By Beutel Goodman’s Fixed Income team

Nostalgia for the 1980s is everywhere nowadays, whether it’s in movies, music or the fashion world. Culturally, the decade is often looked back on favourably, but it’s unlikely you’ll find many people pining for Volcker-era central bank policies in the same way—this was a time when the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) Chair raised the overnight rate to 20% to combat runaway inflation.

It’s a similar problem now—inflation running at its highest levels since the 1980s has become the primary focus of most central banks across the world. The Fed raised its benchmark rate by 75 basis points (bps) in both June and July, while the Bank of Canada (BoC) has been even more hawkish, hiking by a full percentage point in July and 75 bps in September.

Both institutions have committed to doing whatever it takes to bring inflation down, even if it means higher unemployment, slowing down the housing market, or ultimately, causing a recession. These pronouncements are somewhat at odds with current bond market sentiment on the end of the hiking cycle, however.

The U.S. and Canadian bond markets have priced in a front-loaded hiking cycle of more than 350 bps by the end of 2022, followed by rate cuts in 2023. Since the beginning of the year, the BoC has increased its target rate by 300 bps (to 3.25%), while the Fed has hiked 225 bps (target range is currently 2.25–2.50%). At this point, we expect another Fed increase of 50–75 bps at the next Federal Open Market Committee meeting on September 20–21.

Each Cycle Is Unique

Markets have priced in a terminal interest rate of approximately 4.00% in both Canada and the U.S., which would entail additional hikes of 75 bps and 175 bps by the BoC and Fed, respectively, by year end. After this, the market appears to be pricing in an easing cycle, with several different scenarios potentially at play, including:

- A material decline in inflation in the coming months;

- A recession in 2023 that could force central banks to reconsider their hiking cycle; and

- The “Powell Put”— a concept that posits that the Fed is sensitive to deteriorating financial conditions and will pause its tightening cycle if the stock market declines by a significant amount.

It’s our current view that rate cuts are unlikely any time soon, and instead, could potentially reach 4% and above in this cycle.

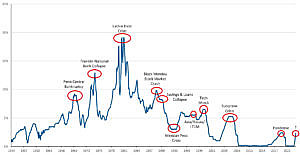

Traditionally in a hiking cycle, a central bank will hike and then pause to see how the economy is doing after absorbing a series of rate increases. They will only start to ease if they break something in the economy. For example, the Tech Wreck of 2000 showcased the unexpected consequences a hiking cycle can bring (see Exhibit 1). We do not believe such a crisis is imminent, although vulnerabilities in the Canadian housing market are a cause for concern. Anything that needs low interest rate money for fuel can be broken when you hike rates, and the housing market is a prime example. In the past, central banks have paused hikes for an average of six to eight months before making their next move.

Exhibit 1: Fed Tightening Cycles and Crises

This line graph shows interest rates during different market shocks that have occurred in the past, from the bankruptcy of Penn Central in 1970 to the COVID-19 pandemic that began in early 2020.

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data, Beutel Goodman, as at August 31, 2022.

Markets love to look at historical precedent because it provides them with a path to follow, and in turn, markets do not like to hear that each time is different, because then there is no roadmap. But each hiking cycle is unique in its own way; the tight job market and low unemployment rate of today is very different from the Volcker era of the 1980s. That period saw unemployment peak in 1982 at 10.8%, before falling to 5.4% by the end of the decade. The high unemployment of the early to middle part of the decade was directly linked to Fed policy that was enacted to combat an inflation rate of 12.5% in 1980. By 1982, inflation had dropped to 3.8%, demonstrating that rate hikes, while painful, usually have the desired effect when it comes to curtailing spiraling prices.

Currently, it appears that markets don’t believe in a pause scenario where central banks bide their time and leave interest rates steady, as this could lead to a period of very limited growth (below 1%) and high inflation that falls slowly, but this path and outcome is a possibility.

Be Wary of a False Dawn

The August Consumer Price Index (CPI) number in the U.S. (prices rose 8.3% year over year and 0.1% over the prior month) served as a painful reminder of how sticky inflation has become. Better-than-expected July CPI data had boosted hopes that we had reached a summit for rising prices, but that respite proved short-lived. Prices do appear to have moderated from the sharp rises of earlier this year, but a two-month period is too small a sample size to make any definitive statements regarding inflation. Looking at core inflation, which excludes food and energy, price changes are reflecting the overall shift in the economy post lockdown, with prices on goods (i.e., cars, clothing and furniture) slowing and prices on services (airfare, leisure, restaurants) increasing. One important thing to note is the impact on inflation from shelter, which measures changes in the cost of housing for renters and homeowners and contributes to a significant amount of core inflation (~40%). Shelter costs have been rising and tend to be sticky as there is a lag for rent resets and changes in house prices. Then there’s the prospect of a wage spiral developing, as workers seek higher pay in response to facing elevated prices for a raft of goods and services. A wage price spiral will make achieving a 2% inflation rate very difficult for central banks.

The inflation that spurred central banks into action in the first half of 2022 was in large part caused by rising energy costs, as well as supply-chain disruptions resulting from the pandemic. This occurred as economies reopened from lockdowns and the supply of goods such as semiconductors could not meet the pent-up demand of consumers, leading to price increases. With the price of oil coming steadily down since peaking in February, wages and housing have now become the primary drivers of inflation in the second half of the year.

Sticking a Soft Landing

Speaking to CNN in July, former U.S. Treasury Secretary Larry Summers had a warning for the wishful thinkers out there: “I think there is a very high likelihood of recession. When we’ve been in this kind of situation before, a recession has essentially always followed. […] Soft landings represent a kind of triumph of hope over experience. I think we’re very unlikely to see one.” BoC Governor Tiff Macklem also said as much in July after the bank’s hike: “The path to this soft landing has narrowed.” On this point, bond markets largely agree, as yield curves have experienced inversions (see our Curve Confusion commentary for a detailed discussion on inverted curves).

Central banks remain focused on taming inflation and will be highly reluctant to ease off on rate hikes that could allow for inflation to reignite, as this would be considered a serious policy error, and very damning to their credibility. Those hoping that the Fed’s Jackson Hole Symposium in August would provide some indication of a possible pivot on rate hikes were left disappointed. In his speech, Fed Chair Powell emphasized the central bank’s main aim of bringing inflation down to its 2% target and that the Fed will likely keep rates restrictive for some time as history cautions against prematurely loosening policy.

The Fed, BoC and their counterparts worldwide clearly have a difficult balancing act to perform, with low inflation and economic growth pulling in opposite directions, but the long-term implications of entrenched inflation mean GDP will likely have to suffer in the short term. With that in mind, our current base case is that bond markets are somewhat prematurely pricing in an easing cycle, and we haven’t moved to a long duration position.

At this juncture, we believe it’s appropriate to proceed with caution and be wary of overly optimistic forecasts for ending the hiking cycle that was a long time in the making. After rates reach 3.0% as expected, we believe that both the Fed and the BoC will likely pause to observe the lay of the land, rather than moving quickly to reduce rates. Every rate cycle is different, but certain developments often seem like déjà vu.

Download PDF

Related Topics and Links of Interest:

- Debt Deals in the Dog Days of Summer

- The End of TINA

- Curve Confusion

- Beutel Goodman Core Plus Bond Fund

©2022 Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd. Do not sell or modify this document without the prior written consent of Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd. This commentary represents the views of Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd. as at the date indicated.

This document is not intended, and should not be relied upon, to provide legal, financial, accounting, tax, investment or other advice.

Certain portions of this report may contain forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements include statements that are predictive in nature, that depend upon or refer to future events or conditions, or that include words such as “expects”, “anticipates”, “intends”, “plans”, “believes”, “estimates” and other similar forward-looking expressions. In addition, any statement that may be made concerning future performance, strategies or prospects, and possible future action, is also forward-looking statement. Forward-looking statements are based on current expectations and forecasts about future events and are inherently subject to, among other things, risks, uncertainties and assumptions which could cause actual events, results, performance or prospects to be incorrect or to differ materially from those expressed in, or implied by, these forward-looking statements.

These risks, uncertainties and assumptions include, but are not limited to, general economic, political and market factors, domestic and international, interest and foreign exchange rates, equity and capital markets, business competition, technological change, changes in government regulations, unexpected judicial or regulatory proceedings, and catastrophic events. This list of important factors is not exhaustive. Please consider these and other factors carefully before making any investment decisions and avoid placing undue reliance on forward-looking statements Beutel Goodman has no specific intention of updating any forward-looking statements whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise.