By Beutel Goodman’s Fixed Income Team

We are approaching the tail end of the 2022 FIFA World Cup, which looks to have secured a podium finish in the competition for most controversial sporting events ever held. Qatar’s suitability as a host has been debated endlessly for more than a decade now, casting a large shadow over the tournament and the efforts of the world’s best players.

On the field, there have been some real surprises, including Morocco confounding expectations to reach the semi-final stage, but World Cups usually have an air of inevitability about them. No team outside of South America or Europe has ever won the competition, and only eight different teams have taken home the trophy in the 21 times it has been contested.

There are no sure things in life or football, but it’s a safe bet that one of the traditional football powerhouses will ultimately prevail when all is said and done on December 18. We can make that assumption because history tells us that is what usually happens.

Accurately predicting where the economy or securities markets are headed is a lot more difficult, however. History does offer some guidance, but we find ourselves facing a unique set of circumstances as we bid adieu to 2022.

A Different Kind of Cycle

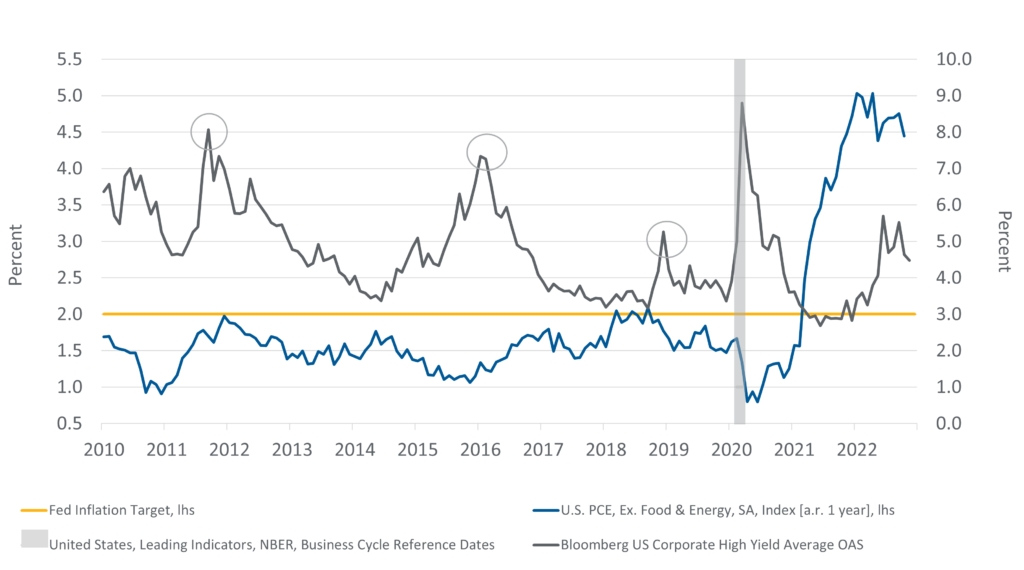

In assessing the investment environment, it’s important to remember the difference between credit cycles and economic cycles. A credit cycle is a period when borrowers’ access to credit and the cost of credit changes, based on prevailing financial market and liquidity conditions, while economic growth continues upwards. Recent examples of this occurred in 2012, 2016 and late 2018/early 2019 (see Exhibit 1). In each of these cases, significant monetary easing by central banks helped credit conditions, injected liquidity, and prolonged the economic cycle. That likely won’t be repeated this time round; given the global fight against inflation, an easing of monetary policy isn’t a realistic option for central banks until prices start to come down on a sustained basis.

Exhibit 1. This Time is Different. This line graph shows credit spreads widening during the three highlighted credit cycles (2011, 2016 and 2018) were not associated with above-trend inflation, which is the case now.

Source: Beutel Goodman, Macrobond, U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), as at December 7, 2022

The end of an economic cycle is marked not only by a decrease in overall economic output (negative GDP), but perhaps even more importantly, by economic slack created through an increase of more than 1% in the unemployment rate. Since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), central banks have regularly cut interest rates and launched asset purchase programs to promote credit growth and help the labour market whenever they deemed necessary. This monetary stimulus was feasible because inflation remained close to the central banks’ 2% target rate. The opposite now holds true, and entrenched inflation is central banks’ primary goal; unfortunately, it appears that the only way to ensure lower inflation is to trigger an end to the economic cycle.

The limits of central banking in stimulating the economy through open-ended liquidity injections have now been reached, as we saw with the Bank of England’s (BoE) intervention to support the U.K. bond markets in September. In that instance, monetary stimulus was short and sweet, and the BoE quickly returned to its original plan of quantitative tightening. A major development to watch out for in 2023 is how markets react to the realization that monetary stimulus is unlikely to be there to protect the value of risk assets in a correction.

Anemic Growth Predicted for 2023

Looking at growth, liquidity and valuation levels, it seems that central bank predictions at the beginning of this year for a soft landing (à la 2012, 2016 and 2018/2019) were wishful thinking as we approach the end of the economic cycle. With central banks worldwide already engaged in quantitative tightening, there is much less liquidity in the system, while valuations and growth projections are being revised downward.

In Bloomberg News’ November Economic Forecast Survey, Canada’s economy is predicted to expand by 3.3% in 2022, 0.6% in 2023 and 1.7% in 2024. The U.S., meanwhile, is forecast to expand by 1.8% in 2022, 0.5% in 2023 and 1.4% in 2024.

Canada’s growth this year can be attributed in large part to the strength of its Energy sector, which has benefitted hugely from high oil prices. The war in Ukraine, in taking Russian oil off the table for many western nations, has been a boon for other producers, and it appears that conflict is likely to drag on for the foreseeable future. A prolonged conflict could continue to support higher oil prices, but a global economic downturn will likely have the opposite effect, as we saw when OPEC recently cut its forecast for global oil demand for 2022.

Answering the Inflation Question

Inflation has been the major investment story of 2022, but it is too early to say whether central banks’ series of hikes are having the desired effect in bringing prices under control. Canada’s Consumer Price Index (CPI) reading for October (year over year) of 6.9% mirrored the September number, with a drop in grocery prices offsetting an increase in gas prices.

Excluding food and energy, prices rose 5.3% year over year in October, a slight decrease on September’s 5.4% core number.

In the U.S., the CPI rate slowed for a fourth month in a row to 7.7% in October, representing the lowest year-over-year CPI reading since January, and comparing favourably to the 8.2% reading in September. The core figure for October was 6.3%, down from 6.6% in September.

These CPI numbers, while an improvement, are still a long way off both the U.S. Federal Reserve’s (Fed) and the Bank of Canada’s (BoC) target rates of 2%, so the prospect of a rate cut by either institution appears a long way off. Central banks will first need to see a reset in inflation expectations by consumers and businesses, as well as a meaningful and sustained downturn in inflation rates before declaring victory.

Following the Fed

It’s expected that both the BoC and the Fed will raise rates again in their December meetings. Bond markets are currently pricing in a terminal rate of 4.25%–4.5% for Canada and 4.75%–5.0% in the U.S. The difference can be attributed in part to high consumer debt levels and vulnerabilities in Canada’s housing market, which makes up a significant portion of total GDP (6.63% of GDP in real terms as at Q3/2022, according to Statistics Canada). The preponderance of five-year mortgages in Canada makes its economy much more sensitive to higher rates than the U.S., where thirty-year mortgages are commonplace. If homeowners are paying more to service their mortgages, that money won’t be spent elsewhere in the economy, lowering overall economic output and consumer confidence.

Just as Canada preceded the U.S. out of the World Cup, it may also be the first to stop hiking rates. The BoC has already raised rates by 3.5% (to 3.75%) so far in 2022, and another hike of 25 to 50 bps is expected before the end of the year. Whether we see a subsequent hike in the new year will likely depend on the November and December CPI numbers, but given that CPI is a lagging indicator, there is a real danger of over tightening by the central bank.

Historically, a tightening cycle has foreshadowed an economic downturn, which central banks seem to have made their peace with—a decline in economic growth being the lesser of two evils when faced with entrenched inflation. They will certainly want to avoid a deep recession, however, which was exactly what happened the last time inflation was this high in the early 1980s. It’s somewhat of a Catch-22 for the Fed and the BoC, but they need to aim for enough slack in the economy that if/when they decide to lower interest rates again, inflation won’t come roaring back—this scenario is exactly what happened in North America in the mid-1970s.

Credit Outlook

An economic downturn with higher unemployment and lower corporate profits will in turn lead to widening credit spreads, and we aim to take advantage of such a widening when certain assets become cheap.

Spreads have already widened significantly in 2022, mainly attributable to geopolitical risk coupled with an aggressive hiking cycle and expectations of an economic slowdown. There is no evidence of a slowdown yet in corporates, as Q3 earnings were fairly strong, but estimates for Q4 and next year are coming down and companies such as Walmart, Amazon and Target have sounded the alarm that demand is falling. All eyes will be on consumer spending this festive season.

We have experienced a benign default cycle since the GFC, but that trend isn’t expected to continue and companies with elevated leverage will likely suffer in the next credit cycle. The same can be said for firms that are particularly exposed to inflation or are cyclical in nature. Warren Buffet’s famous quote is apt when considering the credit outlook for 2023: “Only when the tide goes out do you discover who’s been swimming naked.”

In this case, it appears COVID-19 had something of a silver lining in that it forced many companies to go swimsuit shopping. The uncertainty created by a once-in-a-generation (hopefully) pandemic meant many firms strengthened their balance sheets in preparation for any dark days that might lie ahead.

Should the economy contract in early 2023 as is predicted by many economists, businesses with weaker fundamentals may run into trouble, which would mean a new cycle of defaults, mergers and acquisitions (M&As), and leveraged buyouts. Such an environment makes credit selection extra important.

Opportunities undoubtedly come when credit spreads widen, as typically spreads widen indiscriminately across sector and ratings categories, creating relative value opportunities. For example, in the high yield sector, as risk assets are indiscriminately sold, a solid “BB”-rated company may see its spreads distorted, creating attractive valuations. This is the sweet spot in high yield that we often like to invest in. Relative value has been rich as of late, so we have trimmed our higher-beta exposure, but with an eye to adding risk back to our portfolios when central banks start to cut rates.

In our view, credit rating agencies were overly harsh with downgrades during the pandemic. The rapid rebound in the economy coming out of lockdowns has led to a significant number of ”rising stars” (companies upgraded from high yield to investment grade). This is most pronounced in the Energy sector, where companies have kept production growth low and generally done a good job of balancing free cash allocation between bondholders (debt reduction) and shareholders (increased dividends and share buybacks).

On the opposite end of the spectrum are the Retail, Real Estate and Consumer Cyclical sectors, which will likely feel the brunt of the next wave of downgrades if we head into an economic downturn. According to a recent report by Morgan Stanley[1], upgrade volumes in the U.S. this year through October totaled approximately US$444 billion, while downgrades amounted to around US$188 billion. In Canada, there have been no rising stars in the same period (as at October 31), but we have seen two cases of “fallen angels” (bonds that have been downgraded from investment grade to high yield), amounting to C$1.69 billion.

Among the holdings in our fixed income portfolios, Ovintiv, DCP Midstream, Pilgrim’s Pride, and JBS all became rising stars in 2022.

A Defensive Position

Clearly there is a lot for investors to consider heading into 2023. Historically low interest rates and accommodative monetary policy have characterized the post-GFC period. Those days may be behind us, at least for now, so risk assets may need to adjust to an environment of slower growth, above-target inflation and lower earnings.

It’s important to remember that the nature of cycles means change is constant. Periods of growth or decline are a natural part of an economic/credit cycle and bring both opportunities and risks. Heading into 2023, it is likely that the interest-rate hikes of 2022 will put downward pressure on growth in the wider economy. The Fed and the BoC will also be closely monitoring inflation levels with a goal of reaching their target rate (2%) sometime in 2024. Until there are significant steps made towards achieving that goal, we believe a dovish pivot by central banks is unlikely. You might say as likely as Canada’s chances were of winning the World Cup (a long shot).

And to finish off the football analogies, like a rank underdog taking on Brazil, we are adopting a defensive position with our portfolios in this challenging environment. Defensive in this case means upgrading our credit quality, decreasing our credit duration and increasingly liquidity. This will allow us the opportunity to assess the balance sheets of prospective holdings, while waiting for an attractive price, and then adding companies when an opportunity arises. Facing a bleak economic forecast for 2023, we expect further spread widening in the year ahead, but we expect the worst is likely behind us on that front.

In addition to our defensive credit stance and looking ahead to the next rate-cutting cycle, we have increased our exposure to government bonds in the 5- to 10-year part of the curve, as they benefit the most as rates come down; we have also moved our duration bias from neutral to long.

Notes:

[1] “2023 US Credit Strategy Outlook | North America”, Morgan Stanley, 18 November, 2022

Download PDF

Related Topics and Links of Interest:

- Truss Me, I Don’t LDI—Global Lessons from a U.K. Omnishambles

- The Risky Business of a Hiking Cycle

- Curve Confusion

- Beutel Goodman Core Plus Bond Fund

©2022 Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd. Do not sell or modify this document without the prior written consent of Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd. This commentary represents the views of Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd. as at the date indicated.

This document is not intended, and should not be relied upon, to provide legal, financial, accounting, tax, investment or other advice.

Certain portions of this report may contain forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements include statements that are predictive in nature, that depend upon or refer to future events or conditions, or that include words such as “expects”, “anticipates”, “intends”, “plans”, “believes”, “estimates” and other similar forward-looking expressions. In addition, any statement that may be made concerning future performance, strategies or prospects, and possible future action, is also forward-looking statement. Forward-looking statements are based on current expectations and forecasts about future events and are inherently subject to, among other things, risks, uncertainties and assumptions which could cause actual events, results, performance or prospects to be incorrect or to differ materially from those expressed in, or implied by, these forward-looking statements.

These risks, uncertainties and assumptions include, but are not limited to, general economic, political and market factors, domestic and international, interest and foreign exchange rates, equity and capital markets, business competition, technological change, changes in government regulations, unexpected judicial or regulatory proceedings, and catastrophic events. This list of important factors is not exhaustive. Please consider these and other factors carefully before making any investment decisions and avoid placing undue reliance on forward-looking statements Beutel Goodman has no specific intention of updating any forward-looking statements whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise.