By Beutel Goodman’s Fixed Income team

In discussing securities markets, conversations can sometimes be high on jargon and low on relatability for the average person. Inflation is something that affects everyone, though — having much less money in our collective pockets is a major concern for investors, consumers, and business owners alike.

For that reason, a focus in 2022 has been on the monthly inflation releases from Statistics Canada and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, as well as on inflation expectations that are released in various confidence surveys. For the most part, these reports show that inflation pressures weighed negatively on consumers and businesses throughout the year.

That has started to change over the past three months, however, with some positive developments in year-over-year inflation data in both the U.S. and Canada. A slowdown in the pace of price increases has also led to a decrease in bond yields. It appears that as inflation progresses on a path to central bank targets, fixed income investors expect inflation-fighting central banks to ease off on the aggressive rate-hiking cycle and possibly even consider cutting interest rates later in 2023, depending on the severity of any economic slowdown.

Beware the False Narrative

It appears that a slowdown of headline inflation increases in the second half of 2022 has allowed a disinflation narrative to take hold, and this is having an impact on bond markets. However, in our view, expectations for rate cuts anytime soon are overly optimistic, as it is likely too early for central banks to declare victory in the battle against persistently high inflation. All Items CPI (year over year) in Canada peaked at 8.1% in June 2022 before declining to 6.3% in December. Similarly, All-Items CPI in the U.S. declined to 6.5% in December 2022 from a peak of 9.1% in June. As we journey back down towards the Bank of Canada’s (BoC) and U.S. Federal Reserve’s (Fed) inflation targets of 2%, we believe that there will be some easy wins before a bit of a tougher slog.

One of those easy wins is the continued easing of commodity prices, which surged following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022. By March, for example, the price of West Texas Intermediate crude oil had breached US$120/barrel, but prices have since fallen to below US$80/barrel. This decline is also being reflected at the pumps, where gasoline fell by 13.1% between November and December 2022 – the largest monthly decline since April 2020. We expect these negative “base effects” to continue into the summer as headline CPI declines on an annual basis toward 3-4%. However, we believe it is unlikely that all components of inflation will fall as quickly.

Flexible and Sticky Prices

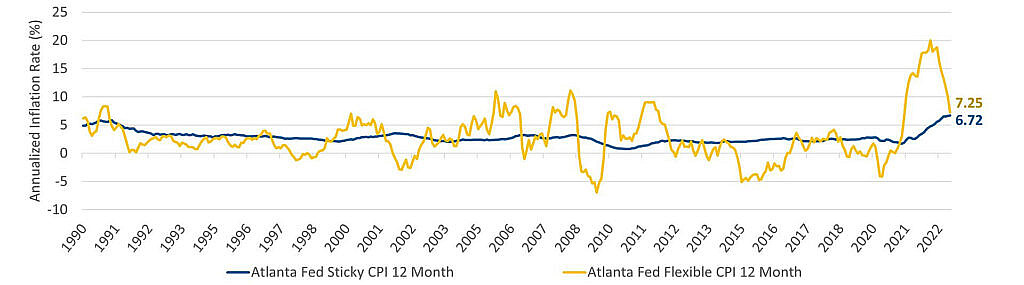

Inflation is a measure of pricing levels of a basket of goods. The pricing of some of these goods tend to be variable – or “flexible” – in nature, while others tend to be more stable – or “sticky”. Exhibit 1 below shows the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s Flexible Price and Sticky Price Consumer Price Indices and the extreme impact the pandemic had on flexible-priced good and services between 2020 and 2022. The pace of flexible price increases has now slowed; however, the same downward trajectory is yet to be seen with the Sticky Price CPI.

Gas is a prime example of a product with flexible pricing that experienced heightened volatility in 2022, due in large part to the war in Ukraine. The flexible-priced components of CPI, which also includes cars and other goods that faced supply-chain constraints, have been key contributors to the year-over-year inflation rate falling in recent months. According to the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, the flexible price measure is more responsive to changes in the current economic environment or the level of economic slack[1]. However, flexible-price components on average represent only 30%-35% of CPI.

On the other hand, the Sticky Price CPI incorporates expectations about future inflation1. Given that sticky prices make up the bulk of CPI and are most directly tied to wages and a strong labour market, it is with the sticky-priced components – which includes most services – that the Fed and the BoC face their greatest challenge.

Exhibit 1: CPI: Sticky vs Flexible Prices. This line graph shows the Federal Reserve of Atlanta breakdown of the 12-month Flexible Price Consumer Price Index and Sticky Price Consumer Index over the last 35 years. The period from 2021 to 2022 shows the extreme inflation associated with the pandemic and how flexible-priced goods peaked midway through 2022. Twelve-month sticky-priced goods, however, appeared to still be on the rise as at January 31, 2023.

Source: Beutel Goodman, Macrobond, Bloomberg L.P., as at January 31, 2023

Contrasts in Food and Housing

Food is also a large part of the Flexible Index, and like oil, saw a surge in prices in 2022 due to volatility in commodities such as grain and fertilizer resulting from the conflict in Ukraine. Higher wage costs for the production of food have also contributed to inflation in this segment, as have force majeure events such as drought in California limiting the supply of fresh produce, and the avian flu outbreak in North America that required the culling of chicken and eggs.

War, drought and disease: the past year has been biblically difficult for food producers and this pain has been passed on to consumers in the form of higher grocery bills. In Canada, the year-over-year CPI reading for December for food purchased from stores was 11% (although down from 11.4% in November), while in the U.S., the Food Index increased 10.4% year over year (down from 10.6% in November).

It is important to note that the prices that customers pay at the checkout lag any reduction in the costs of production. Prices for food commodities have been steadily declining since last summer, as has the cost of shipping as supply-chain bottlenecks have eased. However, we have yet to see these lower costs be passed through to consumers. It is likely that food prices in stores will stabilize in the coming months, albeit at a higher level, unless some more unforeseen misfortune impacts global production.

A Chill in Canada’s Molten-Hot Housing Market

While the Fed and the BoC have little influence over war in Eastern Europe or extreme weather in California, their policies can have a major bearing on the housing segment. In Canada, house prices have tracked consistently downward since the central bank began its tightening cycle, confirming the inverse relationship between interest rates and house prices. Canadian house prices are currently down approximately 10% from their peak in May 2022, according to Teranet’s December 2022 Residential Price Index.

It is important to note that the transmission mechanism of home prices into the consumer price indices operates with a significant lag, and we have yet to see the full decline in the market prices reflected in CPI. In Canada, shelter CPI is comprised of three major components: rent, mortgage interest costs and homeowners’ replacement cost (a proxy for house prices). Given the increase in rates, the mortgage interest component of CPI is up 18% year over year in December, following a 14.5% increase in November. The homeowners’ replacement cost was also up, although by a lesser 4.7% year over year; this is down from a September 2022 peak year-over-year change of 14.4%. Rent also remains elevated, at 5.8% year over year in December.

In the U.S., the Shelter Index, which includes rent and owners’ equivalent rent (a proxy for the cost of owned housing), increased by 7.5% year over year in December (November’s reading was 7.1%) and remains a significant contributor to core inflation.

Moving forward, we expect that the pass-through of house prices will move shelter inflation lower in Canada and the U.S., but likely by less than many think. This is due to the fact that rents will likely increase as many potential homebuyers can no longer qualify for mortgages or prefer to rent while waiting for housing to stabilize. In addition, both Canada and the U.S have significantly increased their immigration target for 2023 and beyond, which also generally pushes rents higher.

Hitting the Pause Button on Rates

Following the December CPI announcement, U.S. President Joe Biden addressed the fight against inflation, saying: “We’re clearly moving in the right direction … [i]t all adds up to a real break for consumers, more breathing room for families.” Headline inflation coming down is no doubt positive, but core inflation will need to follow suit before the Fed and BoC know their hawkish shift is having the desired effect.

In their early 2023 rate announcements, both central banks raised their key rates for the eighth consecutive time (to 4.5% in Canada and 4.50%–4.75% in the U.S.). This aggressive hiking cycle has yet to be felt in the economy to a significant degree, as the labour market was tight when the hiking cycles began. The consensus among economists is that a recession is likely some time in 2023.

As a result, the Fed and the BoC have both lowered their inflation forecasts, and while the BoC has paused its hiking cycle, the Fed likely has a couple more hikes left.

Now Comes the Hard Part

The BoC has forecast CPI inflation to fall to approximately 3% by the middle of this year and to 2.6% by the fourth quarter. The central bank believes this trend means inflation should return to its 2% target in 2024. The Fed, meanwhile, forecasts that inflation (the Fed uses Core PCE as its benchmark measure) will decline to 3.1% in 2023 and 2.5% in 2024 before returning to its ~2% target in 2025.

Given the trends we have already observed, it is currently our base case that inflation will continue to abate in 2023, but this is where our forecast diverges from that of central banks. We do not believe inflation is likely to decline all the way back down to targets during 2023, as in our view, sticky inflation will become harder to reduce. The decline from 8% to 4% should be the easy part of disinflation, as supply-side inflation pressures abate. It is the next leg down in inflation that is more difficult and will require demand destruction – or “significant slack”, as central bankers call it – to be created in the economy. This “slack” they refer to will likely come in the form of a higher unemployment rate.

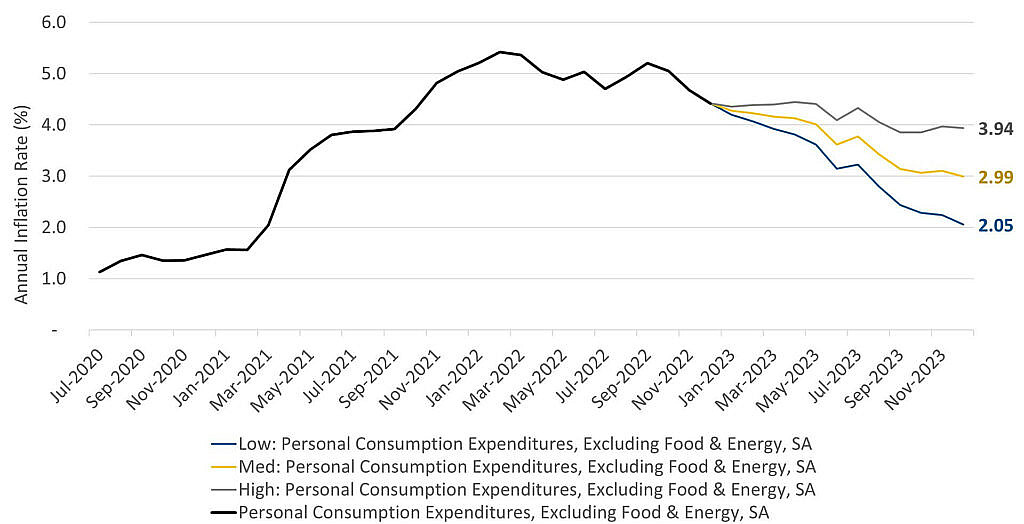

Focusing on the U.S., Exhibits 2 and 3 show some of the different scenarios for core inflation this year.

Exhibit 2: Inflation Scenarios. Given the base-effect in measuring year-over-year core inflation, it is likely we will see a slowdown in price growth in the U.S. in the coming months. The line graph shows three scenarios for U.S. PCE inflation in 2023. In the low-inflation scenario, the rate falls to 2.05% by December 2023, while the medium- and high-inflation scenarios point to rates of 2.99% and 3.94%, respectively, by the end of the year.

Source: Beutel Goodman, Macrobond, Bloomberg L.P., as at January 31, 2023.

Exhibit 3: U.S. Core Prices Scenario Table. The “low”, “medium” and “high” estimates for inflation in Exhibit 2 are based on the estimates in Exhibit 3 below. The month-over-month estimates are based on combining Beutel Goodman’s inflation estimate for the Shelter component of PCE (weight of 23.6%), as well as our estimate of the non-Shelter component of PCE (weight of 76.4%). Our estimate for the Shelter component of PCE uses market measures of house prices as a leading indicator of future expectations of month-over-month Shelter Price Index growth. Our estimates for non-Shelter components are based on month-over-month growth in non-Shelter core inflation of 0.15% for the “low” scenario; 0.25% for the “medium” scenario; and 0.35% for the “high” scenario. Estimates are as at January 31, 2023.

| U.S. Core Prices Scenario Table | ||||

| Historical Data | ||||

| Consumer Price Index, Shelter | Core Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index | |||

| 3M Avg | 0.73% | 0.30% | ||

| 6M Avg | 0.70% | 0.36% | ||

| US Core PCE Scenarios & Assumptions (M/M) | ||||

| Shelter Component* | US Core PCE Scenarios | |||

| Low | Med | High | ||

| Path to 0% by Sept 2023, BG estimates based on Market indicators | Non-shelter component at 0.15% MoM | Non-shelter component at 0.25% MoM | Non-shelter component at 0.35% MoM | |

| 2023 Jan | 0.62% | 0.26% | 0.34% | 0.41% |

| 2023 Feb | 0.54% | 0.24% | 0.32% | 0.40% |

| 2023 Mar | 0.47% | 0.22% | 0.30% | 0.38% |

| 2023 Apr | 0.39% | 0.21% | 0.28% | 0.36% |

| 2023 May | 0.31% | 0.19% | 0.26% | 0.34% |

| 2023 Jun | 0.23% | 0.17% | 0.25% | 0.32% |

| 2023 Jul | 0.16% | 0.15% | 0.23% | 0.30% |

| 2023 Aug | 0.08% | 0.13% | 0.21% | 0.29% |

| 2023 Sep | 0.00% | 0.11% | 0.19% | 0.27% |

| 2023 Oct | 0.00% | 0.11% | 0.19% | 0.27% |

| 2023 Nov | 0.00% | 0.11% | 0.19% | 0.27% |

| 2023 Dec | 0.00% | 0.11% | 0.19% | 0.27% |

*Weight of shelter component in PCE is approx. 23.6%; The three-month and six-month averages are based on Shelter component of CPI; historical data as at January 31, 2023

Lessons from the Past on Monetary Policy

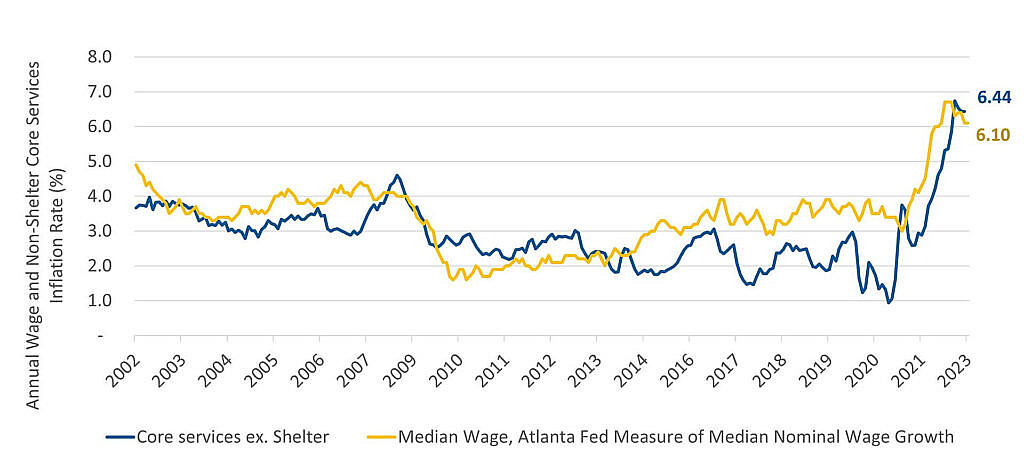

In its Q4/2022 Monetary Policy Report, the BoC stated that “excess demand” remains a problem in the labour market. Unemployment remains historically low at 5% (3.5% in the U.S.) and many businesses are struggling to fill positions. This supply-demand disparity has in turn led to wage inflation, particularly in the Services sector.

In its report, the BoC pointed out that while wage inflation slowed somewhat in December, there is a long road ahead on that front: “With the pace of wage growth no longer increasing, the risk of a wage-price spiral has declined. However, unless a surprisingly strong pickup in productivity growth occurs, sustained 4% to 5% wage growth is not consistent with achieving the 2% inflation target.”

More so than any other factor, we believe that wages are the largest concern for central banks right now.

Exhibit 4: Wages & Non-Shelter Core Inflation. Wages are a key driver of Core Services ex. Shelter Inflation and as the graph shows, both have experienced a significant spike since 2021.

Source: Beutel Goodman, Macrobond, Bloomberg L.P., as at January 31, 2023

No Easy Answers

Job losses are a harsh medicine for an overheated economy, but are likely necessary to bring down the stickier parts of core inflation. Core inflation has held steady around 5% since the middle of 2022, but it is expected that Shelter prices will come down as house prices fall — this should bring core inflation down from 5% to closer to 3.5%. To get to the 2% target, however, will likely require wages to come down.

Inflation has dominated headlines over the past year and that will likely be the case for some time yet. Bond markets are pricing in a rate cut of 100 basis points by the end of 2023, but central bankers have been messaging that this won’t be the case. The implied interest-rate forecast by the bond market means investors are expecting one or more events to occur that require central banks to ease:

- The tightening cycle triggers an asset bubble bursting, which requires an immediate change in course from central banks;

- The economic slowdown is more severe than central banks are forecasting; and/or

- Inflation rapidly descends to the 2% target and central banks declare victory.

None of these scenarios are our base case. Rather, we believe that the Bank of Canada will likely pause interest rate hikes for the remainder of 2023, while the U.S. Federal Reserve will also pause – but after one or two more hikes. For that reason, we believe it is better for investors to prepare for many different outcomes, including a prolonged battle with inflation.

[1] “Sticky-Price CPI”, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, https://www.atlantafed.org/research/inflationproject/stickyprice

Download PDF

Related Topics and Links of Interest:

- The Return of Income

- This Time is Different: No Monetary Safety Net for Markets in 2023

- The Risky Business of a Hiking Cycle

- Beutel Goodman Core Plus Bond Fund

©2023 Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd. Do not sell or modify this document without the prior written consent of Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd. This commentary represents the views of Beutel, Goodman & Company Ltd. as at the date indicated.

This document is not intended, and should not be relied upon, to provide legal, financial, accounting, tax, investment or other advice.

Certain portions of this report may contain forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements include statements that are predictive in nature, that depend upon or refer to future events or conditions, or that include words such as “expects”, “anticipates”, “intends”, “plans”, “believes”, “estimates” and other similar forward-looking expressions. In addition, any statement that may be made concerning future performance, strategies or prospects, and possible future action, is also forward-looking statement. Forward-looking statements are based on current expectations and forecasts about future events and are inherently subject to, among other things, risks, uncertainties and assumptions which could cause actual events, results, performance or prospects to be incorrect or to differ materially from those expressed in, or implied by, these forward-looking statements.

These risks, uncertainties and assumptions include, but are not limited to, general economic, political and market factors, domestic and international, interest and foreign exchange rates, equity and capital markets, business competition, technological change, changes in government regulations, unexpected judicial or regulatory proceedings, and catastrophic events. This list of important factors is not exhaustive. Please consider these and other factors carefully before making any investment decisions and avoid placing undue reliance on forward-looking statements Beutel Goodman has no specific intention of updating any forward-looking statements whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise.