a number of challenges that seem likely to impact investment decisions in the coming year. We recently sat down with Steve Arpin, Managing Director, Canadian Equities, Rui Cardoso, Managing Director, U.S. and International Equities, and Derek Brown, Senior Vice President and Co-Head of Fixed Income, to address these important questions for 2022:

- How have inflation & supply-chain disruptions affected the asset classes and BG portfolios?

- How might central bank policy change the opportunities available in the market?

- How are valuations impacting the positioning of the portfolios?

The recording took place on November 29, 2021. The following transcript is edited for clarity.

Matt Padanyi: Hello, everybody. Thank you for logging on to our webinar today, “Three Key Questions for 2022 Answered”. The goal of our session today is to, of course, answer the questions that we’re hearing regularly from clients as we look forward to the new year.

My name is Matt Padanyi, I’m the Content and Communications Manager for Beutel Goodman, which means I basically have the pleasure of being the guy who gets to ask our experts the questions. Today I’m joined by Steve Arpin, Managing Director of Canadian Equities, Derek Brown, Senior VP and Co-Head of Fixed Income, and Rui Cardoso, Managing Director of U.S. And International Equities.

You all saw the questions on the invite, so I’ll just jump into it. But a quick housekeeping note to start. This is a webinar, so that means that all attendees are essentially in a listen-only mode. There is a Q&A function open. If you want to ask a question, you can type it in there. However, given the time constraints and the big topics that we’re dealing with, there’s a chance that it might not get answered. If that’s the case, I’ll have the questions and we will be sure to connect with you after the fact so that we can get you an answer. We won’t leave you hanging.

Note, this event represents the views of Beutel Goodman & Company as at November 29, 2021. It is not intended and should not be relied upon to provide legal, financial, accounting, tax, investment, or other advice. And this is not an invitation to purchase or trade any securities. Beutel Goodman & Company does not endorse or recommend any securities referenced within this presentation.

That’s all said and done. So, let’s get right to it. I’ll start with the first question and I’m going to go to Steve Arpin with this one.

Steve, how have inflation and supply chain disruptions affected the asset classes as well as the BG portfolios that you manage?

Steve Arpin: Thanks, Matt. And good afternoon, everybody. So, before I turn to answering the question of what we’re seeing in terms of inflation and supply chain disruptions currently, I just want to refresh everybody on the process that we use at Beutel Goodman and what we’ve been seeing over the last year and a half. Many of you will be familiar with the idea that we focus on buying businesses when they’re trading at significant discounts to our estimate of their intrinsic value. And we view intrinsic value of a business as the present value of future free cash flow. It really has to do with our confidence in that free cash flow stream, which brings in ideas like the quality of the business, the balance sheet, the sustainability of the business. When we have more competitive advantage and more certainty around that, then, in our view, as a business trades at a more and more significant discount to that intrinsic value, it provides an opportunity, and it provides a lower risk to you as an investor.

If we look back at what we’ve seen through the pandemic, in this downturn we had a very high level of trading activity in the Canadian Equity portfolio. And that really mirrors the experience that we had in 2008. Now we had businesses that traded at substantial discounts to what they were worth, but obviously for a whole different reason in this pandemic versus 2008.

So, one example of a security that we bought that will explain our process is CAE, which was not in the portfolio prior to that. CAE is a business that is very high quality, it’s dominant in aerospace training simulators and has been for years. And obviously with the onset of COVID, there was huge fear in the market about training requirements for pilots declining.

We were pretty confident that training requirements were going to continue and there wasn’t technological risk or disruption. But what we were also counting on is the airline business would need money because they were hemorrhaging cash. So, there was a need for further asset sales and further outsourcing, and that would benefit CAE. So, the company could grow secularly, even though there were challenges in the market. And we viewed CAE as an excellent free cash flow generator that was trading at a discount to our estimate of what it was worth at the time. Of course, the concerns were the collapse of travel [and] economic uncertainty. But, if the discount is large enough, you can arbitrage that time recovery. And obviously we do, as value investors, have a view about mean reversion and normalization.

So, the point that I’m making is that when we’re making investments, we are sector agnostic. We’re looking for sustainable free cash flow. We’re looking for certainty around that. And then when we get a discount to intrinsic value that’s sufficient, we’re going to take advantage of that. So, market disruptions or large discounts to estimates of business value will drive decisions in the portfolio.

Let’s turn to the question that Matt asked, which [are] the macro issues of today, inflation and supply chain disruptions. And these are really completely different from what we’ve been dealing with as we’ve made these changes, and I will say weren’t necessarily contemplated at the time because we were dealing much more with a situation where there was a lack of demand and concern around how certain could you be about business recovery?

If we look at these two specific questions, let’s look at supply chain first. There has been an impact in the market and the place that we’ve seen it most clearly has been in consumer discretionary, specifically automotive. Many of you will know that we own Magna, for example, which has been a secular grower in the automotive business. And we believe that if there is supply chain disruption or further supply chain disruption, it may provide us an opportunity to own more of that stock. Another thing that has been affected has been consumer durable. And this is related to the chip shortages we’ve seen coming from Asia.

So, on the supply chain, the best information is available in the automotive sector because it’s looked at so clearly all the time, globally. What we are seeing is that freight rates are declining, so that’s a positive. It may mean that the worst of the supply chain impact is already over, and it’s already peaked in terms of newsworthiness. And we are anticipating that that’s going to improve into next year, specifically by Q2.

Turning to inflation, we’re also seeing inflationary impacts in the portfolio. One would be from energy prices. So, obviously oil and natural gas have gone up a lot. Resin prices have risen for packaging, for example. The other place we’re seeing it in is in labor, specifically when you’re dealing with the lower end of labor. So non-unionized plants, restaurants, such as we see with Restaurant Brands [which we own], [or] for example, [the] Alimentation Couche Tarde convenience stores. And I’ll refer to this later, but generally speaking, there is a lag for pricing to catch up, so there will be an impact on margins. But ultimately, if the franchise of the business is good, they will recoup those margins over time.

The other thing I’ll mention is that looking forward, we expect to see cost inflation hit in energy and materials. Both of those supply chains have been really decimated by the collapse in pricing, particularly in energy, and costs are going to rise in those areas. So, likely the best economics, assuming a commodity price being flat, have been seen in the last couple of quarters.

MP: All right. Thanks, Steve. I just want to mention, you did mention CAE. For anybody who didn’t get a chance, we did an event with the CEO of CAE at the end of September and that’s on the Beutel Goodman website, if you’re interested in checking that out. And then just another little housekeeping thing I want to mention in terms of the format, we’re going to kind of go around the horn. So, I started with Steve, but now I’m going to turn it to Rui with the view on U.S. and international equity side.

Rui, please, your thoughts on this question?

Rui Cardoso: Sure. So, maybe I’ll give you a sense as to what we’re seeing in markets related to inflation and supply chain disruption, what it means for stocks in particular. So, the COVID downturn and dramatic rebound has really been unprecedented. Investors looking for kind of historical guideposts are not really finding any. There’s no real history here. This is quite unique to the history of the market, and this is really fueling the debate around inflation and what it means for interest rates and ultimately what it means for stocks.

So, if inflation is more transitory, then interest rates should remain low. And investors are sticking with what’s worked, which is buying growth stocks. And we’re deep into a bull market and momentum’s really taken over, and so valuation is ignored for the most part. If inflation is more persistent, more permanent, then investors are looking to hedge that by buying into cyclicals, what we view as kind of lower quality companies. [They’re] companies with lower returns, more balance sheet leverage, so a bit more financial risk. The end markets are a bit more commoditized, there’s limited competitive moat, we think. These are the kinds of stocks we tend to avoid.

And so, you probably heard a lot about this tug of war between growth and value. It’s actually more of a tug of war between growth and inflation protection, not really growth versus value. And this, in our view, is creating some hidden market risks. And investors are, in our view, maintaining valuation risk by sticking with growth. And on top of that, they’re adding quality risk by shifting over to cyclicals. And so investors are trying to mitigate inflation risk, [but] what they’re actually doing is pushing further and further out on the risk spectrum. And so, we think that’s creating some hidden market risks.

It’s been painful to kind of go through this, a lot of our stocks have been drifting. But the good news is it’s creating this great scenario where some of the best visibility cash flow businesses, some of the higher return businesses with great balance sheets – what we view as quality – are some of the cheapest stocks in the market. That’s rare to see and our portfolio is full of these types of stocks.

MP: All right. Thanks, Rui. It’s a smart way of putting it. I like that, the “tug of war between growth and inflation protection”.

Derek, it’s your turn around the horn. Give us the fixed income view, please on inflation and the supply chain issues that we’ve been seeing and what, if any, effect that’s had on how you’re operating?

Derek Brown: Thanks, Matt. So, yes, obviously, fixed income is a completely different asset class than equity, so the impact of inflation [and] supply chain disruption is different. It’s much less sector specific, it’s really more to do with the overall level of interest rates. So, we’ve had two main impacts from the persistent inflation we’ve seen this year.

The first is that bond markets globally have repriced the start to the interest rate hiking cycle. So, in Canada, for the most part, it was priced into somewhere December 2022, January 2023, and that’s kind of been shifted up about six months sometime into the summer, maybe even before [last Friday’s steeper declines in risk assets happened], into April of 2022. But that seems to be normalizing sometime in the summer. For the Federal Reserve in the U.S., the view is generally it was going to be much later than that, sometime in late 2023, and that’s been shifted up until late 2022. So, the persistent inflation has really kind of shifted up, number one, the start of the rate hiking cycle.

But counterintuitively, the other thing that’s happened is we’ve actually seen the number of interest rate hikes this cycle be reduced. The view from the market, which we tend to disagree with, is that [the] interest rate cycle will get started earlier, but because you’re hiking earlier, you’re actually going to shorten this economic growth cycle, and therefore that’s caused the curve to flatten. So, 30-year bonds have actually rallied a little bit over the past month and a bit, whereas five-year bonds have sold off. The flattening of the yield curve means earlier than expected hikes, but fewer of them.

So, we agree with the earlier than expected rate hikes. We tend to disagree with the fewer of them. The last cycle, the Bank of Canada got to about 1.75%, in the U.S., they got to 2.50%. We think these are still targets that are appropriate for this cycle. Ultimately, again, we don’t think there will be fewer rate hikes this cycle. And that’s really because what Steve and Rui were touching upon, that for the most part, we believe and we agree that inflation is transitory. The reason being is that this is supply side driven inflation, which we term and most people term as “bad inflation”.

Ultimately, it acts like a tax on consumption. If you were to think of gasoline or something like that, the price of gas goes up. So, people tend to have less money to spend on other things. So, there’s a substitution effect. It doesn’t actually increase aggregate demand. So, again, it acts like a tax, it doesn’t increase overall GDP, and also it self-corrects. This type of inflation self corrects, where people start substituting to do other things. If the prices of apples go up, people buy bananas. This is just generally how it works. Price ultimately kills price, which again causes inflation to revert from a supply side perspective.

So, will it be stickier? Yeah, it will be stickier. But ultimately, [on] interest rates, mostly what happened in the market is that you’ve seen [expectations for the] interest rate hike cycle to start earlier, but fewer of them. We would disagree with the latter part. We think it’ll be a pretty regular cycle.

MP: All right. Thank you. Stay there, Derek. I’ve got a quick follow up for you that we’re getting in the submitted questions. I think it just fits nicely here. This is with respect to the balanced portfolios. You guys are all here. But, Derek, I know that you’re on the committee.

Have you changed weights of any of the asset classes in the balanced portfolios as a result of these issues?

DB: Sure, I can answer that. So, we do asset mix differently, I think, than the vast majority of people out there. And I think rightfully so. Colin Ramkissoon is the Head of Asset Mix at Beutel Goodman, and the process has been around for a long time. How we ultimately set asset mix is from a bottom-up perspective, where ultimately the portfolio managers on the ground who are managing those portfolios kind of come up with a total return or return to target over the next three years.

This total return estimate is really what drives those mix decisions. So, we have had shifts over the past couple of years, but those have been driven really from the ground up and the bottom-up perspective of how those PMS are seeing their companies evolve or on the fixed income side, what our total return is for fixed income over the next six to 12 months. So, there have been asset mix shifts, but they’re not driven by inflation or supply chain disruptions. It’s really that bottom up, total return view of the world and it’s been very effective over the last multiple years.

MP: Okay. Thank you. Let’s move on to the next big topic, which Derek, you touched on. So, I’m just going to start with you to make things easy, I guess. And that’s, of course, about central banks. I’d call it the topic of the Millennium because it feels like that’s all that I’ve ever talked about when I was back in my media days. But anyways, we’ve now reached the point where tapering of bond purchases is underway in the U.S. It’s already complete here in Canada, all the big players around the world are basically kind of at least tiptoeing in the same direction. So, with that, Derek, let’s get you going around the horn first.

How might central bank policy at this point, and as we move into that future, change the opportunities that are available in the market?

DB: Sure. I’ll address the taper and the asset purchase programs first. We have to kind of step back and go back to March 2020 and April 2020, [when] these programs are being launched and try to put that into context. Ultimately, those programs were launched to stave off a depression. No one knew how everything was going to evolve, the virus, the vaccines, so on and so forth. So, they were enormous. They were ultimately a nuclear option from central banks. To have the Bank of Canada, who said they would never do quantitative easing, go into not just quantitative easing, but buying provincial bonds. This is “break glass in case of emergency”, and they kept breaking it over and over again to where the Fed was buying corporate bonds. So, we’ve got to put that in context and understand the amount of stimulus that was done. And frankly, it’s not necessary anymore.

We wrote a piece not too long ago, a few months ago, (Don’t Fear) the Taper, on the Federal Reserve’s upcoming taper. And that’s really what we believe, that we should not be fearing this. In fact, if anything, that the Fed has waited too long to taper. the Bank of Canada finally announced in October that they were going to stop their purchase program. And again, we thought that should have been done in the summer. And the Fed is now slowly but surely starting to recognize that they’re causing a little bit of an impact in the markets. But, really kind of more from a money market perspective, three-year bonds, five-year bond perspective, it’s not a broader risk asset impact. So, they need to not only just taper, but they’re even talking about accelerating the taper. Now, that obviously might not happen with recent events. But it is an understanding that they are having a negative impact at this point and really need to pull back on the stimulus.

Ultimately, will there be potentially higher volatility because of less asset purchases? Potentially. But there’s really going to be no material economic impact, if any, at all. So, these programs [were] needed, they need to go away. Put them away and maybe in the next recession we can talk about them. But these really were nuclear options. So, I don’t think we should expect them all to come back on board.

Then the second level of what central banks have been doing, obviously, has been cutting interest rates all through 2020. So, this is shifting in the opposite direction. Now that we’re coming out of the recession, the interest rate policies from the central banks actually will have an impact on economic growth. And so this is really what the back and forth has been. We have seen, as we mentioned before, the inflation reports have been stubbornly high. So, central banks have no choice to start prepping markets for interest rate hikes and again, we totally agree with this. It’s earlier than people expect, or the markets expected. And this has really kind of caused a little bit of a move in interest rates over the last two or three months globally.

If you think again, what central banks do, they hike interest rates generally by 25 basis points. So, when you kind of move forward interest rate hiking cycles by six months [or] nine months, this is going to have an impact on the front end of the curve, [like] two-year bonds, five-year bonds. Why the general public cares so much is [that] most mortgage rates are set off the five year or by the Bank of Canada rate on prime. So, this has really kind of caused a little bit of the headlines that you’ve seen recently, “mortgage rates are going up.” And it’s not necessarily a bad thing when it comes to where housing prices are.

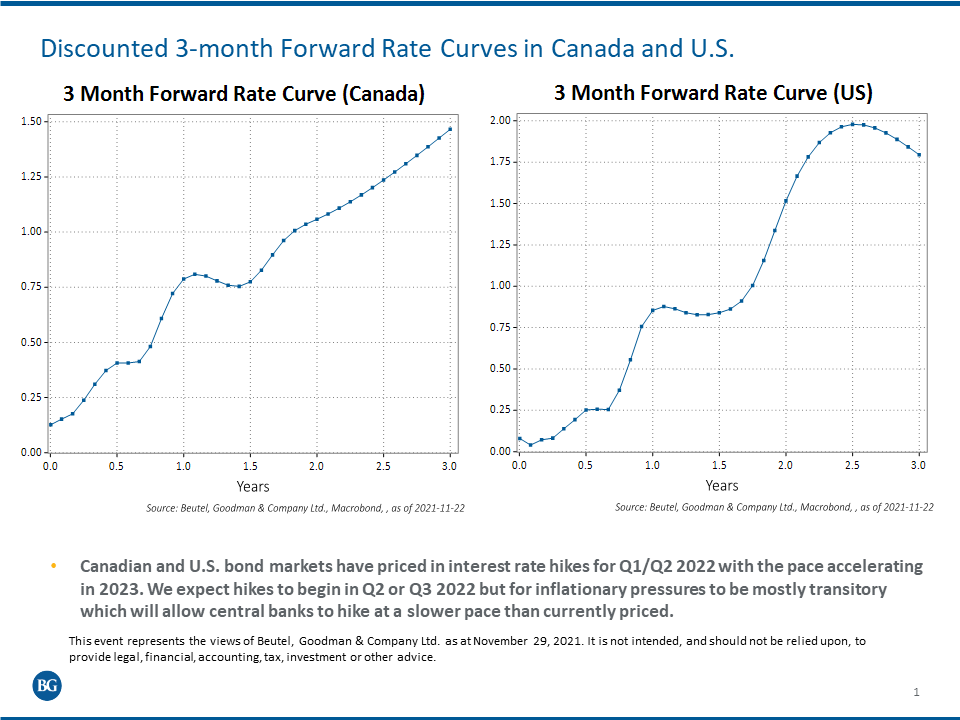

This is what central banks are trying to do. They’re trying to cause a little bit of slowing of inflation and a little bit slowing, potentially, of economic growth to slow that inflation. So, if you see here, this is what we’re kind of referring to a little bit earlier where the central bank hiking cycle on these slides here really jumped. Over the next year, they see the Bank of Canada hiking two to three times, and for the Fed to be hiking potentially four times over the next year.

But what’s interesting, again, is if you look at the right hand of each chart. The amount of interest rate hikes has actually fallen, whereas [in] Canada they’re pricing at about 1.50% to 1.75%. That was 1.75% to 2.00%, probably in April or May and in the U.S., it was about around 2.00% to 2.25%, and now down to 1.75% when it comes to total amount hikes. So just kind of reiterates what we were talking about before, where the hiking cycle will be earlier, but maybe not hiking as much. Again, we disagree with that latter half.

We do think this will be a pretty normal hiking cycle back to the 1.75% to 2.00% range in Canada and somewhere in 2.25% to 2.50% in the U.S. Again, we think [in] mid-2022 you’ll see the Bank of Canada starting to hike and maybe Fall of 2022 for the Fed. And we think recently what you’ve seen is a little bit of an overreaction to these most recent inflation prints. And they’ve really been skewed by the pandemic. And I think we have to step back again, as we’re [suggesting], and look at things in totality.

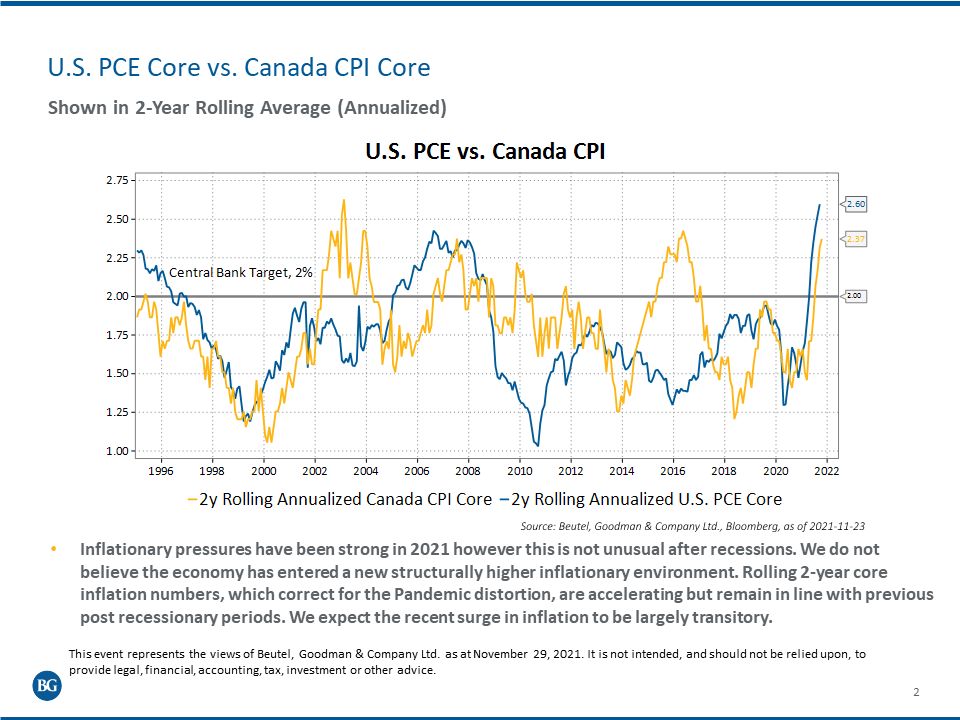

So, the next chart we have here really goes through core inflation, but on a rolling two-year level. This is our preferred measure to look at what we consider to be true inflation or sticky inflation. And again, inflation has increased relatively dramatically over the last six months. To put it in context, if you look at previous recessions, so the yellow line would be core inflation in Canada and the blue line would be in the U.S., you just think of the oil situation we had back in 2014-15. Coming out of that recession, core inflation hit about 2.4%-2.5%. It’s exactly where we are now. And then it mean reverted.

You go back to 2008, it’s something very similar, just over 2.0% [at] 2.3%. Back after the tech crisis we saw in 2000-2001, [it was the] same concept. So, coming out of recession, you get these skewed inflation data, which tends to spike on a one-year level. When you kind of look back in totality and say, let’s adjust for the pandemic effects, increased demand, the supply chain issues, [inflation] is higher and has been increasing. But it’s slowly but surely kind of within the norm of what we think.

So going forward, we expect that you’ll see inflation mean revert back down towards 2.25% level. Now, this isn’t quite where central banks want it. They want it at 2.0%. That’s their target. That was that gray line on that chart. So, we do think they’re going to be forced to hike interest rates. But again, this isn’t some sort of runaway inflation. This isn’t interest rates got to go back up to 4.00% or 5.00%. No, this is all normal. It just in the moment it doesn’t quite feel like it.

Inflation will be a little bit stickier than people think. But we don’t think long bonds in Canada – so, the 30-year [bond] in Canada is about 2.00% right now. It’s probably only going to go up about another 25 to 30 basis points. In the U.S., the long bonds are about 1.90%, so about roughly the same. They’ll get to 2.25%, maybe 2.50%. So again, 50 basis points or so higher in long bonds. That probably translates more into 50 to 75 [basis points] in [10-year bonds]. And then something similar in the five-year [bonds].

So, rates will go higher over the next two years, but not dramatically. And inflation will mean revert. In fact, we think most people will be very surprised by how quickly inflation falls down to 3.00% early next year, just because of the negative base effects we’ve created this year. So, in 2020, we had positive base effects for 2021. But high inflation prints in 2021 will detract from the number next year. So again, overall, the dislocations that we’ve seen have been a little bit of an opportunity for us to add five-year risk in the portfolio. Five- to 10-year bonds look cheap as the markets overreacted to the inflation prints, in our opinion.

MP: All right. Thanks, Derek. Steve, I’m going to come back to you. Take this question about central bank policy back to Canadian equities, please.

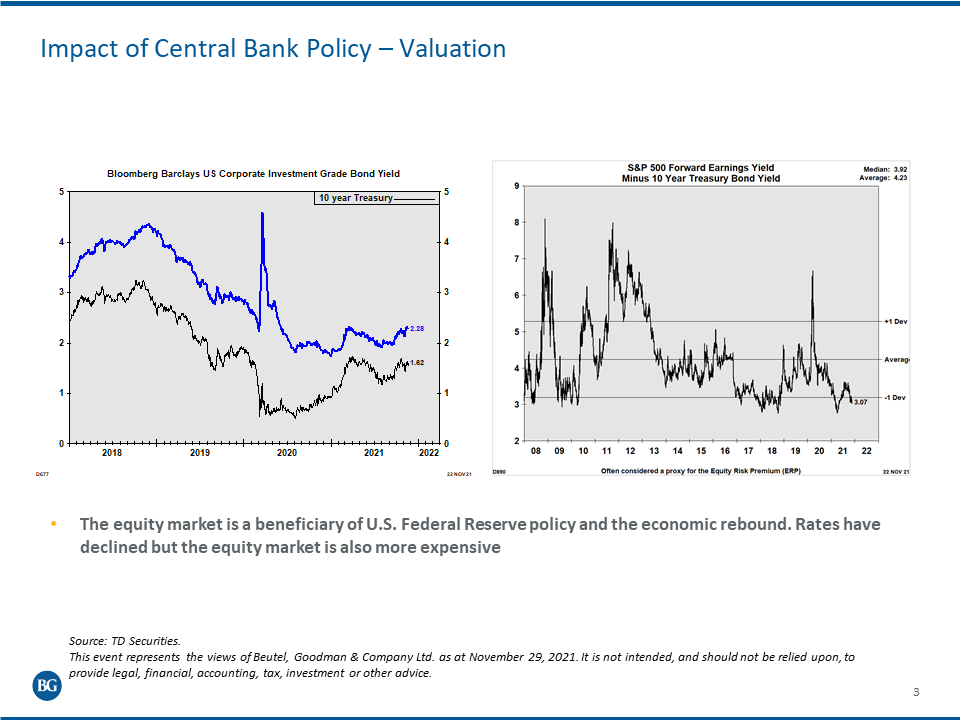

SA: Sure. Clearly, [during] this rebound in the market post-pandemic, the market did have some significant benefits from Fed policy. And most specifically, obviously, there was direct buying of the corporate market and then buying of the equity market through the prime dealers. So, if you look at the slide here the Bloomberg Barclay’s U.S. Corporate investment grade bond yield, what you can see is that corporate bonds are trading pretty tight to Treasuries. This really just indicates that there’s lots of available liquidity for corporations. But what obviously we would pay attention to, and the equity market pays attention to is 10- and 30-year bonds, as opposed to the short end.

I won’t belabour the short end because Derek’s been through it. But rate hikes are not necessarily bad news, particularly if it’s a normalization. And obviously the market is looking for significant economic growth and earnings recovery, which we’ve been seeing as Derek had alluded to. But if you look at the impact that it’s had on valuations, one way to look at that is the second chart to the right, which is the S&P 500 forward earnings yield minus the 10-year Treasury bond yield. And that’s considered a proxy for the equity risk premium.

So, you can see here that the equity risk premium is fairly low here at 3.7. The point just being is that multiples are relatively high. And we’ll talk a bit about that because there’s a dispersion of multiples in the market, which we’ll get to later. So, it’s not that the risk is uniform, but a significant rise in longer term like 10-year and 30-year bond yields would start to compete with capital for the equity market. So, I don’t think that people should think that a significant rate rise won’t start to have some impact on equities.

I kind of think it will. But the story that we’re having higher inflation and some normalization of rates and policy, as Derek talked about, that’s a relatively normal cyclical phenomenon. And frankly, if we weren’t having some of that, everybody would be concerned about what’s happening with the economy. So, in general, these are conditions that so far are still supportive of equity markets.

MP: All right, Rui, do you echo your colleagues thoughts here? Does that apply to the U.S. and international side as well?

RC: It does. And maybe I’ll bring it back to the portfolios a little and just remind people that we’re fundamental value investors on the equity side. And it’s a rigorous process for any new stock where we run very concentrated portfolios. Typically, we’re looking for 25 to 35 great companies we can own forever, and we’re very picky about stocks. It’s hard to get a stock into our portfolios, and that’s by design. And we really focus on what’s most in our control and that’s buying great franchises trading at a deep discount to intrinsic value.

We think that gives us the best margin of safety for downside protection. And we’re really looking for misguided hate where we feel like we’re firefighters running into a burning building. It’s not fun at times, but it’s part of the job. And if we could find a great company that’s misunderstood trading at a deep discount, and if they just run their business well and the market realizes how strong the franchise is, the stock can go from, let’s say, 11- or 12-times earnings to 17- or 18-times earnings. And that’s how we can get to most of that 50% or more investment threshold we require for any new position.

And so, if we need to make a macro call for one of our stock ideas to work, whether it’s, let’s say, the oil price in three years, or if we need a stock to have low interest rates and three years out for the stock to work, we know that’s out of our control. And there’s so many decisions in a decision tree moving from a call on inflation to a stock call, we need to get most of them right. Once you start getting one or two wrong, your probabilities on the stock collapse to zero.

So, if you think of the inflation call, what that means for interest rates, what that means for the economy, what the economy means for the stock market, because the economy and the stock market can be on completely different cycles. And then within the stock market, which stock market, and then what sector? And then ultimately, which stock? There are so many decisions we’d have to get right there. We’re going to get a few wrong. And so, we really focus on the bottom-up fundamentals. If the companies can execute well, the valuation should correct and that’s where we get most of our upside. So, we don’t really take macro inputs into our key stock decisions.

However, when the market gets overly focused on a macro issue, it does create opportunities. One more recent example is drug pricing in the U.S. always tends to come into focus around elections in the U.S., and the drug companies can trade down as a group, the pharmaceuticals. But the long-term dispersion in returns is quite dramatic. And so, when they trade down as a group based on some kind of macro issue or macro view on drug pricing, it gives us the chance to be very selective, choose the most innovative companies, most focus on certain specialties, and we can make a very much bottom-up driven call and take a long term perspective on that stock.

MP: Thanks, Rui. And it’s a great reminder too [about] just how the BG process works. I think discipline matters so much, and you really kind of highlighted that there the importance of it, but I have to stay disciplined in my role here and keep the ball rolling. So, Rui, you finished the last one we haven’t started yet. So, I’m going to make you start this time.

Our final major question here is, how are valuations impacting the positioning of your portfolio?

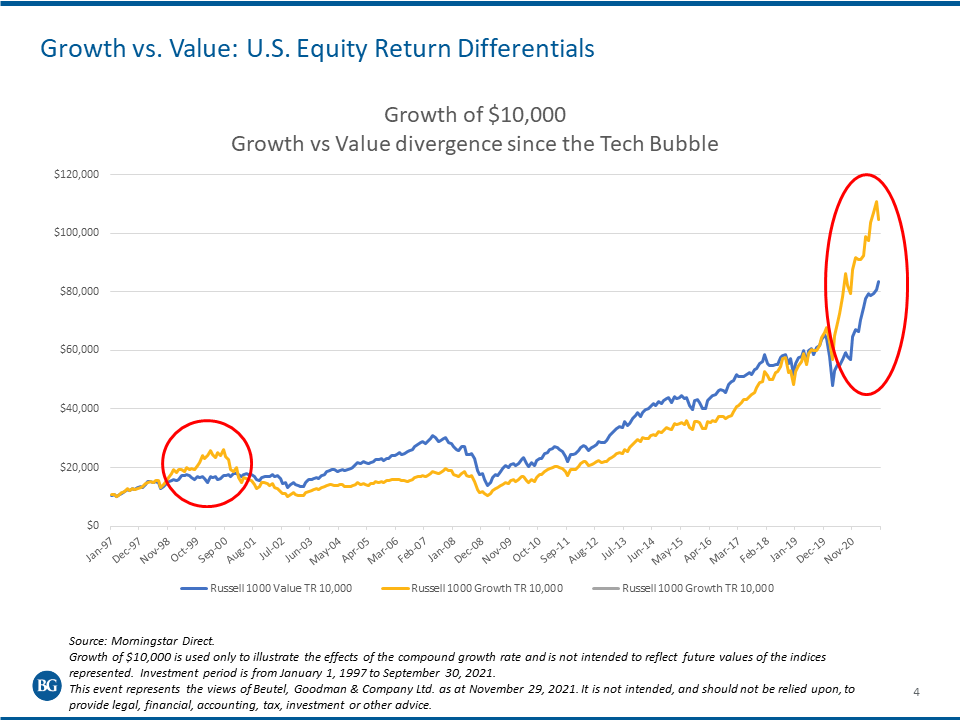

RC: Sure, it’s important to point out that as value investors in the long term, we think the value wins out. There’s long stretches of time where valuation doesn’t matter. But in the long term, valuations always matter. And so, when we look at how valuations have done historically, we look at growth versus value over the long term, and we use the Russell 1000 Value [Index] as the benchmark here because it’s much deeper on the growth versus value side. And there’s better historical data. And there’s really two periods where growth has actually won. The rest of time, value has actually won out.

And those two periods were the late 1990s to the 2000 period, and then the tech wreck happened. So not a very good ending for growth. And then more recently, since near the end of 2018 until now, growth valuations have really stretched out, and growth has done much better than value. But over the long term, in our view, value still wins out. We don’t know what the catalyst is to drive valuation back into the picture, but we know we should maintain our focus on downside protection because over long-term valuations will matter.

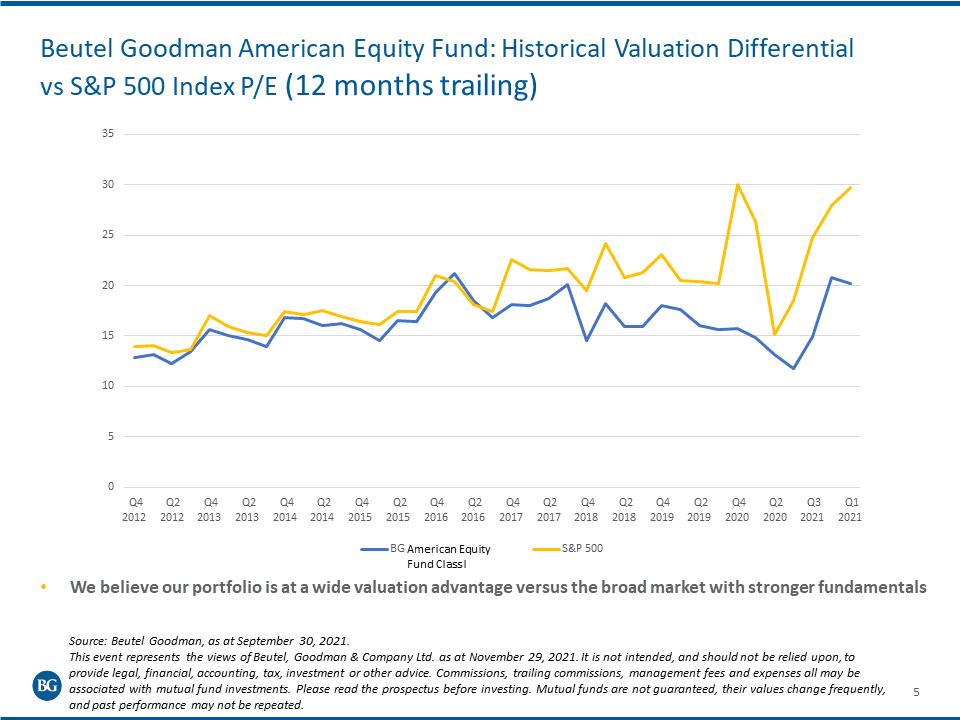

And so, as I mentioned before, there’s a kind of tug of war in the market between growth and cyclicals, and that’s left a lot of our value stocks out in no man’s land. Our stocks have drifted versus the market. They haven’t done poorly, but the market’s really taken off. And so typically, what we’ll see in our portfolios is that they tend to have higher quality, better return on equity, lower leverage, more financial flexibility, less balance sheet risk, better dividends than the market. And our portfolios tend to trade slightly cheaper than the market, so better quality at a lower valuation.

What we’re seeing more recently is that the valuation gap between our portfolios and the market has really widened out, really going back to 2019 or so when it really widened out. And so that’s going to close in a couple of different ways. Hopefully, it’s our portfolio is getting closer to the market rather than the market coming down. But I think in the long run, we’re still very confident in the downside protection capability of the portfolio. And it seems to us that markets are really focused on missing out, and there’s very little focus on downside protection. And so, it’s really one of the core tenets of our investment philosophy trying to limit the downside per stock in our portfolios. It’s done well for us historically, we’re quite confident in that going forward.

MP: All right. Thank you. Rui. Steve, I’m going to ask you to bring it back to Canada, please.

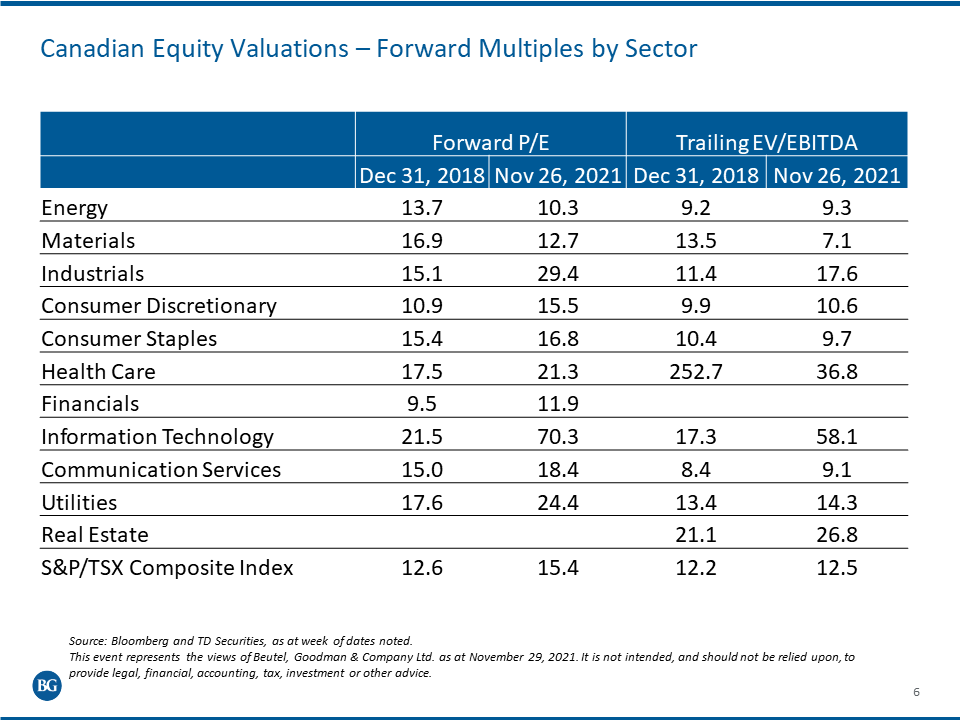

SA: Sure, Matt. We have a slide here that looks at multiples in 2018 versus today. Now, again, we’ll use earnings as a proxy for free cash. They’re not the same, but the other multiple we’ve put up here is trailing enterprise value to EBITDA. And that’s just to show that the conclusions that we’re drawing are represented at a firm level from cash flow as opposed to earnings. So, I think there’s a couple of observations you can make when you look at this. Two areas of the market that look relatively expensive are industrials and information technology.

Now, in the case of industrials, it’s very company specific, and we own quite a few industrials. And one of the things is that a lot of the earnings in this area really are just coming out of the cycle now. And so you’ve got areas like airlines, for example, that have been challenged, and we’re expecting that there’ll be quite an improvement in the profitability of many of these companies. So, we’re seeing some selective opportunities definitely there.

The other area that sticks out is information technology, which Rui has touched on a little bit. So, this is Canada specific. But you’ll see that [with] valuations, the story of the COVID downturn was clearly that there were some positive implications for information technology. We had an increase in things like online shopping. We’ve also had a continued push into the cloud. But notwithstanding those secular factors, the big driver on top of earnings growth was multiple expansion, and there’s been dramatic multiple expansion. These are multiples that we haven’t seen for a long time in the market, reaching back to the 2000s. And there’s certainly a fair bit of concept activity going on in IT as well.

So, IT looks expensive. But it’s been a challenge because it’s been acting relatively defensively through the pandemic, because the earnings were a lot more defensible than other areas of the market that were more tied to GDP. And there were these secular changes. But I think what people are disregarding is the multiples have also expanded dramatically, and the idea that this area will be defensive reflexively may not hold up if valuations prove to matter, which they generally always have.

A couple of other observations outside of IT looking expensive. Energy in Canada looks a little bit inexpensive. We think that the commodity rally has largely been priced in for both oil and gas. Lower valuations than history may be a product of a few things. One is we don’t have anywhere near the international capital flow that we did earlier in the decade. Another is potentially ESG and concerns around longer run oil demand into the [2027 to 2030 timeframe] because we’ve seen the impact of declining demand on pricing. And finally, growing production in Canada is difficult because we do have significant egress issues, particularly with the cancellation of [the Keystone XL pipeline]. So, the companies are trying to produce what they are and have some modest growth. But certainly, large growth projects are going to be a lot harder to do.

Financials look normal, and valuations are generally attractive. This is in Canada, and we view Canadian financials as being very high quality, with a good source of dividend yield, and they’ve tended to be market or overweight in our portfolio.

Utilities and real estate are going to be impacted most by rates rising at least the most directly and quickly. We have added some utilities in the downturn and certainly would view it as an opportunity to add high quality utilities. In particular, there are examples of companies where they’re tending to benefit from the growth of transmission and electrification.

So, beyond all of these general comments, really, these valuation gaps will continue to exist and provide us an opportunity to continue to upgrade the portfolio. But remember, our focus is on a discount to the intrinsic value for these businesses and really understanding their quality and having certainty around future free cash flow generation. So that is what we’re seeing in the market, which is to say a market that’s generally expensive but has some areas being more acutely expensive than others that are less. And there is a certain bifurcation of the market that’s occurring. And we do expect that valuation will matter at a point

MP: “Bifurcation” – word of the day. Derek, that’s more of an equity question, I know, when it comes to valuation, but I’m not going to let you get away with not saying anything.

Derek, tell me your thoughts on the valuation equation at this point.

DB: I’ll try to limit that to corporate bonds because it’s very different in fixed income. It’s definitely apples and oranges between fixed income and equity. Overall, corporate bond spreads are relatively tight. They’re through their long-term averages, but rightfully so. Economic growth looks pretty strong this year and into next. Yes, we talked about rates going higher and inflation being higher. But again, I think Steve used the right word: normalization of activity. This is what’s happening, and the market is pricing that in on a corporate bond side.

And so yeah, overall, there are some opportunities, not a ton of them. But there are some. We like financials, much like the Canadian equity group as well, for different reasons. We don’t particularly care about the dividend growth, but we really like the franchises and the strength of the balance sheets and things like that. So, a big fan of Canadian banks right here.

We also see certain mandates that we’re allowed to use high yield bonds in. We see some value in those as well, specifically in what’s known as rising stars or crossover bonds. These would be companies that are potentially too small to be considered investment grade or on their way there or have a little bit too much debt on their balance sheet. And they’re working through that. There’s a couple of companies out there. Videotron is a good example. [Parent company] Quebecor, they’re just kind of busy building their franchise. What’s going to happen with the Shaw acquisition? No one really knows Rogers buying Shaw and the divesting of assets. So, they’re not investment grade, but a very strong company. We like them a lot.

There are a few other companies like that out there. So once those companies move their way to investment grade, there’s generally some pretty good value. We’ve kind of entered a credit pickers’ market, for lack of a better word, where the credit team has to do a lot of due diligence, pick and choose the winners over the next little while and the companies that are improving. So overall, we like financials, and we like kind of name-specific companies as well.

MP: All right. Thank you. We’ve got a bunch of questions that have come in, and I see that we do have a little bit more time. So, I’m going to keep you guys with your feet to the fire with some of these questions. Steve, I’m going to start with you. Some of these questions I know we’ve touched on, but obviously our clients and audience members want to probe a little bit more.

One of the questions here, Steve, for you, how do you project cash flow when the last two years have been abnormal and costs are likely to rise?

SA: Matt, projecting cash flow is always something that is company specific. And the biggest abnormality that’s happened in this cycle has been that consumer durable spending is way up. And that’s one of the things that’s causing a lot of the challenges in the supply chain. And we’re also, of course, seeing the other question, which is the impact of inflation and energy prices on companies.

One company that dealt with a lot of these kinds of pressures a few years ago was Metro Richelieu, which we bought in 2016/17. And that was when there was some inflationary pressure. But there was also big pressure on wages because we had significant minimum wage increases, specifically in Ontario. So, what you saw there is that ultimately they were able to reprice and recover the margin. And it turned out to be a really good buying opportunity. So, I think the thing to remember is that it kind of goes back to what Rui was talking about. There’s a lot of factors in the market. What it really comes down to is your confidence in the future free cash flow of the business, and a lot of that has to come down to the quality and the actual defensive moat around the business.

And then when you get a substantial discount, you let that business work for you, so you’re able to buy it at a discount. And ultimately, usually the company can manage through that. Now it’s not always going to work, but your odds go up a lot when you have high quality businesses that are less impacted by some of these factors, which are really, frankly, out of our control as well. So, every time you’re dealing with a company, the projections are really company specific, and we have to inform ourselves because we would agree with the question, which is that the idea that this has been a fairly abnormal period over the last couple of years. I mean, nobody would say it is normal. So, we’re going to have to use our skill to understand what we think normal looks like in the future.

MP: That sounds very philosophical. What is normal? One more question. I’ve got time for one more question. Rui, I’m going to pose this one to you. Steve touched on it earlier, but the audience wants to expand the view, if you will.

So, the question reads, if equities are overvalued at present, what is the view on which countries or which industries may be most overvalued?

RC:Sure. Steve highlighted technology globally as a sector that seems the most overvalued. Tech is actually around 30% of the S&P 500 now, and that doesn’t include Google, Facebook, Netflix, Amazon or Tesla. All those stocks are now classified in different sectors, whether it’s communication services or discretionary. what we would traditionally call tech is actually much bigger than that 30% of the index. And it’s a sector where valuations are factoring in the highest long-term growth, and you have to sustain that over very long periods. That’s very hard to do, which leaves very little room for error. So, there’s no doubt there are great businesses, but a lot is priced in.

And I also remind everyone that we’re very much bottom-up stock pickers. We actually don’t make sector calls, and there’s a natural rotation that happens within our portfolio. So, looking at tech in particular, we own a lot of tech stocks, and we owned them when they were out of favor. And now as momentum has really kicked in, as these stocks work, and they go through our target prices, we automatically sold a third when a stock was to our target. And then we review and if it’s fully valued when we set a new target, we exit that position. And so, we had a lot of weight within technology and the weight has been shifting out of technology as the number of holdings like TE Connectivity and KLA Tencor became fully valued, and we exited those positions. And now we’ve been shifting to other sectors where we see great quality at a deep discount. I mentioned Pharmaceuticals, consumer staples is a sector as well [where] we see great value.

MP: All right. Thanks, Steve, Rui. Derek, I would really love to pepper you with one more question, but I’m running out of time, so I’m sorry that’s all the time we have for, unfortunately. But I do want to say thank you to everybody who dialed in. We had a great turnout. And that’s wonderful. Steve, Derek, Rui, thank you for sharing BG’s views on these important topics. Hearing your expertise is always fantastic for me personally, it’s a learning experience. I feel smarter.

If we didn’t get to your question and there are a couple of open questions still, that we just don’t have the time for. We have the list of who submitted questions. We’ll be following up with you, so we won’t leave you hanging. And if anybody else has further questions or feedback, please do not hesitate to reach out to your relationship manager or your regional director, whoever your contact at BG may be.

Just finally, as a reminder, this event represented the views of Beutel, Goodman & Company as at today’s date, November 29, 2021. It’s not intended and should not be relied upon to provide legal, financial, accounting, tax, investment or other advice. And this was not an invitation to purchase or trade any securities. Beutel Goodman does not endorse or recommend any securities that were referenced in this presentation. Thank you all for tuning in and have a great day.

Related Topics and Links of Interests

- Beutel Goodman Speaker Series: In Conversation with CAE Inc.

- China’s Slowdown: An Aging Dragon Can Still Breathe Fire

- (Don’t Fear) the Taper

- Beutel Goodman Mutual Funds

©2021 Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd. Do not copy, distribute, sell or modify this transcript of a recorded discussion without the prior written consent of Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd. All information in this transcript represents the views of Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd. as at the date indicated.

This information in this transcript and recording is not intended, and should not be relied upon, to provide legal, financial, accounting, tax, investment or other advice.

Certain portions of this commentary may contain forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements include statements that are predictive in nature, that depend upon or refer to future events or conditions, or that include words such as “expects”, “anticipates”, “intends”, “plans”, “believes”, “estimates” and other similar forward-looking expressions. In addition, any statement that may be made concerning future performance, strategies or prospects, and possible future action, is also forward-looking statement. Forward-looking statements are based on current expectations and forecasts about future events and are inherently subject to, among other things, risks, uncertainties and assumptions which could cause actual events, results, performance or prospects to be incorrect or to differ materially from those expressed in, or implied by, these forward-looking statements.

These risks, uncertainties and assumptions include, but are not limited to, general economic, political and market factors, domestic and international, interest and foreign exchange rates, equity and capital markets, business competition, technological change, changes in government regulations, unexpected judicial or regulatory proceedings, and catastrophic events. This list of important factors is not exhaustive. Please consider these and other factors carefully before making any investment decisions and avoid placing undue reliance on forward-looking statements. Beutel Goodman has no specific intention of updating any forward-looking statements whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise.