– By Beutel Goodman’s Fixed Income team

If one was to form all their opinions based on the doom-filled spattering of daily headlines, they may find themselves trapped by pessimism. A skeptical person might simply call that negative news the core of the media business model. A psychologist might tell you that the reaction is the definition of negativity bias in action. And a bearish investor might suggest it all means that the market is headed for major reversal of fortunes. But the curious person will always ask what the deeper story is.

On the surface, things may indeed seem quite negative. We’ve barely turned the calendar on 2022, but we’ve already seen higher volatility in major equity indices, wider credit spreads, persistent inflation, increasingly hawkish monetary policy, the ongoing pandemic, and a slowdown in economic growth. None of that sounds great for investors, but like headache-inducing headlines, crucial context and nuance is omitted. One of, if not the most, important pieces of the puzzle is missing – the consumer.

Today, the developed world, and by extension the global economy, is largely driven by the consumer. There is no doubt that many people have been seriously affected by COVID-19 and the response to it, which triggered the sharp but brief recession of 2020. But what isn’t entirely clear in the popular media is how consumers have managed on aggregate. Humans are adaptive and resilient. It’s one of the reasons why we’ve been so successful as a species in a relatively short time, as far as natural history is concerned. It’s also why we don’t believe the world is on the brink of an economic dark age.

Headline Headaches and Common-Sense Remedies

The recent volatility in equity markets is perhaps the most striking bad-news headline of late. In January, the S&P 500 Index declined 9.2% peak-to-trough (January 3 – January 27), although it reclaimed some losses in the final days of the month to end down nearly 5.2%. Losses were even more pronounced on the Nasdaq, which slumped 9.0% over the month, narrowly missing the title of its worst January ever. These are not very optimistic numbers, but if we zoom out, we can see these indices are still roughly double the level they set during the lows of March 2020, the depth of the COVID recession.

Similar movements were seen in the credit markets as well, as spreads widened through January. U.S. investment grade and high yield credit spreads widened by approximately 12 and 60 basis points, respectively. For high yield, spreads hit their widest levels since the Omicron-induced scare in November 2021. Canadian investment grade spreads widened by approximately 11 basis points, as the commodity-heavy Canadian market fared better than its southern neighbour (the same is true on the equity side, as the S&P/TSX Composite Index clawed back nearly all of its mid-month losses). Monetary policy tightening is all but inevitable at this point. The U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) doubled the pace of its planned tapering of its bond-buying stimulus program, which is now set to end in early Spring 2022. The Fed is projecting three interest rate hikes this year, although we believe one or two more may be more likely. Investors are now speculating about balance sheet reductions by the U.S. central bank. And it’s not just an American phenomenon, as most of the major global central banks have at least alluded to some form of tightening in the near future.

At face value, it might seem that ending the easy-money policies of the past decade may be akin to central banks pulling the rug out from under investors. But we’d ask what, if anything at all, is negative about central banks feeling confident enough to hand off the economy from stimulus programs back to its main driver, the consumer? If the economy cannot sustain itself without constant intervention, it’s not much of an economy to begin with. The evidence right now suggests the economy can indeed handle it, and given the stickiness of inflation, needs an environment of monetary tightening.

Persistently high demand-driven inflation feeds on itself, with higher prices leading to higher wages and back into higher prices. Ultimately, if inflation continues unabated, the purchasing power of the consumer is destroyed, as is the wealth of savers. Inflation also reduces real growth, as it effectively acts as a tax on consumption – especially on items like gasoline, which are consistent inputs in many lives and cannot be avoided. We believe inflation will moderate towards 3% in 2022, but it is proving less transitory than most central banks originally expected. The central banks have finally acknowledged this, which is why they will raise interest rates to seek price stability and long-term growth.

Lastly, annual economic growth is slowing. However, like with capital markets, taking a longer-term view helps contextualize the deceleration. The 5.7% growth in GDP in 2021 was the biggest print in nearly four decades for the U.S. That strong number came on the heels of the 3.4% decline in 2020. In other words, part of 2021’s success was due to the base effect of 2020’s weakness. A slowdown in 2022 is highly likely (and predicted by virtually all economists, including those at the Fed), and perhaps coming a bit quicker thanks to the rise in inflation and tighter monetary policy. That said, we still believe the U.S. economy will perform above its more recent historical levels of about 2% this year, thanks largely to the consumer.

Put Some Confidence in the Consumer

While the items discussed above may appear worse than they are, we believe the inverse is true when it comes to the consumer. The consumer is in fairly good shape; stronger than what might be apparent from the prevailing narratives in popular media. And the consumer may end up being the economic MVP at this point in the cycle, especially when compared to the last period of significant distress – the global financial crisis (GFC).

Consumers require money to consume, and most people draw that in the form of income from a job. The job market in the U.S. is strong, with the unemployment rate down to 3.9% in December 2021, the lowest level since February 2020 (although it is still slightly above pre-COVID levels amid a severe labour shortage). As of the end of January 2022, government reports show there were roughly 6.5 million unemployed Americans and as of the end of December 2021, nearly 11 million job openings. While there are likely many factors at play, on its face, there are about 1.7 jobs available for every jobseeker. There is also room for existing workers to climb the professional ladder (and earn more income) by moving to higher-level jobs at other companies. This is in stark contrast to the GFC, which saw unemployment peak at 10%; it took more than five years for the jobless rate to get back below 5% despite a steady rise in the number of job openings. A similar trend is visible in Canada as well, although it is not nearly as pronounced. The unemployment rate continues to decline, with roughly 1.3 million unemployed Canadians in January and an all-time high of 912,600 job openings at the end of the third quarter of 2021 (Statistics Canada only provides quarterly reports on job openings).

Along with an improving employment situation, many consumers have been strengthening their own balance sheets. The personal savings rate in the U.S. spiked to nearly 34% at the beginning of the pandemic and remained elevated for well over a year, only returning to more historical norms around 7% recently. Again, this is in great contrast to what we saw in the GFC period, where the savings rate only briefly spiked above 10% more than four years after the onset of the crisis. Part of the sharp rise in savings can be explained by government stimulus cheques and fewer places to spend the money due to COVID lockdowns, something that didn’t happen during the GFC. In Canada, where stimulus money was not sent to virtually all citizens, the savings rate spiked more modestly to 28%, but remains well above historical norms at 11% at the end of the third quarter of 2021 (again, this is only reported on a quarterly basis). This increase in savings is further heightened by the rise in asset prices, including real estate and securities, which together fuel a wealth effect that is particularly notable for middle- and high-income earners. It’s yet another contrast from the GFC, which led to broad declines in property and investment values.

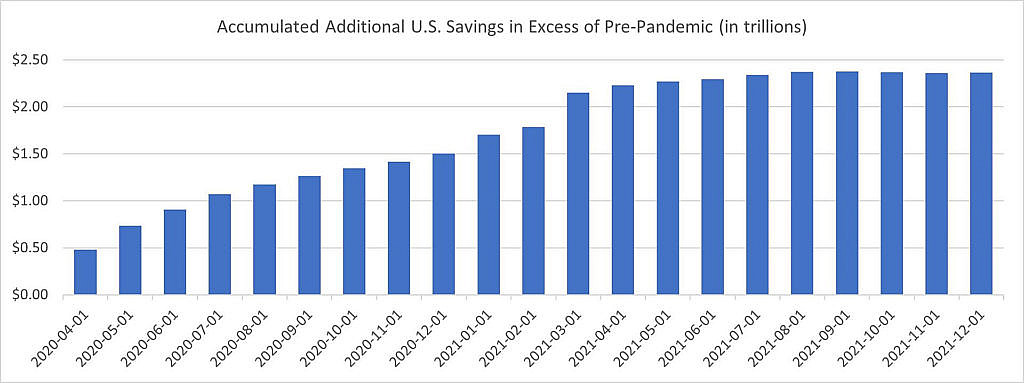

Figure 1 shows the amount of new savings above the trendline by U.S. consumers during the pandemic era. More than $2 trillion in new savings has been accumulated, however the rate of savings has returned to pre-pandemic levels more recently.

Source: BEA, Bloomberg Economics

Of the items discussed, the one with the biggest potential to derail the power of the consumer is inflation. However, the story isn’t all bad on that front. Yes, it will force some consumers to change their spending habits. Certain costs, like gasoline, will take up a bigger portion of spending for some people. However, it seems unlikely that inflation will significantly reduce spending overall, particularly as inflation issues unwind over time. Part of the reason for this is the fact that inflation is also occurring in the one place where it’s widely welcomed: wages. Wages are seeing consistent upward pressure across nearly all industries, something that hasn’t happened since the early 2000s. While both the GFC and 2020 recession sparked a decline in wages at the onset, during the GFC that wage loss lasted for more than two years before slowly normalizing. This time, the decline was brief and followed by a surge in wage growth, which has remained well above historical levels since April 2021 in the U.S. and normalized recently in Canada after a year of above-average gains.

Lastly, we should note that consumers are largely confident about their prospects. Consumer confidence surveys in both the U.S. and Canada show levels just below where they were pre-pandemic. While the pandemic and recession of 2020 put people on their heels, they did not become outright pessimistic for an extended period, as they did in the aftermath of the GFC.

People Power Prevails

We have presented you with two lists – one of pessimistic economic headlines and one of reasons for optimism, given the health of the consumer. While it’s easy to get caught up in all-or-nothing rhetoric, as thoughtful investors it is our duty and challenge to sift through the news and the noise to make sound investment decisions. While we believe some degree of caution is warranted because financial conditions are tightening, prices are elevated, and the economy is slowing, we are not giving in to the pessimism of the headlines of early 2022.

The consumer typically provides about two-thirds of the growth seen in the U.S. economy. Spending can be lumpy, so we are not setting this prediction in stone, but we believe the consumer could generate upwards of 75% of this year’s economic growth. And that is a direct reflection of the handoff of the economy from monetary stimulus to the consumer.

While inflation will take a toll on growth, the consumer is now more well-equipped than in previous cycles to manage price increases. The combination of the recession and the COVID lockdowns made saving a viable option, particularly among higher-earning professionals who worked from home and were not laid off as they may have been in other recessions.

Inflation can hurt and growth can shift into a lower gear, but if it wasn’t for the strength of the consumer, we may not have seen such a strong rebound in the first place. The recovery could have been much slower, as it was after the GFC. It’s smart to be cautious at times like these, but we think it’s foolhardy to underestimate the power of the consumer.

Download PDF

Related Topics and Links of Interest:

- Keep Calm and “Carry” On – 2022 Credit Outlook

- China’s Slowdown: An Aging Dragon Can Still Breathe Fire

- (Don’t Fear) The Taper

©2022 Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd. Do not sell or modify this document without the prior written consent of Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd. This commentary represents the views of Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd. as at the date indicated.

This document is not intended, and should not be relied upon, to provide legal, financial, accounting, tax, investment or other advice.

Certain portions of this report may contain forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements include statements that are predictive in nature, that depend upon or refer to future events or conditions, or that include words such as “expects”, “anticipates”, “intends”, “plans”, “believes”, “estimates” and other similar forward-looking expressions. In addition, any statement that may be made concerning future performance, strategies or prospects, and possible future action, is also forward-looking statement. Forward-looking statements are based on current expectations and forecasts about future events and are inherently subject to, among other things, risks, uncertainties and assumptions which could cause actual events, results, performance or prospects to be incorrect or to differ materially from those expressed in, or implied by, these forward-looking statements.

These risks, uncertainties and assumptions include, but are not limited to, general economic, political and market factors, domestic and international, interest and foreign exchange rates, equity and capital markets, business competition, technological change, changes in government regulations, unexpected judicial or regulatory proceedings, and catastrophic events. This list of important factors is not exhaustive. Please consider these and other factors carefully before making any investment decisions and avoid placing undue reliance on forward-looking statements Beutel Goodman has no specific intention of updating any forward-looking statements whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise.