Summary

Tariffs have been the major theme affecting markets so far in 2025. In this piece, the Beutel Goodman Fixed Income team explores recent trade announcements and examines what they may signal about the potential direction of future trade policy and the macroeconomic environment.

By Beutel Goodman’s Fixed Income Team (as at April 30, 2025)

The first 100 days of the second Donald Trump presidency have passed, and it is clear we have entered a new era for global trade. The events of “Liberation Day” on April 2 underscored this, with the U.S. government introducing a 10% global baseline tariff, as well as higher reciprocal tariffs targeting countries with large trade deficits with the United States.

This announcement caused significant volatility in securities markets. Amid the fallout, the Trump administration announced a 90-day pause on the reciprocal tariffs for most countries (the 10% tariff baseline will continue). China, in contrast, received no such concession. Rather, the U.S. government increased levies on Chinese imports to as high as 145%. China responded in kind, with tariffs of 125% on U.S. goods.

Although risk markets were buoyed by the pause, the average global effective tariff rate remained largely as-is after the 90-day pause announcement, and levies were maintained on specific targeted industries such as steel and aluminum.

Those targeted industries are an important part of Canada’s exports into the U.S., but as USMCA-compliant goods are exempted from tariffs currently, Canada’s average effective tariff rate stands at approximately 5-7%, which compares favourably to the terms imposed on most of the rest of the world.

Tariffs Take Hold

Based on our analysis, we can narrow down the U.S. administration’s approach to tariffs to the following objectives:

- Negotiation Tool

- Revenue Generation

- Protectionism of Industry

Using tariffs as a negotiation tool to gain concessions from global trading partners appears to be the most immediate objective of the U.S. government — it is also the one securities markets and media have mainly focused on. The administration has noted that its objectives include fighting economic practices it deems unfair, including VAT (value-added tax) taxes, trade restrictions, currency manipulation and intellectual property concerns, as well as border security.

These latest tariff policies have been enacted by executive orders under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977 (IEEPA). Framing the tariffs as a necessary tool to negotiate national security objectives has allowed the U.S. administration to bypass congressional approval and enact the tariffs immediately, while furthering some of its other goals.

The negotiation tactic approach also has the effect of normalizing the concept of tariffs and creating greater scrutiny of global trade policies. In contrast to the eye-watering individualized reciprocal tariff levels announced on “Liberation Day”, a 10% base-rate has been normalized to seem benign. This has opened the door for greater acceptance of a policy of a permanent relatively-low-level tariff rate. This is important because the concept of permanent tariffs is relevant to meet objectives #2 (revenue generation) and #3 (protectionism of industry).

Without permanent tariffs, there would not be enough time to generate sufficient revenue for the U.S. government so as to have a meaningful impact. The U.S. government has a debt and deficit problem, with interest costs representing 13% of total outlays or US$881 billion as of fiscal year-end 2024 (source: CBO, as at January 17, 2025). Left unchecked, the U.S. Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that by fiscal 2035, interest expenses will grow to US$1.78 trillion per year (source: CBO, as at January 17, 2025).

An increase in tariff revenues could offset some of the ballooning deficit or pay for anticipated programs such as personal and corporate tax cuts. The next question would then be at what level should tariffs be set to raise maximal revenue?

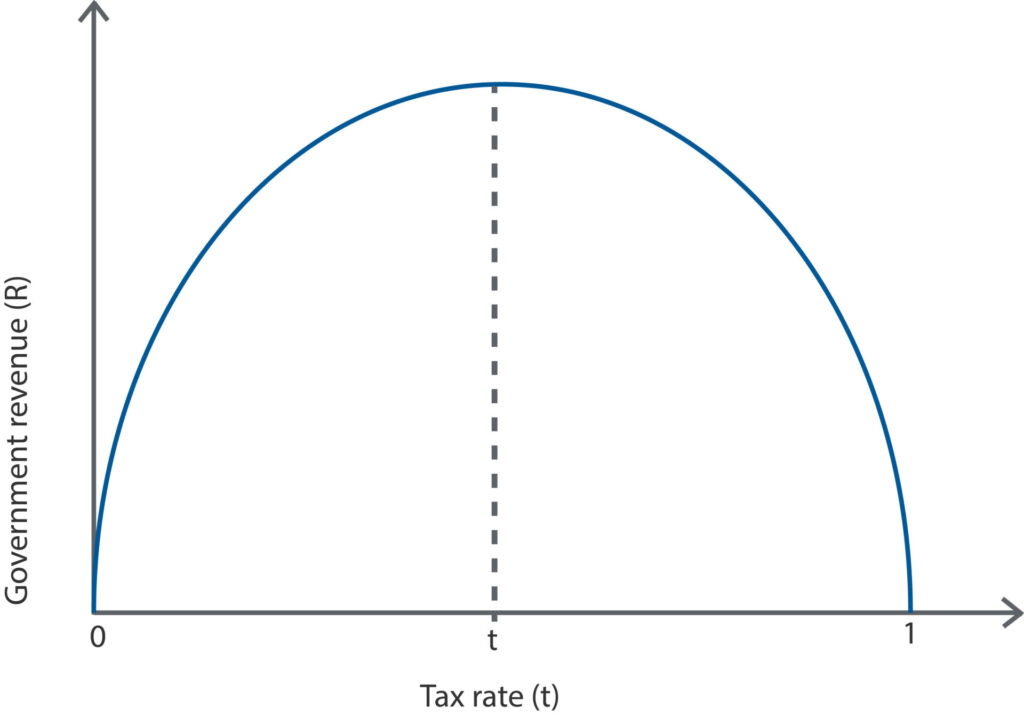

The Laffer curve is a common tool economists use to measure the relationship between taxation and resulting tax revenues for governments and applies here in terms of tariffs. According to the Laffer curve, revenues will be highest when tariffs are not set so high as to reduce the volume of goods being imported.

Exhibit 1: The Laffer Curve.

This chart shows the relationship between tax rates and government revenue. Revenue rises with higher tax rates up to a peak, then declines as tax rates approach 100%, illustrating the idea that excessive taxation can reduce total revenue.

Following this reasoning, the current 10% global tariff rate is likely to be maintained, which would raise approximately US$350 billion a year if the US$3.3 trillion (2024’s total) in annual goods imports continues (source: CBO, as at January 17, 2025).

Permanent tariffs are also relevant to the third objective, protectionism. Permanence can also be a resolution to the uncertainty that has prevailed over the recent past.

Reconfiguring supply chains, by switching suppliers, retooling factories or building out new production facilities, generally takes a considerable amount of time. If tariffs are expected to be temporary, companies may be unwilling to bear the costs to undertake such an exercise and therefore the anticipated onshoring of manufacturing may not come to pass.

In addition, companies need to be able to properly project the economics of reworking their business models before making any supply chain decisions. Some level of certainty around future tariff policy will be required for businesses to analyze the impact of paying tariffs on one hand, and the cost benefit of onshoring supply chains to the U.S. on the other hand.

Furthermore, to incentivize companies to keep their businesses in the U.S., tariffs must be set high enough for the economics to favour those initiatives. We estimate that based on historical precedent, for capital-intensive industries, a 10% tariff may be too low to incentivize onshoring. A more punitive tariff of 25% or more may be needed to further the goal of protectionism for U.S. industry.

Putting this analysis together, in our view, the first objective of tariffs as a negotiation tool is running counter to the third objective of protectionism, because it requires a resolution of the uncertainty created by these tactics. This implies that the ultra-high tariffs on certain sectors/geographies will have a limited shelf life in terms of usefulness and are mostly noise with respect to our longer-term investment horizon. The second objective of tariffs as a revenue generation tool implies that a 10% baseline global tariff is likely to become permanent. Since this 10% level may not be enough to prompt the reconfiguration of supply chains in capital-heavy sectors, we anticipate that higher tariffs (25% or more) on certain industries of particular national interest may remain under this government.

Tariffs and the Macro Environment

According to the U.S. Treasury, the U.S. raised an estimated US$17 billion in tariff revenue for the month of April, but it remains unclear who is bearing this cost. The impact depends on how much of the tariff is paid by the exporter or the intermediate producer (by reducing their margin) and how much is being passed through to consumers by increased prices, thereby driving inflation. At the same time, heightened tariff-related uncertainty is weighing on business and consumer confidence, which could slow economic growth if it persists.

The scenario where prices are rising and the economy is slowing is known as stagflation. This unusual phenomenon was prevalent in the 1970s and 1980s when economic growth was largely anemic, unemployment was high, and inflation soared to over 10%. The stagflationary backdrop then was due to several different factors, including a severe oil price shock of over 400% caused by an OPEC oil embargo and a wage price spiral brought on by cost-of-living adjustments made to a heavily unionized workforce.

While tariffs may dampen growth and push prices higher, a repeat of 1970s-style stagflation appears unlikely. Energy prices are contained, and low unionization reduces the risk of a wage-price spiral. Instead, a “stagflation-light” scenario — with inflation around 3%, relatively close to central bank targets — seems more plausible at this point than a return to double-digit inflation.

Given the dampening effects of tariffs on consumer demand and broader macroeconomic conditions, we also see a resurgence of post-COVID high inflation levels (>8%) as unlikely.

The potential reduction in demand can be understood through the lens of consumer spending power, which draws from past savings, present income, and future borrowing. Post-pandemic savings are largely depleted, with the personal savings rate near historic lows in the U.S. (source: St. Louis Federal Reserve). Present income from employment wages may weaken as firms facing margin pressure curb wage growth, while tariff-driven inflation also erodes purchasing power. Future spending via borrowing is constrained by tighter financial conditions.

This downward pressure on consumer spending power could lead to a reduction in aggregate demand for goods and services. If the tariff-driven supply disruption occurs at the same time as demand falls, inflation may not materialize, resulting instead in lower sales. The ability to pass through price increases to the consumer is always contingent on demand, which is why companies can generally manage margins rather than profits.

Over the long term, however, a reversal of globalization and reduced interdependence and integration between countries due to trade barriers and tariffs could raise production costs, leading to higher inflation, while also weighing on global growth and productivity.

Looking at recent economic data, we believe it is still too early to know if a recession is in the cards. We are seeing some signs of “stagflation-light” in some of the soft data (consumer confidence surveys are a common example of soft data, while hard data may be an official jobs, GDP or inflation report from a government agency), as business and consumer confidence have been hit in recent months.

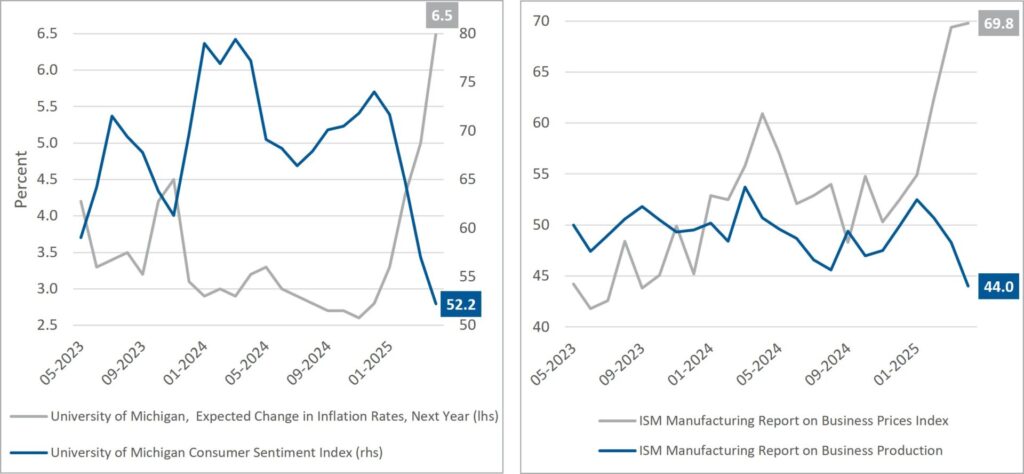

Exhibit 2: Stagflation-light in soft economic data.

The chart on the left shows University of Michigan survey data since the beginning of 2023: the Consumer Sentiment Index is at lows and the Expected Inflation Rate Next Year Index is at highs. The chart on the right shows Institute of Supply Management Manufacturing data over the same period: the Business Production Index is at lows and the Business Prices Index is at highs.

January 1, 2023-April 30, 2025.

Source: Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd., University of Michigan, Institute for Supply Management.

The impact of tariffs on certain key Canadian sectors such as autos, metals and aluminum may leave the Canadian economy more vulnerable to a recession, absent significant fiscal intervention from the government. We are still waiting to see the extent of the impact on hard data; however, the unemployment rate is still relatively low, retail sales have been strong, and credit card spending has still been holding up, but we are monitoring data releases closely for tariff impacts.

Outlook

Looking ahead, it is our view that the impact of tariffs on global GDP growth and inflation is likely to be somewhat mismatched, leading to the following impacts:

- The first order impact: Tariffs raise prices, resulting in both inflation and increased inflation expectations.

- The second order impact: Due to inflation, central banks cannot cut interest rates to stimulate the economy as soon as they would typically.

- The third order impact: Higher interest rates eventually lead to lower growth and lower inflation.

We expect the impact on GDP may be staggered. First, we expect a rotation in discretionary spending, away from categories like airlines and travel toward staycations and lower priced retail options, and eventually to a more broad-based decline in spending activity, should employment also slow. If there are increased job losses, then we may see negative reflexivity or a “snowball effect” where job losses lead to lower demand for goods and services, which ultimately leads to a recession. That scenario is still hypothetical at this point as people generally are still employed and spending in the U.S. and Canada.

Focusing on Canada, and flipping the script somewhat, our current outlook is not as bearish as the market consensus. Although Canada is an export economy, with high reliance on U.S. trade, it is well positioned in a global context since its effective U.S. tariff rate (approximately 5-7%) is lower than the global average. Its energy sector, meanwhile, has largely been immune to the tariffs through USMCA exemptions. In addition, there is limited scope for the U.S. to find a substitute for Canadian heavy crude oil for U.S. refiners.

From a fiscal standpoint, the federal government and its provincial counterparts have expressed a willingness to unleash fiscal stimulus if needed. Despite this, it is important to note that should the U.S. enter a recession, Canada is likely to follow.

We expect growth will eventually slow and with that, lower interest rates, but the timing may be lagged because of the first order impact on inflation and inflation expectations, which may keep short-term yields elevated. This environment may result in a flatter yield curve in the near term as central bank inflation fears may mean they are unable to reduce policy rates.

As long-term investors, we will remain focused on the fundamentals, as well as where we are in the ever-evolving market cycle.

Download PDF

Related Topics and Links of Interest:

©2025 Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd. Do not sell or modify this document without the prior written consent of Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd. This commentary represents the views of Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd. as at the date indicated.This document is not intended, and should not be relied upon, to provide legal, financial, accounting, tax, investment or other advice.

Certain portions of this report may contain forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements include statements that are predictive in nature, that depend upon or refer to future events or conditions, or that include words such as “expects”, “anticipates”, “intends”, “plans”, “believes”, “estimates” and other similar forward-looking expressions. In addition, any statement that may be made concerning future performance, strategies or prospects, and possible future action, is also forward-looking statement. Forward-looking statements are based on current expectations and forecasts about future events and are inherently subject to, among other things, risks, uncertainties and assumptions which could cause actual events, results, performance or prospects to be incorrect or to differ materially from those expressed in, or implied by, these forward-looking statements.

These risks, uncertainties and assumptions include, but are not limited to, general economic, political and market factors, domestic and international, interest and foreign exchange rates, equity and capital markets, business competition, technological change, changes in government regulations, unexpected judicial or regulatory proceedings, and catastrophic events. This list of important factors is not exhaustive. Please consider these and other factors carefully before making any investment decisions and avoid placing undue reliance on forward-looking statements Beutel Goodman has no specific intention of updating any forward-looking statements whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise.