Summary

A version of this article was first published on the Beutel Goodman website in 2021 and has been updated to reflect growth in the sustainable debt market. Data provided is as at September 30, 2023, unless otherwise indicated.

By Beutel Goodman Fixed Income Team

The bond market plays a unique role in the ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) investment world, as entities can issue bonds to specifically fund an ESG-related project or goal.

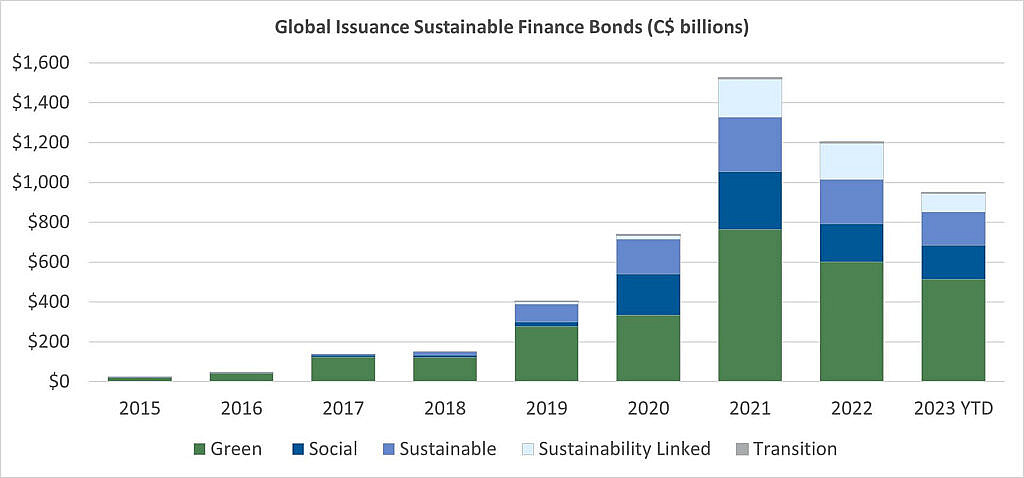

The World Bank issued the first-ever green bond in 2008 and Électricité de France S.A. issued the first green corporate bond in 2013. Since then, the market for sustainable investment has grown exponentially, not only for green bond issuance, but also for social bonds, sustainable bonds, and sustainability-linked bonds and loans, as well as transition and thematic bonds (i.e., blue bonds for water-related initiatives). According to the International Capital Market Association the size of the sustainable debt market is US$3.78 trillion.[1]

Exhibit 1: The Evolution of ESG-Related Financing. This bar graph illustrates the rapid growth of sustainable bonds after 2015, as well as the decline in issuance of these products since 2021.

Sources: Bloomberg L.P., Company reports. YTD 2023 as at September 30, 2023.

The growth of sustainable finance is being fueled by both supply and demand. As companies transition to a lower carbon world and commit to net-zero GHG (greenhouse gas) emissions by 2050, a tremendous amount of investment will be required to facilitate this transition. Investments in renewable power, battery technology, electric vehicles, hydrogen production and transportation, green building, and carbon capture, utilization and storage will all be required, and these investments will need to be financed. According to the World Economic Forum, US$50 trillion of investment will be required by 2050 to transition the global economy to net-zero GHG emissions.[2] As a resource economy, Canada is estimated to need to increase its annual climate investment to between $125 billion and $140 billion from its current levels of $15 billion to $25 billion in order to build a net-zero economy.[3] The U.S. Inflation Reduction Act earmarks US$369 billion to fight climate change and strengthen the domestic industry. [4]

On the demand side, a proliferation of funds with an ESG focus, both passive and active, continues to attract significant inflows. The global universe of sustainable funds totaled US$2,834 billion as at Q2 2023.[5]

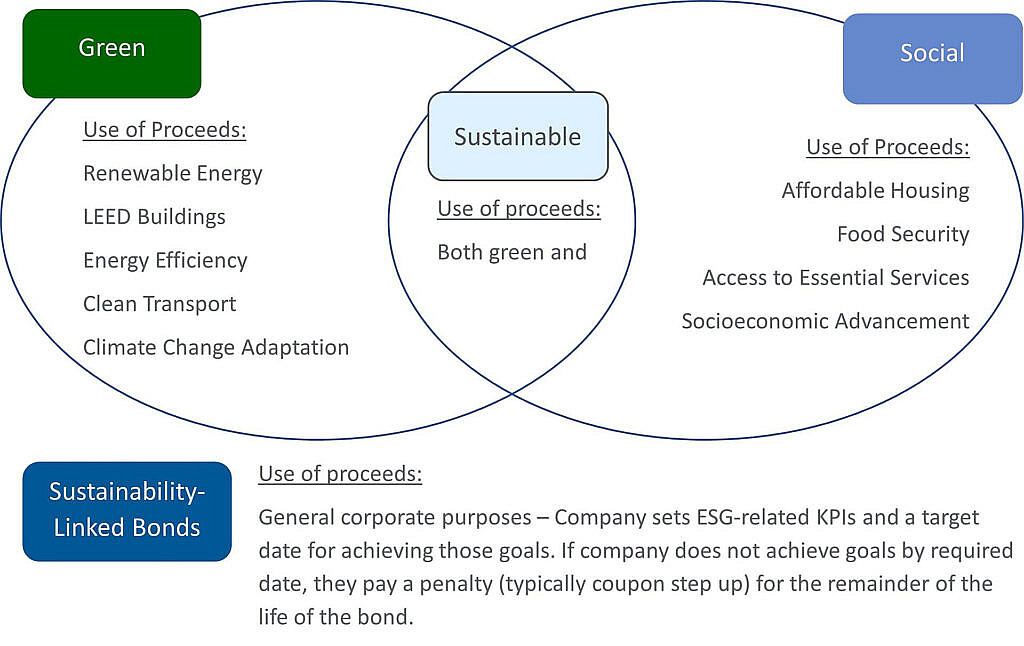

Types of Labelled Bonds

The world of sustainable finance is filled with many colours. Green and social bonds are bonds where the proceeds will be exclusively applied to finance or re-finance green (for green bonds) or social projects (for social bonds) that are typically laid out in the company’s sustainable finance framework. The proceeds from sustainable bonds fund a combination of both green and social projects. Blue bonds are a subset of green bonds whereby eligible projects encompass economic activities that rely on or impact the use of coastal and marine resources. Orange bonds are a new subset of social bonds and use proceeds to fund gender equity globally and in Canada, Indigenous opportunities.

Sustainability-linked bonds (SLBs) are any type of bond instrument for which the financial and/or structural characteristics of the bond can vary depending on whether the issuer achieves predefined sustainability / ESG objectives. Unlike green and social bonds, the proceeds from the issuance are not ring-fenced to green or sustainable purposes and may be used for general corporate purposes. The SLBs are, however, linked to certain key performance indicators (KPIs) to achieve pre-defined sustainability performance targets (SPTs). SLBs are a forward-looking, performance-based instrument through which issuers commit explicitly to future improvements in sustainability outcomes with a pre-defined timeline.[6]

An illustration of sustainable finance is below.

Exhibit 2: The World of Sustainable Finance. This diagram provides examples of the different types of sustainable bonds available to investors, as well as how funds are often used by the issuers.

Source: Beutel Goodman, for illustrative purposes only

Green Bonds

Green bonds were the first sustainable financing product and continue to make up the majority (53.9%) of global sustainable finance issuance. Approximately 43% of green bond proceeds are targeted to renewable energy, as at September 18, 2023.[7]

In Canada, there are $75.4 billion of green bonds outstanding issued by the Government of Canada, the provinces and municipalities, as well as pension plans and corporations.[8] The federal green bond framework was launched in March 2022 and so far, the government has issued one green bond (in March 2022). Under the framework, projects that meet the requirements for eligible green expenditures include clean transportation, natural resource and land use, energy efficiency, terrestrial and aquatic biodiversity, renewable energy, climate change adaptation, sustainable water and wastewater management, circular economy,[9] and pollution prevention and control.[10] It was noteworthy that nuclear was excluded from eligibility, as we believe that nuclear power likely plays a crucial role in the energy transition, and that Canada has a unique opportunity to participate with the development of Small Modular Reactors.

On the corporate side, 35 Canadian companies have issued green bonds, primarily in the real estate, power-generation and financial sectors. The largest issuers have been Brookfield Renewable Power L.P., Brookfield Property Finance ULC, Royal Bank of Canada and Manulife Financial. Eligible projects for real estate green bond frameworks include upgrading to green building certification, energy efficiency improvements, procuring power from renewable energy sources and accommodating electric vehicles (EVs).

In the U.S., green bonds outstanding total US$194.5 billion, issued mostly by corporations.7 Of note, the U.S. Government has yet to issue a green Treasury bond. On the corporate side, 134 companies have issued green bonds, dominated by the utility, real estate, and consumer sectors. The largest issuers are Ardagh Metal Packaging, AES Corporation, Boston Properties Inc. and Verizon Communications Inc. Eligible projects for utility green bond frameworks include transitioning off coal-fired generation, renewable energy projects, modernizing the grid (efficiency) and greening the grid (connecting renewables), new technologies such as battery storage, renewable natural gas and electrification of vehicle fleets.

Biodiversity is emerging as an important area of focus in ESG. In 2022, 60 green bonds were issued with the proceeds used for biodiversity protection projects such as the conservation of flora and fauna, forest protection, protection of endangered species, aquatic and marine protection, and sustainable farming.[11] With the Task-Force on Nature-related Financial Disclosure having recently finalized its recommendations, it is likely that biodiversity-related use of proceeds for green bonds will continue to grow.

Social Bonds

Social bond issuance in Canada has been fairly limited, with only four bonds issued, totaling $1.7 billion. The Government of Canada issued a unique social bond in December 2022, raising $500 million to support the Government of Ukraine to continue to operate in the face of Russia’s invasion. This provided essential services to Ukrainians, such as pensions, the purchase of fuel for the winter, and restoring energy infrastructure. The City of Toronto has issued two social bonds with the proceeds used to fund social objectives such as social and affordable housing, affordable basic infrastructure, access to essential services, and socioeconomic advancement and empowerment.

Social bonds in the U.S. represent a small piece of the sustainable finance universe, with 20 corporate issuers having issued US$14.8 billion. Issuance has been dominated by financial services, with CitiGroup being the largest issuer. The company’s social finance framework helps to provide banking and financing solutions across several business segments, including microfinance, sustainable agribusiness, affordable housing, clean energy, education, health care and sanitation.

Sustainable Bonds

In Canada, there is $16.1 billion of sustainable bonds outstanding from 16 issuers. Government-related issuance is led by the Municipal Finance Authority of British Columbia and OMERS Finance Trust. The top corporate issuers are National Bank of Canada, Bank of Nova Scotia, Sun Life Financial Inc. and Hydro One Ltd. During Q1/2023, Hydro One issued $1.05 billion of bonds under its new sustainable financing framework, becoming the first Canadian utility to issue labelled bonds. The green portion of the framework consists of projects related to greening the distribution and transmission grid, converting the company’s fleet to EVs, energy efficiency and biodiversity conservation. The social aspect of the framework consists of procurement from Indigenous businesses and connecting remote communities to the grid.

In the U.S., there is US$333.8 billion of sustainable bonds outstanding from 16 issuers. On the corporate side, issuance has been dominated by the financial, technology, utility and consumer sectors. The largest issuers are Bank of America Corp., Alphabet Inc., Starwood Property Trust Inc. and Duke Energy Corp. Alphabet’s eligible projects are energy efficiency, clean energy, green buildings, clean transportation, the circular economy, affordable housing, commitment to racial equity, support for small businesses and COVID-19 crisis response.

Sustainability-Linked Loans and Bonds

SLBs are intended to provide sustainability-related incentives by setting KPIs. The financial and/or structural characteristics of SLBs vary depending on whether the company achieves its KPIs. The most common feature is a coupon step up, whereby the coupon of the bond steps up by a fixed amount if a KPI is not met within the predetermined timeframe. Most SLBs have two to three KPIs, with emissions targets the most popular so far, followed by targets related to the circular economy, renewable energy and water. Coupon step downs are rare and the majority of coupon step ups have penalties of 25 bps.[12]

SLB Headwinds

The issuance of SLBs has declined significantly (by 23%) year over year. This is most likely attributable to growing pains within the sector. Poorly constructed SLB frameworks have brought incidents of “greenwashing”[13] to the forefront and led to questions as to the usefulness of the structure in driving improvements in sustainability. Below are some common criticisms of SLB structures and issues we recommend to look out for in SLBs:

- KPIs that are not ambitious enough and too easy for the company to achieve, or are not particularly relevant to the company’s business. Bloomberg News analyzed more than 100 SLBs in 2022 worth almost €70 billion that were sold by global companies to investors in Europe and found that the majority were tied to climate targets that are weak or irrelevant.[14]

- KPIs that do not move the needle towards the company’s SPTs.

- Structures that exclude acquisitions and certain investments made post issuance from the target calculation. KPIs that a company has committed to should be a consideration in its strategic business decisions and apply to its corporate actions.

- Clauses that exempt companies from penalties due to a change in law, regulations, rules, guidelines and policies.

- Structures that allow for targets, base years or calculations to be changed without bondholders’ consent.

- The base year for which KPIs are measured against is often set well before the issue date of the bonds, so it is important to check how the company is already performing against its KPIs and how challenging the remainder is to complete.

- Scope 3 emissions may be problematic as they arise from sources outside of the control of the company, and can be difficult to measure, but should still be addressed and included in the calculation of GHG emissions.

- Penalty payments that are nominal; for example, among the largest SLB issuers, Enbridge Inc.’s penalties would be $45.4 million if the company missed its targets, representing 0.09% of Enbridge’s 2022 net revenues.

- Structures that only have one coupon payment from trigger date to maturity.

- Structures that have a callable date that is prior to the observation date. This would allow a company that is on track to miss its targets to call the bond before triggering a coupon penalty and avoid potential negative consequences from publicly missing its targets.

- GHG emission targets that are based on carbon intensity methodologies. However, a reduction in absolute emissions is what is required to meet net-zero GHG emissions by 2050.

Some examples of what we have considered weak SLB structures include the following:

- A private equity firm in Sweden issued an SLB before even setting any climate targets. Instead, the company’s bond committed it to setting an emissions target that an independent third party would approve. This is an example to us of a weak KPI.

- A French fashion company issued an SLB and by the time the deal had closed, the company had already met its target on Scope 3 emissions reduction. This is an example of having to check progress on KPIs against the base year.

- A U.K. grocery chain issued an SLB with targets tied to reducing its Scope 1 and Scope 2 GHG emissions, which make up only 1.6% of the company’s total carbon footprint (the vast majority of its carbon footprint was Scope 3 emissions). This is an example of KPIs that are not ambitious.

- A European airport authority issued a bond with a KPI aiming to reduce emissions produced by employees travelling to work, ignoring the significant carbon footprint of the airport itself — another example of a KPI that is not ambitious.

There is $11.6 billion of sustainable bonds outstanding in Canada from three corporate issuers — Enbridge Inc., Telus Inc., and Tamarack Valley Energy Ltd. Each of the issues in Canada highlight some of the growing pains in the SLB market. For example, Enbridge has been a prolific issuer within its SLB framework, with five bonds outstanding as of October 31, 2023 totalling $2.4 billion in Canada plus US$3.3 billion in the U.S. The company’s inaugural SLB in June 2021 had three KPIs on GHG intensity reduction, racial and ethnic diversity in the workforce, and female representation on the Board. However, the latest SLB only had the GHG emissions intensity KPI. Further, Enbridge may change the calculation methodology and/or baseline year without the consent of bondholders in the event of a structural change at the company (i.e., merger, divestiture, acquisition), and if there are changes in industry/market standards in methodologies for calculating GHG emissions.

Telus has issued four SLBs totalling $3.25 billion. The structure of the company’s SLBs has, in our view, improved with subsequent issuances. The first SLB that was issued in June 2021 had a maturity of November 13, 2031 and an observation date of December 30, 2030, which we viewed as a very short penalty period for missing the KPI. the latest SLB issued in March 2023, meanwhile, had over two years between the maturity date and observation date.

Tamarack Valley Energy is the only high yield issuer of SLBs in Canada and has issued $500 million of SLBs. A positive factor in Tamarack’s framework is a KPI linked to Indigenous participation in the workforce. However, a weakness in the structure is one common to several high yield SLB issuances; i.e., that there are call dates before the observation date. This leaves it open to the company to call the bonds before triggering the coupon step up if management believes it will miss its targets.

There is US$41.8 billion of sustainable bonds outstanding in the U.S. from 24 corporate issuers, the largest being JBS USA, NRG Energy Inc. and S&P Global Inc. Some of the growing pains in the SLB market are highlighted in these issuances. For example, JBS USA has KPI targets for Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions reduction, but none for Scope 3, which accounts for ~98% of the company’s total GHG emissions. NRG’s KPIs, meanwhile, target Scopes 1, 2 and 3 absolute GHG emissions, which is a strong carbon footprint target. The KPI goal is a 50% reduction by 2025 versus a baseline year of 2014. But by 2019, the data that was available when the first SLB was issued, the company had already achieved a 41.6% reduction in its absolute GHG emissions, leaving a low bar to achieve its KPIs. The weakness in the structure for Solaris Midstream Holding’s SLB is one common to several high yield SLB issuances, in that there are call dates before the observation date. This leaves it open to the company to call the bonds before triggering the coupon step-up if the company believes it will miss its targets.

SLB issuance is not only in the purview of corporates – two sovereigns have issued SLBs. In March 2022, the Republic of Chile issued a US$2 billion, 20-year SLB linked to its sustainability performance targets for reducing absolute greenhouse gas emissions and achieving 50% of its electric power generation from renewable energy sources over the next six years, increasing to 60% by 2032. In March 2022, Uruguay issued a fairly unique SLB. The KPIs were tied to two goals: (1) the country’s nationally determined contributions[15]; and (2) biodiversity (maintenance of the country’s native forest). If the Government of Uruguay does not meet its KPIs, there is the traditional step up in coupon as a penalty; in addition, if the country exceeds its targets, it receives a bonus of a step down in the coupon.

To date, we are only aware of two companies that have missed their KPIs. Polish refiner PKN Orlen’s two SLBs were tied to its MSCI ESG rating. When the company was downgraded in December 2021, it triggered a coupon step up (5 bps for its floating rate note SLB and 10 bps for its fixed coupon SLB). In March 2023, PPC Public Power Corporation, Greece’s largest power utility, announced that it had failed to meet its target to reduce emissions by 40% by year-end 2022, leading to a 50 bps step up in its coupon. The European energy crisis had led to a delay in the company’s off-coal strategy, which caused it to miss its target. It is estimated that approximately one-third of European issuers of SLBs are not on track to meet their targets.[16]

While the issuance of SLBs is in a lull, we do not believe it is the death knell for the product. In addition to stronger structures, there are a few other improvements that could be made to make SLBs more robust. Interim and long-term goals that are verified by the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) will help to increase the credibility of GHG emissions reduction KPIs. Embedding KPIs in bond covenants would also improve the rights of bondholders in case of a missed target, since sustainable bond frameworks are not contractually binding. The penalties for missing a KPI could also be more meaningful; one recommendation is to tie the size of the penalty to the company’s EBITDA instead of to a generic coupon. The industry likely needs to find a balance between making the product more credible while not dissuading issuers from using it. We recommend issuing companies follow the International Capital Market Association (ICMA) guidelines for green, social, sustainable and sustainability-linked bonds.[17]

In June 2023, ICMA published an update to its SLB principles.[18] It recommends that observation dates be intermediate, falling in middle of a lifetime of a bond. First call dates should occur after the observation date, and when that is not possible, the call price should reflect the assumption that the target was not met. In addition, issuers should report key information in a user-friendly format. ICMA also published a database of 300 KPIs, including core KPIs that are material, mature and holistic enough to be standalone, and secondary KPIs that are less material and should be used in conjunction with the core target. For example, in many sectors ICMA views KPIs related to Scope 1,2 3 and emissions as core and KPIs related only to Scope 1 and 2 emissions as secondary. In addition, the Climate Bond Initiative (an international third-party provider of information about sustainable finance) publishes standards and certification designed to ensure that company initiatives are consistent with the goals of the Paris Climate Agreement to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius or lower (based on pre-industrial levels).

Part of the decline in SLB issuance can also be attributed to the dynamic tension in the market around the “greenium”.[19] Issuers believe that due to increased costs in establishing a sustainable framework and monitoring of KPIs, they should receive a discount in the new issue pricing as compared to generic bonds. Many investors believe, however, that the new issue SLBs should be flat to a company’s existing curve, as either the KPIs are not ambitious enough to deserve the greenium, or the KPIs are related to initiatives that the company should be doing regardless of the SLB framework.

Transition Bonds

Transition bonds are use-of-proceeds bonds that fund specific projects that reduce carbon emissions and help issuers with their transitions to net zero, but which do not invest in fully green technology. Transition bonds represent the smallest segment of the sustainable bond market, with US$14.2 billion of debt outstanding. So far, the market has been limited mostly to Asian issuers, specifically Japan, but the market could deepen as more countries like Canada and Australia develop transition taxonomies. There have been no transition bonds issued in Canada nor the U.S. to date.

Transition finance helps address the question “can a ‘brown’ company issue a sustainable bond?” In order to meet the Paris Agreement climate change goals, a significant amount of financing is going to be required from non-green companies to meet GHG reduction targets. Transition bonds provide a potential solution by enabling carbon-intensive companies to raise capital and use the proceeds for activities that help them to reduce their carbon footprint. Transition bonds are typically issued in sectors that are traditionally difficult to decarbonize, such as steel, chemicals and aviation.

ICMA issued its Climate Transition Handbook[20] in June 2023 with the following recommendations for transition finance:

- Issuers have a climate transition strategy and governance.

- The climate transition strategy should be relevant to the environmentally material parts of an issuer’s business model and consider potential future scenarios.

- An issuer’s climate transition strategy should reference science-based targets and transition pathways.

- Market communication on the use of proceeds should be transparent, and to the extent practicable, include capital and operational expenditures.

An example of a transition bond is Japan Airlines Co. Ltd.’s (JAL) five-year bond issued in March 2022. Instead of a taxonomy, Japan has published technology roadmaps for nine hard-to-abate sectors and requires transition bonds to be backed by company level transition plans. The use of proceeds for the JAL financing are to upgrade the company’s aircraft to become more fuel-efficient. JAL plans to have sustainable aviation fuel make up 10% of its total fuel requirements by 2030. The company has committed to net-zero GHG emissions by 2050 with short- and medium-term GHG reduction goals.

Canadian Taxonomy

On March 3, 2023, the Sustainable Finance Action Council (SFAC) released the Taxonomy Roadmap Report. The Taxonomy report’s objective is to foster the issuance of green and transition financial instruments that are consistent with Canada’s goal of achieving net-zero emissions by 2050, and with the Paris-aligned commitment to keep the global temperature rise to below 1.5° C (based on pre-industrial levels). Eligible transition projects include those that decarbonize sectors that historically have (1) high Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions (iron and steel, chemicals, aluminum and cement production); and (2) high downstream Scope 3 emissions (oil and gas, or gas-fueled vehicles). These projects must have well-defined lifespans that are approximately proportionate to the expected decline in global demand in representative 1.5° C pathways. Examples include installing methane capture on existing natural gas production or developing carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS). All projects related to solid fossil fuels (thermal coal mining, coal-fired power generation), that are at a high risk of becoming stranded in net-zero pathways, have Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions that are inconsistent with net-zero pathways, and/or those that are unable to scale in transition (exploration and development of new oil fields) will be ineligible. In order to issue transition bonds using the taxonomy, companies must have net-zero targets and a climate transition plan.[21] The Taxonomy Roadmap has not yet been endorsed by the Canadian government.

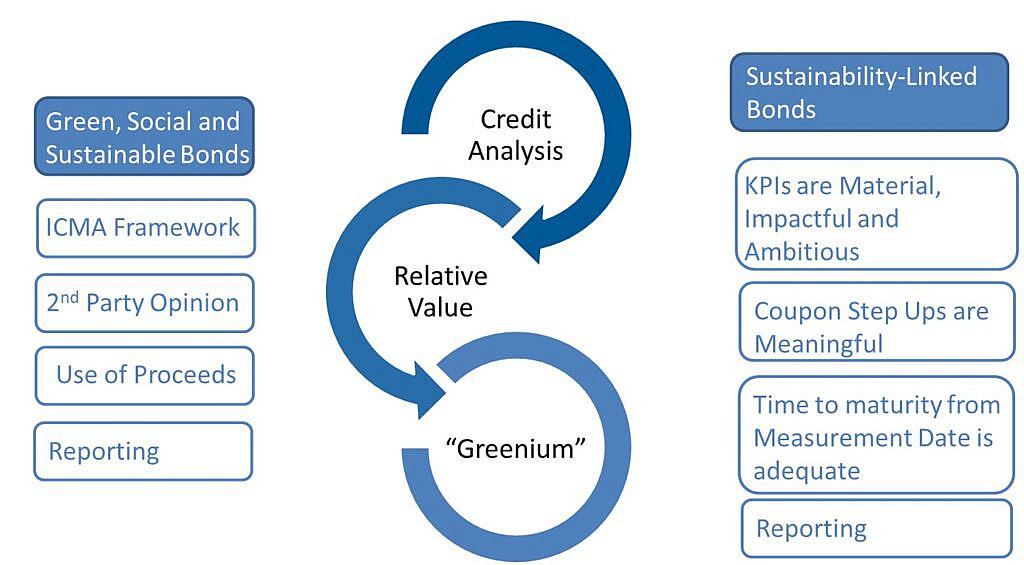

Sustainable Investing at Beutel Goodman

Beutel Goodman has purchased green, social and sustainability-linked bonds across all of our fixed income portfolios and is ready to evaluate transition bonds, when and if they are issued. As value — not “values” — investors, we do not buy any issue simply because it is labelled as part of the sustainable finance spectrum. We follow a rigorous process for the evaluation of securities in all of our fixed income strategies and portfolios. First, extensive due diligence on the issuer itself is completed and the issuer must be on our Approved List. Second, any labelled bond (green, social, or sustainable or sustainability-linked) must meet at the minimum the following criteria:

- Be issued under an ICMA framework;

- Have a second-party opinion on the bond framework and use of proceeds;[22]

- The use of proceeds are clearly defined; and

- The projects funded are verified, updated annually and audited.

Sustainability-linked bonds are further evaluated under the following criteria:

- Ambitious targets that are challenging for the company to achieve and material to the company’s business.

- Environmental KPIs that align with a pathway to net-zero GHG emissions by 2050.

- A sufficient length of time between observation date and maturity date.

- Frameworks that hold the issuer accountable.

- A meaningful penalty for missed KPIs.

- KPIs that are measurable, published annually and verified.

Exhibit 3: Beutel Goodman’s Sustainable Finance Evaluation Process. This illustration shows the criteria Beutel Goodman applies before selecting a sustainable bond for one of our fixed income portfolios.

Source: Beutel Goodman, for illustrative purposes only, and may not represent all considerations in our process.

Lastly, the relative value proposition has to be attractive and the company must have earned any greenium with the strength of its sustainable finance structure. Generally speaking, we do not favour greeniums, especially for SLBs.

We may buy a labelled bond for our portfolio if the relative value is attractive, but if the sustainable finance structure does not meet our criteria, then we would not count that bond as “sustainable finance” in our sustainable bond fund strategies.[23]

We also believe that there are some labelled bonds that do not need a label. We define these as quasi green or social bonds. In some cases, the company’s business is limited to activities that align with a green use of proceeds. For example, Lower Mattagami Limited Partnership’s business is limited to the refurbishment of four hydroelectric dams in Northern Ontario. While the partnership has issued both green and non-green bonds, we consider all of their outstanding bonds as green in our sustainable bond portfolio weights. Another example is First Nations Financing Authority (FNFA). FNFA is a not-for-profit, non-share capital corporation with a mandate to provide cost-effective financing, capital planning and investment management services to First Nations communities in Canada. The issuer is also backed by a legislative framework and in our opinion qualifies as a quasi-social bond.

To conclude, the sustainable bond market has come a long way since the first green bonds emerged in 2008. This segment of fixed income continues to grow and alongside that growth comes a need for a disciplined evaluation of labelled bonds. Corporate transparency is key in investing and is essential for ESG to maintain its momentum and become an ever-present factor in effective asset management. In that respect, we welcome any changes that allow investors greater clarity into the sometimes-complex world of sustainable bonds.

[1] https://www.icmagroup.org/sustainable-finance/sustainable-bonds-database/. As of October 31, 2023.

[2] “Financing the Transition to Net-Zero Future”, The World Economic Forum, October 2021.

[3] “Taxonomy Roadmap Report”, Sustainable Finance Action Council, September 2022.

[4] https://www.forbes.com/sites/energyinnovation/2022/08/02/the-inflation-reduction-act-is-the-most-important-climate-action-in-us-history/?sh=5fcd25d434db.

[5] “Global Sustainable Fund Flows: Q2 2023 In Review”, Morningstar, July 26, 2023. Morningstar defines sustainable funds as funds that use ESG criteria to evaluate investments or assess their societal impact.

[6] International Capital Market Association Sustainable Finance Guidelines and Handbooks, https://www.icmagroup.org/sustainable-finance/the-principles-guidelines-and-handbooks.

[7] Luan, Jonathan, “Green Bonds Fail to Target Most Carbon Efficient Sectors”, Bloomberg News, September 18, 2023.

[8] All references to sustainable finance data outstanding are compiled from Bloomberg L.P. Unless otherwise indicated, the data is as at September 30, 2023.

[9] The circular economy is a model of production and consumption, which involves sharing, leasing, reusing, repairing, refurbishing and recycling existing materials and products as long as possible. In this way, the life cycle of products is extended.

[10] “Government of Canada Green Bond Framework”, March 2022 https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/programs/financial-sector-policy/securities/debt-program/canadas-green-bond-framework.html.

[11] “Sustainable Debt Global State of the Market” Climate Bond Initiative, April 2023.

[12] Based on a study by Barclays Credit Research of 164 index-eligible SLBs: “Charting the SLB Market”, Barclays Credit Research, May 5, 2023.

[13] Greenwashing is the act or practice of making a product, policy, activity, etc. appear to be more environmentally friendly or less environmentally damaging than it really is (Merriam-Webster Dictionary).

[14] Azevedo Rocha, Priscila; Rathi, Akshat; Gillespie, Todd, “Greenwashing Enters a $22 Trillion Debt Market, Derailing Climate Goals”, Bloomberg News, October 4, 2022.

[15] Nationally determined contributions (NDCs) embody efforts by each country to reduce national emissions and adapt to the impacts of climate change. The Paris Agreement requests each country to outline and communicate their post-2020 climate actions, known as their NDCs.

[16] “The Green Bond Report”, SEB Securities Inc. September 7, 2023. https://sebgroup.com/our-offering/prospectuses-and-downloads/research-reports/green-bond-report.

[17] The Principles, Guidelines and Handbooks, International Capital Market Association, https://www.icmagroup.org/sustainable-finance/the-principles-guidelines-and-handbooks.

[18] International Capital Market Sustainability-linked Bond Principles, https://www.icmagroup.org/assets/documents/Sustainable-finance/2023-updates/Sustainability-Linked-Bond-Principles-June-2023-220623.pdf.

[19] “Greenium,” or green premium, is the amount by which the yield on a green bond is lower than an otherwise identical conventional bond.

[20] Climate Transition Finance Handbook, International Capital Market Association, https://www.icmagroup.org/sustainable-finance/the-principles-guidelines-and-handbooks/climate-transition-finance-handbook.

[21] “Taxonomy Roadmap Report”, The Government of Canada, https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/programs/financial-sector-policy/sustainable-finance/sustainable-finance-action-council/taxonomy-roadmap-report.html.

[22] A Second Party Opinion normally entails an assessment of the alignment of the issuer’s Green, Social Sustainability Bond and SLB issuance/framework/program with the ICMA Principles. An institution with environmental/ social/sustainability expertise that is independent from the issuer may provide a Second Party Opinion.

[23] The BG Sustainable Bond Fund, a private fund available to discretionary managed account clients only, and the BG U.S. Sustainable Bond Strategy, have a permitted range of 20%–80% for labelled (green, social, sustainable and sustainability-linked) bonds.

Download PDF

Related Topics and Links of Interest:

- Trouble with the Curve

- Hard or Soft ― How Do You Like Your Landing?

- Holding the “a-pause” for Central Bank Policy

©2023 Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd. Do not sell or modify this document without the prior written consent of Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd. This commentary represents the views of Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd. as at the date indicated.

This document does not constitute an offer or a solicitation to buy or to sell any security, product or service in any jurisdiction. This document is not available for distribution to people in jurisdictions where such distribution would be prohibited.

This document is not intended, and should not be relied upon, to provide legal, financial, accounting, tax, investment or other advice. Beutel Goodman has taken reasonable steps to provide accurate and reliable information. Beutel Goodman reserves the right, at any time and without notice, to amend or cease publication of the information.

Please note Beutel Goodman’s ESG and responsible investing approach may evolve over time. We do not use ESG factors to pursue non-financial ESG performance. Also note that the integration of ESG and responsible investing considerations into our investment process does not guarantee positive returns. Past performance does not guarantee future results.

For more information on our approach to ESG and Responsible Investing, please visit https://www.beutelgoodman.com/about-us/responsible-investing/.

Certain portions of this report may contain forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements include statements that are predictive in nature, that depend upon or refer to future events or conditions, or that include words such as “expects”, “anticipates”, “intends”, “plans”, “believes”, “estimates” and other similar forward-looking expressions. In addition, any statement that may be made concerning future performance, strategies or prospects, and possible future action, is also forward-looking statement. Forward-looking statements are based on current expectations and forecasts about future events and are inherently subject to, among other things, risks, uncertainties and assumptions which could cause actual events, results, performance or prospects to be incorrect or to differ materially from those expressed in, or implied by, these forward-looking statements.

These risks, uncertainties and assumptions include, but are not limited to, general economic, political and market factors, domestic and international, interest and foreign exchange rates, equity and capital markets, business competition, technological change, changes in government regulations, unexpected judicial or regulatory proceedings, and catastrophic events. This list of important factors is not exhaustive. Please consider these and other factors carefully before making any investment decisions and avoid placing undue reliance on forward-looking statements Beutel Goodman has no specific intention of updating any forward-looking statements whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise